After going missing for three weeks in 2000, Petie Chalifoux’s grandmother was found deep in the forest of her home territory.

Her body was located near her vehicle, three hours off the main highway leading to her northern Alberta community.

One theory was that 72-year-old Angeline Willier, a member of the Driftpile Cree Nation, had gotten lost, that she had driven down a dirt road and become disoriented before her death, but that was a possibility her family just couldn’t accept.

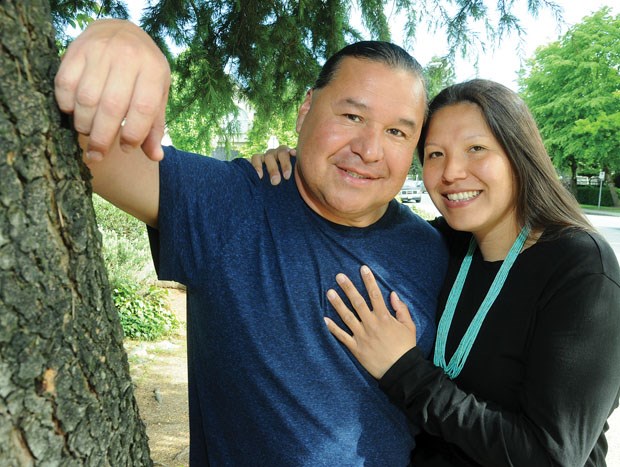

“She knows that backcountry,” says Micheal Auger, Chalifoux’s longtime partner in life and in filmmaking, explaining Willier grew up on that land and had spent countless hours there over the course of her life.

Chalifoux’s family visited the site, heightening their suspicions that foul play had occurred. Some of Willier’s belongings were found scattered throughout the woods, including her keys, but other items were strangely missing, like her wallet and identification cards, as well as her walker, which she had been dependent on at the time due to a broken leg.

Willier’s case, once closed, has recently been reopened and investigators are continuing to search for answers surrounding the mysterious death of the senior.

The event thrust Chalifoux into the harsh reality faced by all too many Canadian families affected by missing and murdered indigenous women and girls.

Wanting to take action to prevent others from experiencing similar tragedies and stop violence against all women, Chalifoux, also a member of the Driftpile Cree Nation, and her partner Auger, a member of the Bigstone Cree Nation, have turned to their creative talents. Through film, the North Vancouver couple is aiming to contribute to the growing dialogue on how to make this a safer, better world for all, and are hard at work on their first feature film, River of Silence, a fictional tale chronicling one First Nations family’s journey when faced with the horror of losing a daughter.

“This is a story about a family and loss, and I believe – we hope – that anybody around the world could relate to that. At its core, that’s what it’s about. But it’s also about the fact that here in Canada there’s what we consider to be an epidemic over the last 30, 40, 50 years, this growing thing. And so now we’re saying enough’s enough. All kinds of people have been stepping up to say enough’s enough and we’re just adding our skill set, in terms of narrative storytelling on film, to echo and support the efforts,” says Auger, 51.

“Our goal is to open windows and doorways into deeper dialogue between all people because it isn’t just native and white on the opposite sides of things. … You can’t force people to understand so we’re trying to use the creative skills and tools and opportunities that we have to say, ‘Hey, here’s something you might want to consider,’ but present it in a beautiful way,” he adds.

Finding her voice

Chalifoux, 32, had her own life path altered after surviving a vehicle accident in 2013.

“I feel like that really shifted my mentality because in that instant it was like I could have been dead,” she says.

In addition to filmmaking, Chalifoux is a renowned hoop dancer, regularly travelling within Canada and internationally to perform. She was returning home from a show in Merritt one early morning when the Greyhound bus she was a passenger on was involved in a 17-vehicle crash on the Vedder Canal Bridge in Chilliwack.

The bus rear-ended a pickup, and Chalifoux sat frozen in her seat as the truck’s rear end raised up until she could see its tail lights. She braced for impact, convinced it was going to come straight through the window to where she sat at the front of the bus.

Luckily, the truck settled back down, its bed subsequently flattened into a pile of wreckage.

“It looked like a Smart car by the time it was done. None of us could get out, we had to wait for the Jaws to come,” she says.

The crash gave Chalifoux a concussion as well as injuries to her neck, back and knee.

Since her grandmother’s death 16 years ago, she had wanted to take action in her honour, but something always stopped her. After the bus accident, however, everything changed.

“It was seriously that point in my life where I realized I was living in so much fear and there’s nothing to be afraid of. If we want to create a better world for ourselves, for our home, our people, and then of course the people we interact with, we need to make a big change in the environment that we live in and of course in the world. I feel like this film, River of Silence, will be that change, it will change the aspect of people’s minds. River of Silence is not a film for indigenous people because it’s a film that shows the experience that a lot of indigenous people are having currently. We hope to reach everybody else who has not experienced this and has no idea the pain that we go through, we being people who’ve lost somebody to such a tragic circumstance,” she says.

Chalifoux is currently a student in Capilano University’s bachelor of motion picture arts program and is set to graduate in the fall.

Through her studies she gained an interest in screenwriting. The seeds for a story were planted in the wake of her grandmother’s passing, and she spent a year and a half carving out the River of Silence script.

The writing process proved cathartic.

“There was a lot of grieving because of my own family’s story and then also researching other stories across Canada. So many people have gone through this. Combining all these different elements to make River of Silence, it definitely helped me to release a lot of the pain that I didn’t know I had. I was stuffed for 15 years,” she says.

With a screenplay in hand, Chalifoux called upon her partner to direct. Auger graduated from the master of digital media program at the Centre for Digital Media in 2013 and has long had a passion for narrative filmmaking. He’s done a little bit of everything over the years, including television news reporting and documentary production, as well as corporate work focused on indigenous topics and issues.

“While we’ve been building towards a feature film … over the last 10 years, we were honing our craft and developing our skill sets, but also serving Aboriginal communities and organizations because we feel like filmmaking, video, the arts that we do, are in service of making things better for our people, but really for the world too,” he says.

While River of Silence marks their first feature film, the couple has collaborated on a number of projects over the years, most recently a short film entitled The Shifter, which was released in November 2015 and screened at the San Francisco American Indian and LA Skins film festivals. Chalifoux served as writer and producer, as well as contributed some visual effects, and Auger filled the roles of director and producer.

The Shifter is about a young woman who is attacked.

“Through rape her inner voice is awoken and it’s symbolized through the ability to shape-shift into different animals,” says Chalifoux. “I guess it’s like reclaiming your power and finding your voice in a modern context.”

That theme was among those expanded upon in River of Silence. In addition to their screenwriting and directing roles, Chalifoux and Auger, respectively, are producing the work through their company, Sohkeciwan Productions. They’re grateful for funding received under Telefilm Canada’s Micro-Budget Production Program and for Capilano University, which is providing production equipment, consultation and post-production support. They’re also grateful for the support of a variety of other donors.

When asked what it’s like to work with her partner on the film, Chalifoux says it’s something they thoroughly enjoy.

“I feel like we have our own communication level without words. Across the room, looking at each other, a quick nod, OK, we know what we need to do, we’re onto it. Other times there’s something so frustrating we need to go out and walk. We get together and we go for walks just out here in Mosquito Creek, so really using the land a lot to help to get the breathing space when times get tough. But yet we still do it together. I think we’re finding a really good balance between work and personal life,” she says.

Empowered plot

“This is about a family that loses their daughter,” says Auger.

The plot of River of Silence follows Helen Wolf (played by Mariel Belanger), a successful art gallery owner, and her husband Nathan (Stan Isadore), a lawyer, living in present-day Vancouver. The couple is an example of what’s referred to as “living in two worlds.”

“As indigenous people, most of us grew up on the land but we moved to the cities to go to school, to find ways to function and still be healthy in the modern world – education, jobs,” says Auger.

Originally from a fictional northern community called Buffalo Mountain, Helen and Nathan have a 24-year-old daughter named Tanis, played by Roseanne Supernault.

“When we meet them, Tanis has just finished her spring semester at university and is anxious to go back home to their reserve, to their home community, to visit and spend time with extended family, particularly her grandmother Margaret. But unfortunately she doesn’t make it, she does not arrive and that’s what triggers our story,” says Auger.

A search for Tanis ensues, leading to the eventual discovery of her body.

“That again changes everything to they’re now another family with a girl who’s gone missing and was found murdered,” he says.

The remainder of the film follows the impact of the news on the couple, both individually and as a unit, as they try to cope and come to terms with what has happened and find a way through the darkness and sorrow. That dark material brought out brilliant performances in her actors, says Auger.

“Stan and Mariel, Roseanne, what they’re bringing in their performance is just nothing short of spectacular in my opinion,” he says. “These are people who know and who are very much connected to the pain and the suffering that this family goes through.”

Stan Isadore, an Alberta resident and member of the Driftpile Cree Nation, is playing the role of Nathan, a father whose life is turned upside down when his daughter goes missing.

Isadore, who serves as a councillor for his Nation in addition to pursuing acting (recent credits include multiple seasons on TV series Blackstone), was strongly attracted to the River of Silence script, finding it refreshing in its portrayal of First Nations people, all too often characterized onscreen in a negative light.

“This film, it brings out the reality of what’s happening to murdered and missing First Nations women,” he says. “It talks about the reality of what they’re going through. We also have to remember that it identifies the mom and the dad as hard-working, devoted, loving parents whereas a lot of First Nations films don’t really acknowledge or recognize that. There’s a lot of First Nations men and women out there who are very devoted, who live in cities, who live in towns, have big, beautiful homes and vehicles and everything that their kids need. They’re just not portrayed in stories like this. This is one of the first where you have a First Nations family who is making it in society, and who’s in the mainstream and making a very honest, good living, and then this happens. As opposed to another film where they’ll portray a First Nations family struggling on a reserve. This is very different.”

A father himself, Isadore was particularly drawn to the emotional journey his onscreen counterpart is forced to endure.

“Reading the script and identifying myself with the character, for me it wasn’t much of a challenge, it wasn’t very difficult,” he says. “I have an eight-year-old son and like many fathers and many mothers out there, he’s my world. He’s always first no matter what.”

Isadore travelled to B.C. for the tight River of Silence filming schedule, which occurred from April 16 to May 3. Locations included two different homes in North Vancouver as well as Presentation House Gallery, the Vancouver Aboriginal Friendship Centre, and in the woods on the Nooaitch First Nations territory west of Merritt.

Chalifoux and Auger are pleased with the efforts of their cast and crew, a number of whom are students and recent graduates of Capilano University (from both the motion picture arts and the indigenous independent digital filmmaking programs), as well as North Shore residents, grateful for their dedication to the project.

Another strong supporter of the project as well as cast member is Duane Howard, a longtime friend of the couple’s, who has been part of River of Silence from the beginning. Howard, who plays the role of Trevor, Helen’s brother, was recently featured as Elk Dog in the Academy Award-winning production The Revenant alongside Leonardo DiCaprio.

The cast and crew are grateful for the support of their fearless leaders, Chalifoux and Auger.

“Watching them work – it’s the passion, the devotion, the dedication from beginning until now that they’ve expressed and that they show while they’re on set, while they’re off set. They’re taking this as their first-born baby and giving it everything that it requires to grow,” says Isadore.

They hope to have the film completed by the fall.

A way to remember

Chalifoux had a close relationship with her late grandmother, a strong, dynamic and independent woman. She hopes that River of Silence prevents Willier from being forgotten, like many other missing and murdered indigenous women and girls.

“For me, this is a good way to remember,” she says.

When asked about the significance of the film’s title, the couple explains it’s a mixed metaphor. Water is a very healing element for indigenous people, it’s the breath of life for the earth and for the people who live on it. They chose the word silence because it refers to the moment when character Tanis’ life is extinguished forever by the river.

In contrast, it’s important to note that a river is not silent.

“The title represents the roar and the growing voice of indigenous people and for us it’s through film, it’s through visual arts,” says Chalifoux.

For more information, visit rosthemovie.com.