Under a movable shelter several storeys high at Seaspan Shipyards, the graceful curve of a ship’s bow arcs upwards, dwarfing the hard-hatted workers who stand on the yard below.

Near the bottom of the ship, dark circular tunnels hold bow thrusters that will set below the waterline. Above, workers stand on what will eventually be one deck level of the Sir John Franklin, the first of three Coast Guard offshore fisheries science vessels under construction at Seaspan in North Vancouver.

Soon, “Big Blue,” Seaspan’s massive $18-million gantry crane, will hoist another massive piece of the ship on top of this one to be fit together, like a giant piece of Lego.

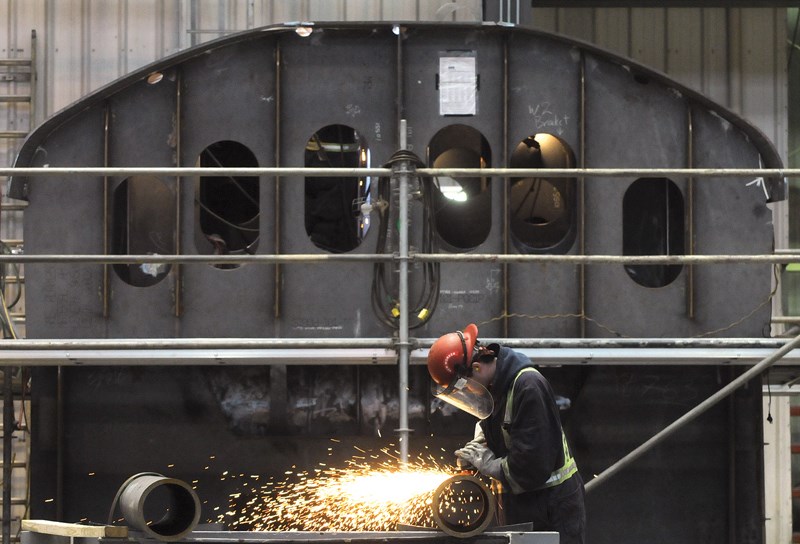

A similar assembly process is underway nearby for the stern of the ship, where a worker on a scissor lift grinds a seam that will join two huge sections of the ship together.

Brian Carter, Seaspan’s president of shipyards, stands below the very back of the vessel, pointing out where the rudder will eventually sit, and where rounded edges will accommodate a fisheries net that will be used to do assessments of fish stocks.

Tracking how the pieces of the ship – known as “blocks” – come together here is one of the crucial markers of how work on the first of the federal vessels built under the National Shipbuilding Strategy is going.

“If that stays on track we’re generally on track,” says Carter. “You can’t fake that. You can’t hide it or mess around with numbers to make it look OK. You either did it or you didn’t do it.”

These days, workers at Seaspan are building ships in a very modern way, in a process that is more like a manufacturing plant than the shipyard building of the past. In 2014 the shipyard completed a two-year $155-million modernization process with expert advice from a large Korean shipyard, putting Seaspan in the company of other large shipyards around the globe.

Rather than build the hull of the vessel first, the ships are built in blocks, measuring about 12 metres by 12 metres each. The three offshore fisheries vessels are each made up of 37 blocks, which are joined together into nine final “grand blocks” that form the ship. Today, all 37 of the blocks for the first ship have either been built or are under construction, and the ship is 50 per cent complete. Nineteen of the blocks for the second ship are also under construction.

Welding supervisor Surjit Parmar, 67, is one of a handful of employees who has worked at the shipyard on the North Shore for more than 40 years. Over those years, “I’ve seen a lot of changes,” he says. Back in the boom-or-bust days of the industry, “They’re busy, they’re not. They’re busy, they’re not,” he says.

Seaspan’s modernized yard is a point of pride for Parmar. “This shipyard is one of the best in North America,” he says. “We can compete with anybody in the world now.”

Winning the bid to become the federal non-combat shipbuilder under the National Shipbuilding Strategy five years ago has been a game changer for Seaspan. An umbrella agreement worth up to $8 billion gave the shipyard the right to negotiate contracts for construction of up to 17 vessels, including three 63-metre fisheries vessels, an 86-metre oceanographic science vessel, two 174-metre Navy joint support ships, a 150-metre polar icebreaker and up to 10 smaller vessels. Those contracts are expected to provide the shipyard up to 15 years of work.

The process hasn’t been without its challenges.

The contract to build the first three fisheries vessels – budgeted at $687 million including operational servicing of the ships and including up to $514 million for construction – came in almost three times the original budget of $244 million. But the original budget figure, set in 2007 and never updated, didn’t contain provision for inflation, project management, engineering, design or contingency costs.

Seaspan cut the steel for the first fisheries vessel in June 2015, at a milestone marked with celebratory political speeches.

Since then, there’s been a learning curve as construction of the first ship has progressed. That’s not unexpected, says Carter.

“Shipbuilding like this hasn’t happened in Canada ever. It’s all new,” he says.

Part of the learning is “getting to know how fast we can do the work in the facility,” he says. “You can do a lot of work to guess what that will be. But it’s doing the work that tells you what the facility is truly capable of.”

“It hasn’t been perfect and we didn’t expect it to be perfect,” he says.

Early on in the process, in December 2015, the federal government assessed the shipyard as being 13 weeks behind on a 93-week construction schedule for the first vessel. Things have changed since then, although neither the federal government nor Seaspan provided information about whether vessel construction is now considered on time.

Seaspan tracks every stage in the shipbuilding – how long it takes to fabricate a steel panel, how long it takes to install pipes – in detail, as does the federal government.

As owner’s representatives, half a dozen Coast Guard personnel are among the team of project managers overseeing the construction of the fisheries vessels.

Navy personnel who live and work in North Vancouver are also part of the Seaspan team now working on the design for the massive joint support ships.

Senior officials from the defence department and Coast Guard also pay regular visits to the shipyard from Ottawa. “They want to see how we’re doing first hand,” says Carter. As a relative newcomer to Canada from the U.S. himself, Carter says, “There’s a lot of stewardship of the taxpayer dollar here. They do a good job of making sure we’re delivering value to government.”

The first ship is expected to be in the water by June 2017 and delivered to the government by the fall of 2017. Construction of the second fisheries vessel started this year at the end of March and is expected to be ready six months after the first ship is delivered.

So while the first ship enters the final stages of production, steel for the second ship is simultaneously being cut and welded into panels in the shipyard’s panel shop. The panel shop is home to some of the more recognizable modernizations, such as the automatic welder which can sweep through a panel in one pass, fusing large pieces of steel with multiple welding heads.

“We can do this work in about 10 per cent of the time that we used to,” says Carter. “It probably took about 40 people out of this process and got them into more complex work.”

Steel is cut on a plasma cutting table that downloads an electronic CAD file and cuts it accurately to within millimetres. When work on multiple ships is fully up and running, steel is expected to run continuously through this panel assembly line.

Work on a third offshore fisheries vessel is expected to begin later this month. Under the new system, up to four vessels can be built at the yard at one time, says Carter.

Next door, in the forming shop, is where some of the more complicated work is done – turning flat pieces of cut steel into the distinctive curved lines that make up a ship. The centrepiece of the shop is a new 1,000-tonne hydraulic plate press, used to bend thick pieces of steel into complex curves. “This will be able to form the polar icebreaker, which is up to two inches thick in places,” says Carter. Four highly skilled employees are operators of the press. Making sure their skills are passed on to younger workers is a priority. “This is where the artisan work happens,” he adds.

Further down the production line, in the block assembly shop, those curved and straight steel panels are put together into three-dimensional pieces of the ship.

Here, a huge cylindrical propeller shaft tunnel sits supported on a metal frame, to be welded into a section of the bow for the second vessel.

A short distance across the yard, more complicated systems – from electrical systems to plumbing – get added to the blocks.

Here, ventilation ducting and cable trays are visible in a section of what will become a part of the bridge on the Sir John Franklin.

Most of the work inside the ship, such as the heating and ventilation system being installed now, is done by a number of subcontractors, who design, source and install those systems. Collectively that work is significant. According to a 2013 report from the parliamentary budget officer, those subcontracted systems can make up more than half of a ship’s total value.

Seaspan’s suppliers on the non-combat ships range from Ideal Welders Ltd. in Delta, a pipe and pressure value supplier, on the smaller end, to Thales Canada Inc., the Canadian arm of a multinational company that specializes in aerospace and marine defence systems on the larger end. Genoa Design International Ltd., a company based in Atlantic Canada that uses technology to extract design specifications from 3D models, is another subcontractor.

Canadian arms of multinational companies including Alion, Computer Sciences Canada Inc. and Vard Marine Inc. are among the other suppliers.

In cases where software and electronics must be sourced from other countries, terms of the federal government’s contract require those contractors to spend an amount equal to that value in Canada – although not necessarily on the shipbuilding project.

Following the fisheries ships, Seaspan is scheduled to begin work on a larger oceanographic science ship. An engineering contract for that has been signed and contracts worth more than $65 million to source parts requiring a long lead time, like propulsion systems, for both the science and joint support ships were signed in March of this year.

A construction contract for the oceanographic vessel – originally targeted for this year – is now expected in 2017, as is the contract to build the joint support ships.

Likely the biggest political issue for the shipbuilding strategy, however, concerns the project budgets, formulated up to a decade ago. Critics including a former auditor general and parliamentary budget officer have pointed to those figures – including approximately $144 million for the ocean science ship – as underestimated.

An auditor general’s report in 2013 flagged the $2.6-billion budget for the two joint support ships as unlikely, pointing out the Navy had already been forced to drop the number of support ships from three to two to fit the budget and suggesting a figure between $3 billion and $4 billion as more realistic.

An update on those projects – including anticipated timelines and budgets for the National Shipbuilding Strategy overall – is expected by the end of this year. The federal government did not respond to requests for updated information by press time.

One large challenge facing Seaspan now is the need to start beefing up its skilled labour force to take on the larger shipbuilding projects expected in the next few years. This week, the shipyard passed a milestone of hiring the 500th tradesperson to work in the yard – up from 150 just a few short years ago. The shipyard currently has 46 apprentices in training, and hopes to hire at least a dozen more by the beginning of 2017. It’s anticipated, however, that Seaspan will need to double that by the time work on the joint support ships gets underway in a couple of years.

Carter is confident the North Vancouver shipyard can meet that goal. The work is well-paying (tradespeople earn an average wage of about $40 per hour plus benefits), and unlike work in some sectors, like the oil and gas industry in more remote parts of B.C. and Alberta, the shipyards present a chance for workers to be home with their families.

Blake Crome, 32, is an apprentice welder at Seaspan who understands that appeal. “I knew it was going to give me the opportunity to stay local with my work,” he says. “It’s a good wage and it’s nice to go home every day.”

Not surprisingly, the politics that has always surrounded the awarding of large shipbuilding contracts in Canada hasn’t let up in the five years since Seaspan won the bid to build the non-combat vessels.

Shipyards like Davie in Quebec have repeatedly suggested that in order to meet its deadlines, Ottawa should parcel out more of the work to other companies. Earlier this year, Davie raised eyebrows by submitting an unsolicited bid on some of the work already awarded to Seaspan under the National Shipbuilding Strategy.

Top brass at Seaspan say that isn’t phasing them, adding they’ve received good support from the new Liberal government in Ottawa.

“There are companies out there that lost the competition that would love to see it broken up,” says Carter, adding, “We’re Canada’s non-combat shipbuilder. It’s very clear. There’s sometimes noise out there every once in a while but it’s just that. It’s just noise. We don’t get too worked up over that.”

His priority is getting that first ship – and all the others after it – in the water.

Parmar, who has built barges, tugs, a commercial ice breaker and a ferry during his four decades in North Vancouver shipbuilding, wants to see that as well.

“This is where I started my career. This is where I’m going to end it,” he says. “I want to see the ship floating.”