Summer was here and the harvest was in.

Idling at the fence that runs along the first base line at Viewlynn Park, Marc Rouleau felt it.

Just a few days earlier the 11 year old pegged a line drive up the middle during a tryout for the Lynn Valley Little League all-stars.

It wasn’t the hardest shot he’d ever hit, but it got him on base. And more importantly, it got him on the team.

The team.

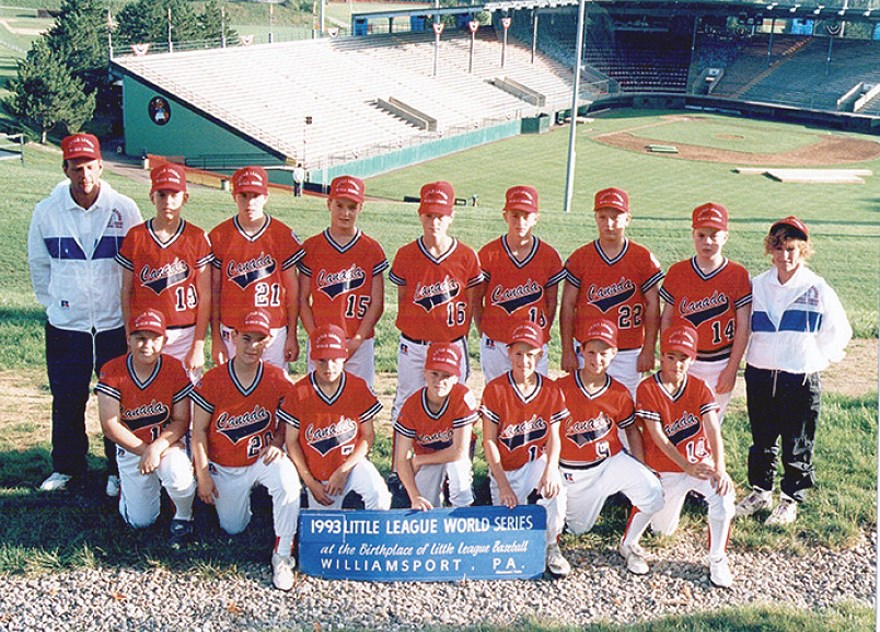

Rouleau had watched the Little League World Series on TV every year and some part of him knew that this team – with overpowering pitching and lightning gloves – was good enough to make the trip to the show in Williamsport, Pennsylvania.

“I told (Shaun Layton’s) older brother . . . I said, ‘We’re going to the World Series.’”

Top of the first: Getting there

“It’s the beginning of the summer and I’m standing in the lobby of a thousand-story grand hotel, where a bank of elevators a mile long and an endless red row of monkey attendants in gold braid wait to carry me up, up, up. . . .’’ – Michael Chabon, The Mysteries of Pittsburgh

Not since Eve threw the first curve to Adam had any North Shore team packed their bags for Pennsylvania. But coach Eden Briscoe had watched this group evolve from toppling T-ball stands to pulling pitches to the opposite field. By 1993, there was enough talent at Viewlynn to win the division. Heck, they might even get all the way to the B.C. championships in Whalley.

“Four years ago, I knew this team would contend for the provincials,” Briscoe told the North Shore News that summer.

But assembling the all-stars meant picking 13 kids from a pool of 10, coach Kathy Barnard says.

The team was young and looked their age.

As opposed to the infamous little leaguers who sport five o’clock shadow after six innings, the Lynn Valley players resembled kids who might deliver your newspaper if their big brother had the flu.

But what they lacked in age they made up for in versatility.

The kids played soccer and hockey. And between pitches and rinks and diamonds – playing with and against each other – they’d formed a bond, Shaun Layton explains.

“We all knew that we’d be playing together later . . . like the World Cup,” he offers.

It’s like this: Manchester United and Liverpool might share a “you-have-have-filled-my-tea-with-lumps-of-sugar” type of hatred while in England; but abroad they were teammates. Countrymen.

So it was with the Lynn Valley kids. When school was out they were an elite squad assembled to achieve a single goal – although not everyone knew what that was.

“I didn’t really have a clue that there was a Little League World Series,” first basemen Scott Carlson recalls, adding that he remembered hearing something about: “this place called Williamsport.”

For some of the players, the Little League World Series was a myth, one of those rumours that populates your imagination at 12 years old, like the alligators in the sewer or the school principal’s social life. It wasn’t about Williamsport, anyway. It was about baseball.

“You just remember that feeling of summer starting,” Spencer Barnard says.

“We were just a bunch of friends playing baseball in the summer without much other worries or cares,” Carlson agrees.

They practised twice a day, Layton recalls. It was tough, but then again, there was only so much Mortal Kombat II you could play.

“We didn’t overwork them,” Barnard says.

They never had a batting cage, she says. They didn’t push pitchers to throw those elbow-taxing curveballs that nudge orthopedic surgeons into higher and higher tax brackets.

But Rouleau remembers Huffy and Norco bikes rolling to Viewlynn where they played and watched and talked about the game.

“We lived baseball,” he says. “We just ate it up.”

They’d spend hours playing American ping pong, a slow-pitch baseball drill with two rows fielders and a few elastic rules everyone knows but no one remembers. The game was great practise for the most unteachable element of baseball: guesswork.

Negro league legend Cool Papa Bell used to tout the importance of: “the nuances that are the ambrosia of baseball,” according to writer Mark Kram.

“That’s how we beat big league teams. Not that we had the best men, but we outguessed them,” Bell told Kram. “There’s a lot of unwritten baseball, you know.”

A good centerfielder tends to stand a hair to the right or left of the pitcher, studying the batter for some twitch of the toes or shift of the shoulder that offers a clue to where that ball’s going.

As for where Lynn Valley was going, well, that was tougher to guess.

Williamsport “wasn’t in the plans,” Layton says. After all, beating Whalley was “a task in itself.”

Whalley, Quebec and the Man-Children

The rumour, Layton remembers, is that Whalley already had tickets for the Canadian championships.

“Back then, it seemed like a team from Whalley was going either every year or every other year,” Lentsch says.

Whalley had experience, good coaching and home field advantage.

But for four straight games, Lynn Valley pitchers Lloyd Haggard and Clint Hosford threw hard, accurate pitches, the kind of stuff broadcaster Tim McCarver used to call Linda Ronstadt. (As in: “Blue Bayou,” or: “blew by you!”)

Haggard threw a one-hitter. Hosford did him exactly one better, throwing a no-hitter. And with the team committing just two errors in four games and Blake Anderson pursuing pop flies to walls and warm-up mounds, the team topped Whalley 4-1.

For the first time in 22 years, a North Shore team headed to the national stage.

“I’m ecstatic,” Briscoe told the North Shore News.

For a lot of the players, the win meant taking their first look at the world outside B.C.

“It was kind of a life trip,” Lentsch remembers.

And as flustered parents made apologies and promises to their bosses, the team got ready for Quebec.

“They were like man-children,” Rouleau recalls.

The Quebec team were the defending Canadian champs. And in their first game against Lynn Valley one of their power hitters sent a line drive into Haggard’s chest.

The kid collapsed on the field before being taken to hospital. He was released later that day.

Thinking about that summer 25 years ago, the Lynn Valley players have different and sometimes contradictory memories. Lentsch remembers cajoling his somewhat strict father to please, please, please let him get LV shaved into his head. “He finally allowed it but it was on a one-time basis, that’s for sure,” he laughs.

Layton has no memory of anyone shaving LV into the side of their heads.

Some players remember a crucial triple that won them the game while others are sure it was a home run.

But everybody remembers Haggard getting the out at first base and then dropping.

“I remember that game vividly, 25 years later,” Spencer says.

Lynn Valley lost that first game but the round robin offered them another shot at Quebec in the finals.

If there was one game that summer when, as baseball scribe Red Smith once put it: “malice lay over everything, thick as mustard on a frankfurter,” it was that final against Quebec.

“We kind of had a rivalry with them,” Layton says, remembering the sound of a Quebec fan honking a car horn from the stands. “No one really liked their fans.”

Lynn Valley scored one run early but their lead felt fragile as a sandcastle in a high tide.

Barnard remembers watching Hosford’s control slip just a little as the game wore on.

Should they treat him like a loose tooth and yank?

Briscoe shook his head.

He had “absolute faith” in Hosford.

The game stayed tight until Haggard laced a home run in the fifth inning.

Lynn Valley took the game and the championship 2-1 after Hosford got Valleyfield’s last batter on strikes.

“That final strikeout,” Spencer reminisces. “I remember it like it was yesterday.”

In his book The Great American Novel, Philip Roth wrote that were two kinds of baseball. “There is by the book, the way you do it. . . . But then there is by hook and crook, by raw guts and all the heart you got.”

Lynn Valley played the second way.

They were hoping to make history in Williamsport – unaware they’d already made it.

The first woman in Williamsport

Branch Rickey, the manager of the old Brooklyn Dodgers, wasn’t trying to integrate Major League Baseball when he signed Jackie Robinson in 1945 – or at least, that’s what he told people.

But the truth, according to Red Smith, was that Rickey deplored racism; that he’d wanted to pop Jim Crow since the days when the Wright brothers were wondering if that thing in their barn would fly.

But to bust that line separating black from white, Rickey had to say it was all about baseball. He had to say he didn’t care if ballplayers were purple or green so long as they could play ball.

Kathy Barnard, on the other hand, really didn’t care if ballplayers were purple or green.

As a kid growing up in Powell River, Barnard was one of the few girls playing baseball against the boys, but it wasn’t a political statement.

“They didn’t have a girls league,” she says simply.

Her coaching career, which she calls “a fluke,” was born out of similar scarcity: her son’s team didn’t have a coach.

It was almost game time and the coaches were late – again.

With daylight disappearing the parents made a demand disguised as a question: “Maybe you could just warm the kids up, Kathy?”

So, she warmed them up. She joked, she chattered, she taught. And eventually, the other parents had enough, she recalls.

“The (coaches) are nice but they can’t come as often as you can and actually you play better ball . . . Would you mind coaching?” they asked.

Five years later, Barnard made history as the first woman to ever coach in the Little League World Series.

She laughs when she describes the Lynn Valley kids who blinked when they were asked about the milestone.

“Who?” they’d say, mystified. “Kathy?”

Purple or green – she was a baseball coach who could coach baseball.

But as different as she might be from Rickey, there’s a Brooklynese description that feels almost perfect for both of them: “A man of many facets – all turned on.”

Barnard was the good cop coach (“When (a kid) made an error and needed a little pat on the back they’d come my way,” she confides.). She was also a pal/mentor/trailblazer who even procured equipment from time to time.

She remembers telling the team’s story to her seatmate on the flight into Pennsylvania.

It was a magic summer so far, she’d told her new friend. Although, she explained, some of that magic splintered in New Brunswick.

“We had a magic Easton bat,” she says. “Unfortunately, we broke it.”

Her seatmate smiled.

“It’s your lucky day,” he told her.

He was a rep with the Easton Company and it just so happened he could get them the exact same model of bat.

The team was on the practice diamond when the Easton rep set foot on the grass like Shoeless Joe Jackson stepping out of an Iowa cornfield.

He had the bat.

Could I take the first swing, Barnard asked.

“It’s your second lucky day,” he told her. “I used to pitch Triple A.”

He chucked Barnard a fastball.

“I actually tagged it so hard . . . that I cracked my wedding band.”

Heartbreak, ping pong, and the way it was

The kid could eat.

In summer's last days the Lynn Valley team was staying at a dorm in Williamsport during the Little League World Series. Their neighbours were the defending champs from Long Beach, California led by pitcher and future major league ballplayer Sean Burroughs.

Marc Rouleau knew Burroughs was good. He’d heard the kid’s pitches pop like firecrackers when Burroughs warmed up. But it wasn’t until he saw him polish off four pieces of pizza, five ice cream sandwiches and two Cokes in the shared cafeteria that he was intimidated.

“This beast of a 12-year-old kid just putting back 3,000 calories like it was nothing,” Rouleau says.

It felt different in Williamsport, Lentsch remembers.

“All of a sudden, it kind of went from being a kid to being a professional ballplayer to a degree,” he says.

There were media scrums, adult meals and autograph hounds, Carlson recollects.

“That unfortunately hasn’t happened again in my life,” Carlson smiles. “I can walk the streets quite comfortably without people harassing me for autographs now.”

Under blue skies creaking with humidity, the team chased breaking pitches that beat their bats into the dirt as Panama thumped them 6-0.

The lopsided loss, however, had no impact on the pillowfights, indoor whiffle ball, and the nightly ping pong tournaments in the hotel

“We did the thing you’d figure 11 and 12 year olds do,” Cameron Janz laughs.

“Once we got to Williamsport, it was kind of playing with house money,” Layton explains. “We were just having a blast. No one, I don’t think, expected us to win the worlds.”

There were players from all over the world right beside them.

“You’re exposed to all these different cultures,” Andrew Janz says.

Following the rocky entry into pool play, Lynn Valley prepared to face a German team composed almost entirely of U.S. Air Force base kids.

After going hitless in the first game, Layton remembers his father urging him on.

“My dad was like: ‘You better get a hit,’” he laughs.

He did. It was the type of hit that Philip Roth would call a Lady Godiva: “meaning it had absolutely nothing on it at all.”

But it got him to first.

“I was pretty happy that I wasn’t going to go O for the World Series,” Layton laughs.

Playing under the lights for the first time, Lynn Valley pounded Germany 8-1.

The win set up a showdown with a Saipan and a chance to go to the semi-finals.

Lynn Valley led early but Saipan notched a dramatic comeback win in the bottom of the sixth and final inning.

“The coaches kicked themselves over that one,” Barnard says, remembering she and Briscoe discussing the right time to pull the pitcher.

She wouldn’t have minded giving the hook to a Toronto Blue Jay, Barnard says, but it’s different with kids.

“You never want to take that opportunity away from them, ever, ‘cause they’re never going to get it back.”

“It was . . . heartbreaking,” Layton says at first. But in talking about that game, Layton seems to catch himself and remember how much fun it all was. “I think I was more gutted when England lost the World Cup this year,” he adds.

“Loss is part of life,” Barnard says. “It’s over. You can’t take it back, you can’t do anything. It’s what it was.”

Extra innings

“Baseball memories are seductive, tempting us always toward sweetness and undercomplexity.” – Roger Angell, Game Time

Jurassic Park and Sleepless in Seattle were playing at Park and Tilford and the Esplanade 6.

The North Shore News published articles about West Vancouver’s slow growth rate and the District of North Vancouver’s plan to buy a gazebo just for smokers.

Lentsch remembers hanging around Hockey Cards Plus, his dad’s shop at Lynn Valley Road and Allan Road in those days.

“It was more a little kid’s area rather than a bank now, but they’ve taken over,” he says with a chuckle.

Lentsch, who now works as a firefighter out of Central Lonsdale, is one of the few players from that team who still lives in Lynn Valley.

“All that Lynn Valley ended up giving me as a kid, you end up being able to give a little bit back as well,” he says. “It’s kind of sad to see there’s only a couple of us left.”

Layton, who took his first plane ride that summer, is a seasoned traveller these days, flying to Spain four times in two years for “really fun R and D,” as he prepares to open his own tapas bar called Como Taperia in East Vancouver.

Cameron Janz is the CEO at Aqua-Guard Spill Response, a company charged with getting skimmers in the water and sucking up any oil spill. Rouleau, after playing some college baseball, teaches middle school in New Westminster.

“They’re not kids anymore,” Barnard reflects. “They’re as old as me; I don’t know how that happened.”

Barnard kept coaching. Coaching, she says, got her through the worst year of

her life.

She wasn’t planning to coach, of course, but when the actual coach didn’t show up . . . well, she found herself helming a girls baseball team called The Survivors. The name, inspired by the Destiny’s Child song, turned out to be apt.

Barnard was diagnosed with malignant melanoma that season.

The diagnosis, and the command to get her affairs in order, came just hours before the first pitch of a

Survivors game.

She told her family about the diagnosis. They cried. They consoled. And at some point in that first terrifying stage of grief, Barnard looked at her watch.

“Holy shit, I gotta go!” she called.

With a promise to talk about cancer later Barnard headed to the ballfield. It was her sanctuary. Her cancer-free zone.

“I did not get out of bed except to meet those kids at the ball diamond.”

Of course, the kids all found out. Barnard still remembers an eight-year-old named Victoria offering her a lawn chair and a few kind words.

Victoria, who had suffered through the same thing, told Barnard she’d lose her hair. She told Barnard she’d puke all the time. And she told Barnard she’d beat this.

She did. And she went on to found the Save Your Skin Foundation to advocate for other cancer patients.

She still sees the players from that ’93 team from time to time, she says.

“We criss-cross back and forth,” she says.

Lentsch coaches his eight-year-old son now. The kid wants to be a catcher, like his dad.

Lentsch was there for the Little League opening day ceremony this year.

Wayne Hobson, the longtime administrator for the district, asked if there was anyone there from that ’93 team.

“I was the only person,” Lentsch says.

A few weeks back, just as this year’s Lynn Valley team was entering the provincial tournament, Rouleau found himself on the Lynn Valley website.

“There’s nothing about our team,” he noticed.

He didn’t mind the season being over, so long as it wasn’t forgotten.

At the end of The Boys of Summer, Roger Kahn’s chornicle of the legendary Brooklyn Dodgers team of the early 1950s, Kahn heads to where Ebbets Field used to stand and finds himself seized by a question: “Sweet Moses, white or black, who will remember?” he writes.

But for the players who lived it, the summer of ‘93 is unforgettable.

“For most of us, that’s the only world championship of anything that we’re going to attend,” Carlson says. “It stays vivid in our memories.”

Barnard agrees.

“They gave me one of the greatest memories of my life.”