While most municipalities in the region are showing moderate population growth, West Vancouver is the fastest shrinking city in the Lower Mainland.

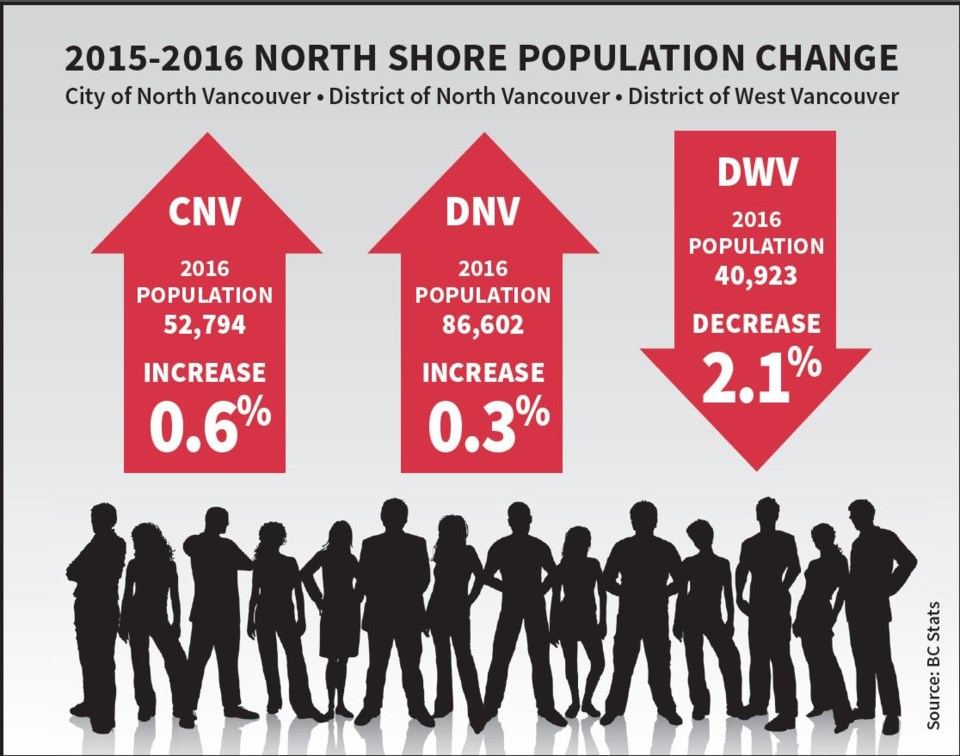

The province has released its annual population estimates, showing West Vancouver’s population fell 2.1 per cent in 2016. The City of North Vancouver and District of North Vancouver grew by 0.6 per cent and 0.3 per cent respectively, well below the average growth rate in Greater Vancouver, which was 1.6 per cent. All told, the North Shore experienced a small net loss in total population from 180,529 in 2015 to 180,319 in 2016.

West Vancouver’s population has fallen by 2,000 residents since 2011, a drop of 4.6 per cent. In that time, the District of North Vancouver has only added about 539 new residents, a growth of 0.6 per cent overall. Since 2011, the city has grown by 6.8 per cent. BC Stats calculates its estimates using the 2011 census as a baseline and factors in changes in vital statistics as well as BC Hydro and MSP registrations. New 2016 census data will be available in February.

West Vancouver Mayor Michael Smith said the numbers are troubling and a sign that West Van needs to change its attitude towards new development.

“We’re going to lose our young families. We’re going to lose our ability to hire young employees at the district and the school district and other employers in West Van,” he said. “The last policeman I swore in (as chairman of the West Vancouver police board) lives in Chilliwack. It’s a real problem.”

West Vancouver council has only approved one all-rental project in 40 years, Smith said, and downsizers are choosing places like Yaletown and North Vancouver where they have more options. But every new development proposal is met by community resistance and, sometimes, roadblocks at his own council.

“There’s a small but very vocal group that try to pretend that we’re rezoning properties all over the place, that development is out of control in West Van, and nothing could be further from the truth,” Smith said.

Andy Yan, director of SFU’s city program, said the numbers indicate which municipalities are doing the best at attracting working families, with cost likely being a major factor.

“I think it’s a function of housing, housing costs, employment and really where are the affordable and livable units versus where the jobs are?” he said.

By comparison, Langley, Surrey and Squamish grew by 3.3 per cent, 3.2 per cent and three per cent in the last year.

The types of new developments a council approves also makes a big difference, Yan said.

“What are the design arrangements? Are they studios? Are they three bedrooms?”

The low numbers may contradict popular perceptions that blame traffic on local residential development, a common complaint on the North Shore.

“That’s the funny thing about evidence,” Yan said.

But, Yan noted, population stats lack details on demographics like age, income and information on commuting habits. Those will be included in the next census data, which Yan is eagerly awaiting.

“Details matter. It isn’t just to blame things like development. It’s also understanding commuting patterns – how people are getting to work both on the North Shore and out of the North Shore. These numbers have both positive and negative implications.”

For all the headaches it causes, traffic is also an indicator of economic vibrancy, Yan added.

“Look at the other side of it. Would you rather have no traffic but less economic vibrancy?”

District of North Vancouver Mayor Richard Walton said he was not surprised by the 0.3 per cent growth, even though much of his council’s time is spent debating whether the district is growing too fast.

“I know we’ve got some concerns in the community that growth is out of control. What the number says to us is growth isn’t out of control. Our growth continues to lag behind the rest of Metro Vancouver,” he said.

The district is currently doing an review of its OCP, which will benefit greatly from next month’s census results, Walton said, particularly as it relates to current traffic problems. It may be the challenge is a lack of residential development, not too much of it, he said.

“If the traffic continues to grow noticeably and our population shows really an immaterial increase, then obviously there are other things going on in our community that straight population statistics aren’t telling the whole story,” he said. “It could even be an increasing number of our firefighters and teachers and hospital workers who are not able to afford to live here and therefore, we have an increasing commuter population here. They’d love to live on the North Shore and can’t because there’s not adequate housing.”

City of North Vancouver Mayor Darrell Mussatto said the 0.6 per cent growth the province estimated for his municipality seemed a bit low, although Yan said he was confident in the province’s methodology.

“Everybody says we’re going too fast. They’re mistaken because 0.6 per cent growth is very low,” Mussatto said.