Roddy MacKenzie still remembers the day when he was 11 and his dad burst out of the front door of their Calgary home, telling him to get in the car. The year was 1961 and his dad had heard a Lancaster airplane was approaching.

They sped up to Nose Hill, a high point overlooking the city, and watched through binoculars as the Lancaster approached.

“He watched that plane with incredible intensity,” said MacKenzie. “That was the last time he ever saw a Lancaster in the air.”

MacKenzie’s father Roland MacKenzie was a Canadian pilot in the Royal Air Force’s Bomber Command during the Second World War. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross but didn’t talk about his experiences while MacKenzie was growing up.

“What I knew about the war was my dad was a pilot who flew a Lancaster that dropped bombs,” said MacKenzie, a retired lawyer and West Vancouver resident. “I really didn’t know anything else.”

His dad was highly respected in his community, MacKenzie recalled, but he was quiet and could be hard on his son.

That person was very different from the man described by those who knew him – including MacKenzie’s uncle – before the war, “a guy who was funny and relaxed and generous,” said MacKenzie. “Someone who was quite different from the person raising me.”

MacKenzie’s quest into his dad’s wartime history – that this year resulted in a book on Bomber Command – was partly a way to understand what had happened to change his father.

Search for father’s wartime history

The older MacKenzie had signed up for RCAF in 1941 at the age of 29. He knew nothing about flying, said MacKenzie, but graduated from his training at the top of his class, eventually going on to instruct other pilots at a training school in Alberta.

In 1944 he was sent overseas, and was attached to Squadron 166 of Bomber Command, flying 34 bombing missions over Germany.

MacKenzie said he came to appreciate that his dad’s perfectionism – so hard on his son – was the only thing that had kept him and his crew alive in a squadron with a horrifying number of casualties. That came at a cost, however. Post-traumatic stress wasn’t on the radar then, but men like his father came home with huge emotional wounds, said MacKenzie.

In the years after, Bomber Command was pushed further from the public mind by discomfort with the civilian deaths that were also part of its record.

“Bomber Command got totally trashed after the war,” said MacKenzie. Brian McKenna’s CBC film, Death by Moonlight, in 1991, which explored some of those controversies, stirred fierce historical debate and offended many veterans.

For a number of years, MacKenzie’s quest to find out about his father’s wartime record was stymied by his own lack of information from his dad.

But in 2017, a clue from the Royal Air Force in Britain led MacKenzie to RAF Kirmington, site of a once-abandoned wartime air base. As it turned out, Kirmington had been the home base for his dad’s 166 Squadron. MacKenzie flew there to visit. In a local pub, he found memorabilia dating back to the wartime days of the squadron and a guestbook chronicling reunions dating back many years.

From his hotel room, MacKenzie began sending out emails to pilots and crew who had left contact information in the guest books.

That opened a world of information and forged new friendships that would continue over the years, said MacKenzie.

Father flew iconic Lancaster bomber

He learned about the iconic Lancaster plane, the amazing resilience of the aircraft and the near-suicidal conditions with which many of the night-time bombing raids over German weapons factories were conducted.

Years earlier, a Lancaster had been the key to the only time MacKenzie heard his dad talk about the war. They had stopped near a Lancaster on display near Nanton, Alta. On that day, someone had keys to the plane, and MacKenzie and his dad were allowed to sit inside.

“He showed me where each of the seven crewmen sat. And he showed me a little bit of what he did as a pilot,” said MacKenzie.

As they got out of the plane and started driving, his dad started talking about the Lancasters, how they would fly in the dark with no radio contact and no lights on, toward a target. How they would corkscrew to escape the fire from German aircraft once the bombs were dropped.

“What these guys did was simply unbelievable,” said the younger MacKenzie.

Author says Bomber Command should be remembered

MacKenzie said his own belief, based on research conducted over the intervening years, is that Bomber Command’s efforts in knocking out munitions factories remained key to ending the war.

The cost in lives of Canadian airmen was huge, he said. In his dad’s squadron – which operated from January 1943 to April 1945, 944 airmen were killed. Of those, 155 were Canadian.

“I think that Bomber Command needs to be known. It played a decisive role in World War Two. And it’s important that we be aware of this incredible part of our heritage,” he said.

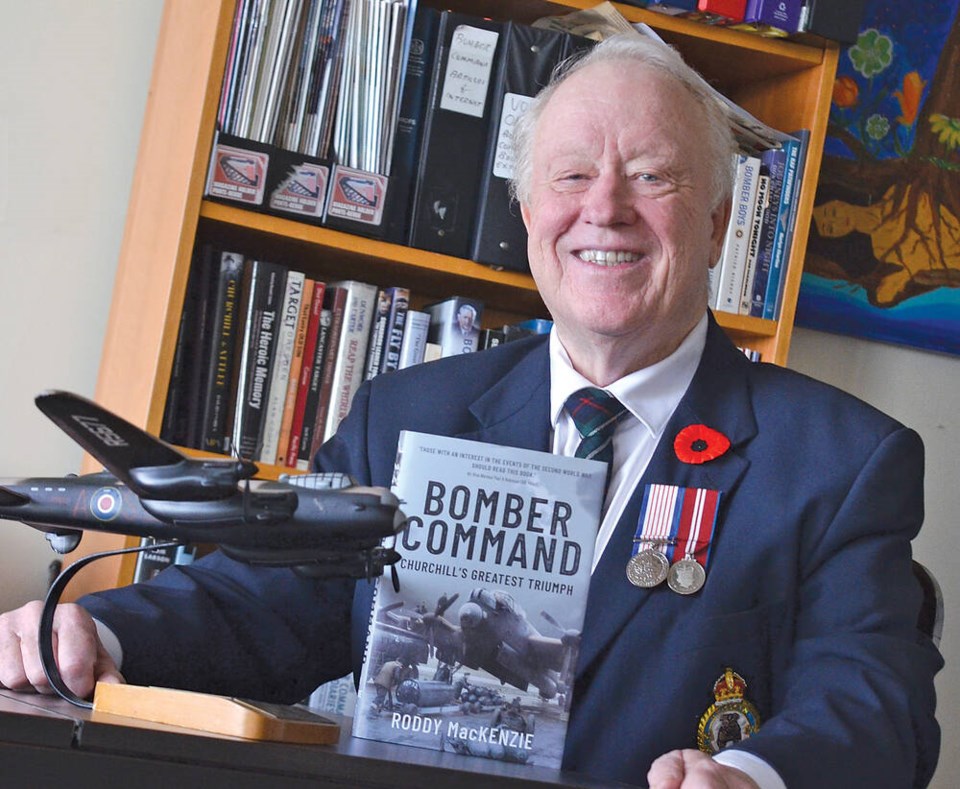

MacKenzie’s book, Bomber Command: Churchill’s Greatest Triumph was published this year by the U.K.-based Pen & Sword publishing house.