A proposed BC Timber Sales Pest Management Plan is gaining attention and fierce push back, as the provincial agency seeks to use aerial and ground spraying of herbicides to increase commercial lumber output.

When Angelina Hopkins Rose’s friend sent her a picture of an official notice in the Hope Standard, the district’s community newspaper, Rose couldn’t believe what she was reading. “We started to look more into it, and it just got worse and worse,” she said.

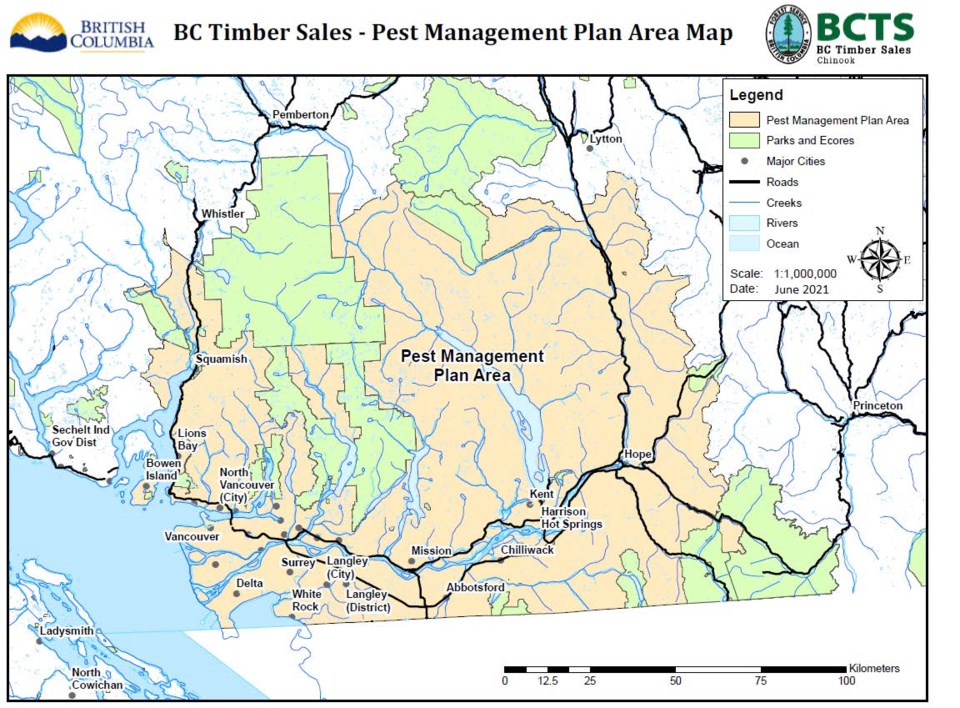

The proposed management plan would come into effect on April 1, 2022, and cover the Chilliwack and Sea to Sky Natural Resources District, including the traditional unceded territories of the Stó:lō, St’át’imc, Nlaka'pamux, xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations. The proposed plan is for five years, ending in 2027.

“It was really scary to me. My partner and I, [we] have a lot of friends who are in activism, we're both Indigenous, we know people from our communities, and nobody knew about it. Nobody had heard about it. And that was really scary,” Rose said.

While the notice was printed in the local newspaper in Hope, along with the draft proposal available online, it does not include a map of specified locations where herbicides such as glyphosate, triclopyr and 2,4-D (Formula 40) will be used. The consultation process so far has been really concerning to Rose, who is now asking for the proposal to be delayed for proper community engagement.

“The email address that they put in that notice [for community feedback] was wrong. … So it feels really disingenuous. It doesn't feel like there has been a consultation period,” she said. “We're asking them to extend the consultation period for 60 days, so our community members, people who live around there [affected areas], First Nations, can actually look at what they're doing, what their plan is, where they're doing it, get a map and figure out how our communities will be affected by this.”

Calling for people to email government officials requesting to delay the spray, Rose posted slides to Instagram on Wednesday (March 23) afternoon, which have since gone viral with more than 1,500 likes and more than 5,200 shares.

The management plan highlights cottonwood, red alder, salmonberry, red elderberry, devil’s club, thimbleberry, salal, fireweed, huckleberry and blueberry as plants which will be targeted by the proposal. All of which, Rose said, Indigenous people have used as medicines and food for thousands of years.

“Killing these plants is going to have serious consequences on our already fragile ecosystems,” she said.

“And we’ve picked in the cutblocks before, which is where they're planning to spray. Without medicine gatherers and berry pickers having a chance to look at the actual map and say, ‘Hey, that's my family’s berry spot. This is where we pick our mushrooms. This is where we pick our medicines,’ we need time to look at that and be able to say, ‘No, you can’t spray here,’” she said.

Rose said the management plan process is “antiquated,” as it only requires it to be published in print, and not online. “The whole process … needs to be a lot more open. The government says, ‘We're working towards reconciliation with Indigenous people,’ [but] there has to be open lines of communication and the map has to be posted. Right now, you have to go to one of their offices in either Hope or Squamish to actually see the map.”

James Steidle, spokesperson for advocacy group Stop the Spray, echoed Rose, and said the process of pest management plans are “completely out of date.”

“If you look at the legislation or the regulations, they're only required to do an advertisement in print media. … They don't electronically advertise the plan, and are not required to do so,” he explained.

Steidle notes the herbicide glyphosate has been subject to ongoing lawsuits regarding its carcinogenicity and adds it has also been found to contaminate vegetation for up to 12 years.

Chilliwack area forests and certainly the forests above Harrison Lake are some of the most intensively sprayed forests in BC.

— StopthesprayBC (@stopthespraybc) March 22, 2022

BC Timber Sales is getting approval for another 5 years of herbicide authorization.

Here's our press release: https://t.co/WLH68DLDQg pic.twitter.com/eDZbSlTOrI

“Despite the claims, the rules do not provide adequate or strict protection of waterways,” Steidle wrote in a release, explaining that when spraying from a helicopter, regulations only require a 10-metre setback from major waterways.

“The entire basis for this program is both unethical and counter-productive,” he said.

Speaking to the North Shore News, Steidle said that the management plan creates a mono-crop-type plantation. “We need these deciduous patches for biodiversity, wildlife and wildfire prevention. A lot of these deciduous species reduced wildfire.”

The coniferous species which usually replace natives like alder and cottonwood are about twice as dark, which contributes to heat retention and wildfire risk, Steidle explained.

“Our rush to get rid of these, so called, competing species is making our forests more vulnerable to wildfire,” he said. “When you get rid of your deciduous for coniferous, your probability of wildfire is exponentially greater. The ecosystem is a complex thing; you need many parts for it to work properly. If you take out all those other parts, you get a tree farm model. That's incredibly risky.”

UBC professor of ecology and author Suzanne Simard told the North Shore News that her research on spraying herbicides in interior forests shows that in most cases it fails to improve conifer survival or growth.

“At the same time, [it] has negative ecological consequences including reduced biodiversity, degraded wildlife habitat, reduced carbon sequestration capacity, increased fire risk and increased erodibility of soils,” she wrote.

“Fire resistant broadleaf trees and understory plants are killed, leaving simplified flammable conifer plantations, which scientists have found in recent years to help propagate fire through landscapes,” Simard noted, adding that this contributes to downstream flooding events.

A copy of the proposed management plan can be found here, while feedback is open until March 27 via email at [email protected].

North Shore News reached out to BC Timber Sales and Squamish Nation for comment. Tsleil-Waututh Nation declined to comment on the upcoming plan.

Charlie Carey is the North Shore News' Indigenous and civic affairs reporter. This reporting beat is made possible by the Local Journalism Initiative.