The boy, 11 years old, watched in terror as his first-ever outdoor climb went horribly wrong in an instant.

Young Sean McColl and his parents – Terry McColl and Anna Lee – had finished their ascent of the famous rocks of the Stawamus Chief in Squamish, B.C. with the help of three guides and were enjoying lunch on top of the world. As they ate, one of the guides showed them the technique they would use to rappel back down.

The guide slung her rope over a boulder and started to inch down the slope, demonstrating the way to lean back and bounce down the rock. But the rope, slung too high, worked itself over the top of the boulder and sprang free, sending the guide flailing backwards towards a cliff.

“She stumbled back and was trying to stay on the rock, but then the next thing you know she was over the edge,” Terry recalls.

The plummeting rope ripped right by Terry and, as instincts kicked in, he grabbed it, slowing the woman’s fall. But he couldn’t hold on. “It went through my hands, burned my hands, and then it was gone.”

Sean, now age 29, remembers those events of 18 years ago precisely.

“I remember the fear of watching my guide go over a cliff,” he says, “and then just disappearing.”

• • •

Sean McColl is speaking on the phone from the Montreal airport, about to head back to his North Vancouver home following another national championship win in sport climbing. These days he’s a figurative and literal rock star at the national championships, bringing with him a resume that includes appearances on American Ninja Warrior – he’ll be featured on the show again in June – as well as four overall titles at the International Federation of Sport Climbing’s world championships.

He’s one of the North Shore’s most decorated athletes – he was named male athlete of the year at this year’s North Shore Sport Awards ceremony after winning another overall world title in 2016 – but outside of climbing circles he’s not necessarily a household name.

That may soon change.

• • •

It was Aug. 3, 2016 and Sean was using his charming smile while working at a trade show in Salt Lake City, Utah, when he snuck away to watch a live-stream video on his phone.

The IOC was announcing the new sports that would be included in the 2020 Olympic Summer Games in Tokyo, and sport climbing was one of the finalists. Sean knew all about the bid, having worked as an athlete rep during the entire process, and was optimistic the sport would make the cut. But you never know until you hear the words. There, in Salt Lake City, McColl heard the words that gave him a gigantic new mountain to climb.

“It gave me shivers when they announced it,” he says. “I knew that that was now my goal for the next four years: to become an Olympian.”

It was a journey that started in a thoroughly inauspicious place: a 10-year-old’s birthday party. The party was held at North Vancouver’s The Edge Climbing Centre, and Sean found himself staring up a wall filled with grips and holds. Like many rambunctious children, he had been climbing things all his life – trees, playground equipment, buildings – but never before had he tried a climbing wall. He shot up that wall in a flash.

“I’ve always been quite a quick climber,” he says with a laugh. “I just loved it. It’s hard to describe. Going up, climbing things, is a very natural movement for kids. So now that I could go up 30 feet and it was hard and challenging – footwork, handwork, all parts of your body, even mental – it was really a cool experience. I just wanted to do it more and more.”

A year later, Sean’s family got memberships to the climbing centre, and soon he was on the centre’s junior team, then he was on the national junior team, then he was a world junior champion. He won the national youth title every year from 1999 to 2005, and claimed five youth world titles, a record that still stands to this day.

“We like to say that we were better than Sean for about two months after we all started climbing,” says dad Terry with a laugh. “That was basically because we all had longer reach and he was pretty small.”

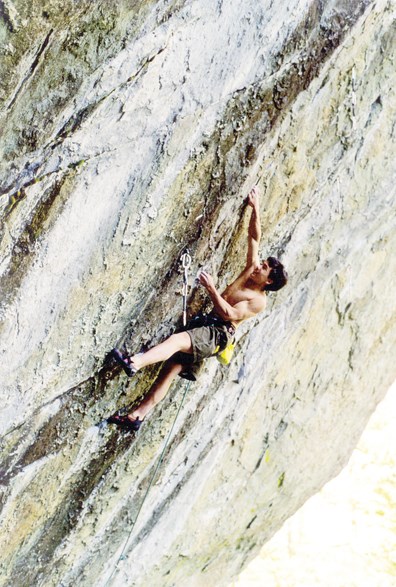

His prowess extended outdoors as well. When Sean was 12 he became the youngest person in the world to ever complete a climb graded at 5.14 (that record has since been broken). Graduating to adult competitions didn’t slow him down, as he has claimed two overall World Cup sport climbing titles and finished second four times, winning 32 World Cup medals in the process, including five golds.

He also holds the distinction of being the second person ever to climb Dreamcatcher in Squamish, a 5.14d route that is one of the toughest climbs in Canada.

He is, without a doubt, one of the best climbers in the world. It’s no surprise then that he caught the attention of the folks who make American Ninja Warrior, the popular NBC series that pits athletes against a daunting, high-flying obstacle course. Never mind that Sean was neither a ninja nor American – the producers shoehorned him into an episode dubbed USA vs. The World, with Sean participating as a member of Team Europe.

“I was living in France, it kind of just works with the show,” says Sean. “They don’t have a Canadian team. Hopefully one year maybe they’ll have a Canadian team.”

Sean has competed three times and has put in some of the show’s most memorable performances. The latest competition will air on NBC on June 4 – it was completed last year but Sean is sworn to secrecy about the result. A downside for Sean is that because he’s Canadian he can’t compete for prizes in the main show, but he says he still has a blast in the USA vs. The World competitions.

“If you win the normal season, you win $1 million. If you win ours, you win, I guess, pride,” he says with a laugh. “And a trophy. … And it’s really fun.”

The show may not have made him a millionaire but he has learned some interesting things about how

bodies work.

“I actually did learn about co-ordination, even more about conservation of energy,” he says. “It was kind of cool seeing that a lot of climbers are actually very good at the courses, especially with the upper body strength. The stuff that we’re weakest at is some of the parkouring stuff where we have to jump in between two walls, spider jumps, or where we get into positions we’re not comfortable with. It’s really hard to replicate them in the climbing world.”

His family was flown in to watch one of the sessions, and dad Terry remembers one swinging chain obstacle that Sean managed to pass despite being completely out of his element.

“He just launched himself off the chains in mid-air, came down and landed on his front and just grabbed the platform with his arms. It knocked the wind out of him, but he stuck it on the platform,” says Terry. “He’s got this ability to think on his feet, and that’s what you need for American Ninja Warrior.”

Competing on the show is just one more line on Sean’s incredible resume. What may be most amazing, however, is the “miracle” that occurred on top of Stawamus Chief all those years back. Without that, it’s quite possible none of the rest of this story would have been written.

• • •

The guide fell close to 100 feet in the air, landing on a bush on a small ledge partway down the rock face. Anna, a registered nurse, did a speed rappel down with one of the other guides to assess the situation.

The rest of the team soon joined them, along with another climbing group that had seen her fall and gotten to her first. She was, incredibly, alive and awake. The gravity of the situation was made all the more clear when they looked over the edge of that small strip of rock where she landed. Below them was nothing but 700 feet of air.

The woman – Terry says he doesn’t even know her last name – was somehow relatively unscathed, with only minor cuts and bruises. She wanted to walk back down but the rest of the climbers made her wait for a helicopter rescue.

At the hospital the doctor that examined her was initially baffled by her injuries – the worst seemed to be some strangely shaped bruising around her hips. Once the rest of the climbers arrived they figured out that it was a bruise that exactly matched her harness – the working theory was that Terry’s grab of the rope jolted her to a near stop, slowing her descent. Even though he didn’t catch her, his grab may very well have saved her life.

“To go over a 100-foot cliff, hitting the rocks a couple of times, and being able to walk away from that – it was definitely sort of a miracle,” says Sean.

Terry’s hand actually suffered the worst injury of the day, his ring finger sustaining third degree burns. There’s still a small scar on his right hand that serves as a reminder of that day. Sean and Terry agree that their lives may have turned out much differently if there had been a different outcome on top of the Chief.

“If she had died there, I really wonder,” says Terry.

“I think the reason it didn’t throw me off of climbing or do anything that would have scarred me for life is that she walked away from the incident,” says Sean, adding that he’s not sure he would have ever climbed again if the woman had died. “I think it really helped that my parents, my coach, the other guides – they just executed everything perfectly. There was no panicking.”

It took six months away from climbing, but the whole family eventually got back on the rocks, now imbued with an even greater sense of caution that persists to this day.

For all of his countless hours spent climbing indoors and out, Sean says he’s never had any close calls.

“It made me realize that climbing is an inherently dangerous sport if you don’t follow the proper safety procedures,” he says. “How many times have I tied in to a rope and gone for a rock climb? Way more than I can count. And it only takes one time when you forget to do something, you let go and you fall. … I check all my systems many times, because you can never check it too many times.”

That approach has helped Sean climb to heights no other Canadian has ever achieved. After all these years, he’s now working harder than ever because he has a new prize to reach. Whoever wins gold in Tokyo will go down in history as the first-ever Olympic champion in sport climbing.

“I was the first Canadian to do many things: win a world championship, win a World Cup, win an adult world championships,” says Sean. “And now the prospect of getting to the Olympics – I could be the first Canadian Olympian in rock climbing, and I could also be the first Canadian to win a medal, and that medal could be gold. That is everything that I want.”

He’s got a pretty good shot too. The Olympic competition will be a combined event, featuring total scores from the three main climbing disciplines of lead, bouldering and speed. Sean is one of the few climbers in the world who is not a specialist. He consistently competes in all three, excelling in lead and bouldering while also holding his own in speed. He is, after all, the defending overall world champion. Why not Olympic champion too?

“It opened up a door that I’ve never walked through before, and it gave me a goal that I’ve not achieved,” Sean says of last year’s Olympic announcement. “That’s what has always driven me as a climber, since I was a kid. It was always achieving something that I hadn’t achieved, pushing myself to the next limit. … In my heart, I love competing. It is something that I’ve always said. I love being in a competition, I love the feeling of it, I love testing myself in front of cameras, in front of an audience. I’m very excited about becoming an Olympian because I know that the stage is even bigger than what I’ve ever competed on before.”

Sean McColl’s latest stint on American Ninja Warrior will be broadcast June 4, 8 p.m. on NBC.