When the Second Narrows bridge collapsed in 1958, one of the first rescuers in the water was Phil Nuytten.

The 17-year-old from North Vancouver was the go-to guy for diving gear, having founded the West Coast’s first ever dive shop two years earlier. At 15, he wasn’t old enough to get a business licence so his mother put it in her name.

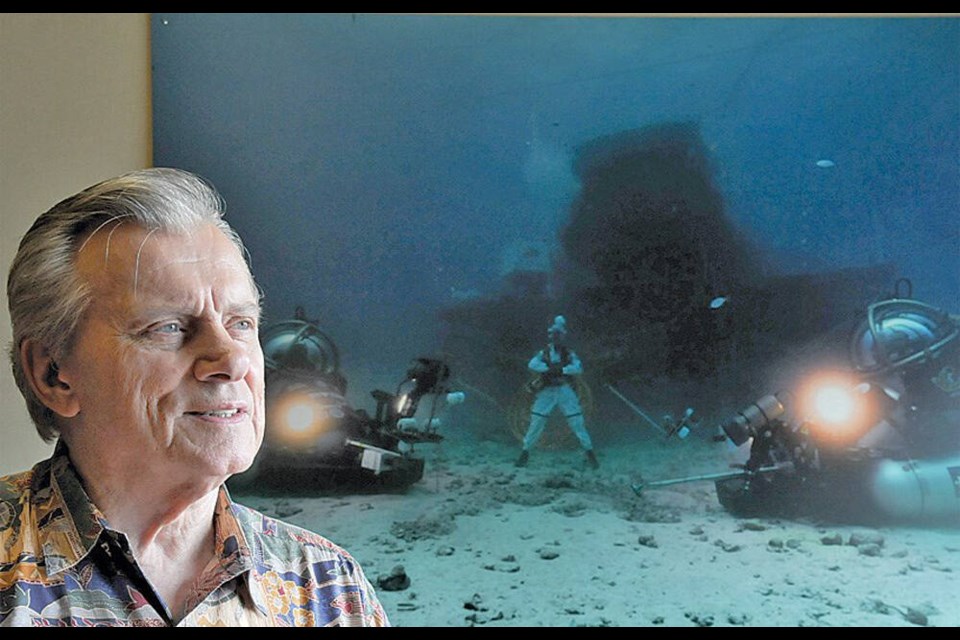

Since the bridge collapse, Nuytten spent a lifetime dedicated to research and innovation of submersible diving suits and submarines to make exploring the world’s oceans safe.

He died on Saturday, after a short illness, at the age of 81.

“There’s been all sorts of things said about him. The most common one is ‘Renaissance man,’ but I always think of him as sort of a going concern,” said Virginia Cowell, Nuytten’s daughter who still works in the family business. “He was always going in five directions and had projects on the go at all times. I’m surprised the man had time to sleep.”

Nuytten founded numerous companies that spread around the world, including Oceaneering International Inc., Can-Dive and Nuytco. Their works opened up new ways to reach the deep sea for academics, the private sector and the world’s navies.

Much of Nuytten’s work was done at his East Esplanade office – the only one in Lower Lonsdale to have a 110,000-litre dive tank in the parking lot, used for everything from testing new inventions to training NASA’s astronauts.

Historic discovery

In the 1970s, he became famous for his Newtsuit, an underwater exosuit that made it possible for a single diver to explore depths never previously possible. He appeared on the front cover of the July 1983 National Geographic being hoisted from the ice following a dive to the shipwreck of HMS Breadalbane, one of the ships lost in the 1853 manhunt for the ill-fated Franklin Expedition.

In 2014, Nuytten told the North Shore News about the experience of spotting the mast of the ship 100 metres below the Arctic Ocean ice.

“I could see the whole wreck under the light of this big candelabra and it was absolutely incredible. It was covered with orange and saffron growth like anemones and the hull, because it was copper sheathed, it had this incredible turquoise patina. It was just beautiful sitting down there,” he said.

NASA, Nat Geo and the Navy

Because of his expertise, Nuytten was sought by Hollywood’s elite filmmakers to advise them on shooting under water. James Cameron was one of his clients. He was featured in dozens of documentaries.

NASA and the Canadian Space Agency were regulars, as piloting his submersibles is the closest thing on earth to piloting a landing craft that one day might touch down on the surface of another planet.

Cowell said her father was most proud knowing that fellow divers could do their work in the beautiful but potentially deadly undersea and return to the surface with ease.

“People are now safely exploring the world’s oceans without risk of the bends. That’s a huge one,” she said.

A particular favourite was his Remora, a submersible designed specifically to carry out rescues of crew members trapped in sunken or disabled submarines. Versions of it are in use by several of the world’s navies, Cowell said.

Cowell described Nuytten as a “natural engineer.”

“He could see a problem and find a way around it. Wherever people saw roadblocks, he just saw opportunities to find new ways to do things,” she said.

Indigenous artist

When Nuytten learned as a boy that he was of Métis heritage, he set out to connect with his Indigenous roots. He became a master carver and engraver, working in the style of the West Coast Kwakwaka’wakw Nation, who adopted him in. His pieces were sought in galleries specializing in Indigenous art, and he took very seriously his role in keeping the cultural traditions of his adoptive family alive.

“It was his passion. He was such an unbelievably talented artist,” Cowell said.

There was most certainly overlap between those two worlds, Nuytten would say. At the bottom of the ocean, he’d be thinking of designs for a new bracelet or ceremonial mask. During a potlach dance, he’d be imagining new exosuit components.

“No napkin was safe in the house because he would be doodling on it. There’d be drawings everywhere,” Cowell said. “Whether it was a new joint or some new piece of tech or whether it was a new pattern.”

Though he’s best known for his inventions and his artworks, Nuytten was also a passionate activist for ocean health, especially the ending of fish farms on the Pacific Coast, Cowell said.

“He had a real attachment to nature,” she said.

Unfinished business

He had even more ambitious dreams that, for now, remain unfinished business, including restoring the famous Expo 86 McBarge into a floating museum dedicated to the West Coast’s undersea innovation history, and Vent Base Alpha, an underwater colony meant to simulate the conditions of, and prepare astronauts for, life on Mars.

His list of accomplishments was as deep as the abyss. His breakthroughs in engineering allowed more breakthroughs in marine biology and other fields. His recognitions were many, including being named to the Order of B.C. and Order of Canada.

Cowell, though, described her father as an idyllic family man and compassionate individual who would jump at the opportunity to help someone in need. He was predeceased by his wife Mary – whom he absolutely adored, Cowell said – in 2021.

Since word of Nuytten’s passing has spread, Cowell said she’s been a bit overwhelmed with people wishing to express their condolences. Cowell said she believes her father’s legacy and businesses will carry on.

“I think that there’s probably a million things that were just rattling around in his brain,” she said. “Some of them got a little bit of a start and we may continue on.”