He’s heard from his share of treasure hunters.

They need his dive suits and subs, they’d explain. The would-be scavengers couldn’t pay in advance, of course, but they’d be very happy to split the bounty beneath the waves.

Inventor and entrepreneur Phil Nuytten chuckles as he recounts the tale.

The Egyptians’ chariots are still there under the Red Sea! a wide-eyed hunter once informed him as he quoted liberally from the Book of Exodus.

“I said, I’ll tell you what, there’s another company . . .” Nuytten recalls replying.

“We’ve been to this rodeo many times before,” he says.

But earlier this year the Shinil Group out of South Korea offered a concrete proposition: locate, survey, and identify the Dmitrii Donskoii.

The Russian cruiser first drifted into his consciousness 30 years earlier, Nuytten recalls. He’d been having dinner with an older gentlemen who once served in the Japanese Navy.

“He was at our house one day and we were talking about shipwrecks and I was laughing about treasures,” Nuytten says.

The conversation swung toward a ship that had been sunk more than a century earlier. And when it made that plunge, so the story, went, it was carrying tons – literally tons – of gold.

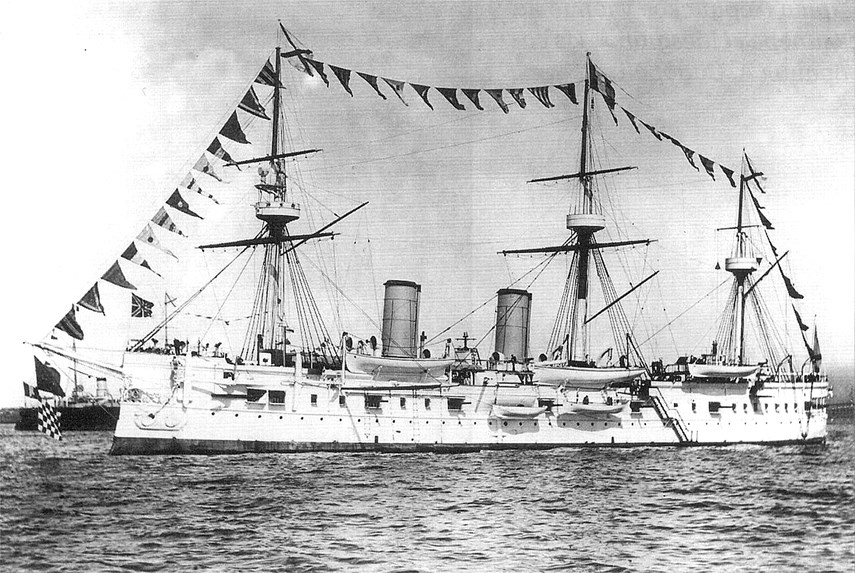

The Dmitri Donskoii was about 20 years old in the spring of 1905. That’s when Czar Nicholas II launched the Donskoii and his Baltic Fleet halfway around the planet to the Sea of Japan.

The ships were re-enforcements in a port war that was ostensibly lost, even surrendered.

Even by the standard of 18,000 naval voyages, the Donskoii had a rough trip.

The fleet just about started the First World War a decade early when the commanders mistook a few British trawlers for Japanese warships and opened fire.

Three fishermen were killed. The Donskoii, which was also mistaken for a Japanese boat, was also bombarded.

Suitably unimpressed with Russia, the British navy essentially blocked the Suez Canal, forcing the fleet to sail around Africa.

The mission concluded when the ships entered the strait separating Japan from Korea.

Approximately 5,000 Russian troops died and eight battleships were sunk in Tsushima Strait.

The disastrous defeat led to a peace agreement. But in the immediate aftermath, the captain of the Donskoii is believed to have ordered the ship sunk near South Korea.

The rumour – long guessed at but never proved – is that billions of dollars of gold went down with the ship.

“The myth or the story or whatever it is, that the reason they didn’t want the ship to fall into Japanese hands was because it was containing all this gold,” Nuytten says.

Historian and author Constantine Pleshakov completely dismissed the theory.

In his book, The Tsar’s Last Armada, he writes of the Donskoii: “She was a very old and slow ship, one of the notorious clunkers with which the Russian sailors were so frustrated – a very unlikely candidate to be entrusted with transporting a tenth of all the gold ever mined in the world, not to mention that even though Tsar Nicholas II was rather thickheaded, he would never have ordered the transport of such a large amount of gold by ship from St. Petersburg to Vladivostok when he had the Trans-Siberian Railroad at his disposal.”

The debate over the lost gold may be ending soon. Going to depths of about 1,400 feet, Nuytten’s team found the ship on July 14. It was painted red and green with rust and algae, but the cannons and guns, the masts and armour were still in place.

In a YouTube video chronicling the operation, we even see the name of the ship.

“You’re not going to believe it, I have a name,” the pilot calls out. “It’s in Russian,” he says before adding: “I can’t read it.”

After 113 years, the Nuytco DeepWorker team located the ship in two days.

“They were beside themselves with joy when we identified it as the right ship,” he says.

The hull is in pretty good shape considering the wear and tear of a century in the sea, he says.

“If they don’t care about its historic value and they’re only after the gold well, then the thing to do is to get out there with a big barge and a crane.”

The other option, Nuytten says, is an explosion.

“You simply blow the ship apart and then pick up the pieces,” he says. “We’ve done that also.”

While no formal agreement has been struck, Nuytten says they’ve had conversations about participating in the salvage.

But despite the enormity of the find, Nuytten emphasizes that he’s not interested in a share of the loot.

“We’re interested in the day rates,” he says.