As attention around the world is gripped by the desperate search for a submersible that vanished near the wreck of the Titanic, there’s one thought that Nuytco Research’s Jeff Heaton keeps returning to: “The clock is ticking.”

Heaton, operations manager and chief submersible pilot for the pioneering North Vancouver research company founded by the late Phil Nuytten, knows two of the five people who are on the missing submersible, which lost communications contact Sunday while descending to the wreck of the famous ocean liner off the coast of Newfoundland.

The dive community is small, he said, so he’s met Stockton Rush, the CEO and founder of OceanGate, the company running the expedition to the Titanic, who was on board the Titan submersible. Heaton has also met Paul-Henri Nargeolet, a submersible pilot who is “very well respected in the industry” and “has more divers on Titanic than anybody else on the planet," said Heaton.

"He's a great guy," he said. "I've had the pleasure of speaking with him and hanging out with him a few times."

“It’s a pretty tight knit group of people,” among submersible pilots in the diving community, he said. “There’s not that many of us.”

But assuming the submersible is still intact, the life support system only has enough oxygen for those inside to survive 96 hours. That window had narrowed to less than 40 hours by Tuesday afternoon.

“Watching the clock tick down, it’s not easy to watch,” he said. “We’re hoping for a positive outcome.”

Experimental design

In some respects, the missing submersible is like others operated commercially all over the world, said Heaton – it has a propulsion system, ballast tank, emergency life support, acoustic communications link with the surface and it can only operate for a finite period without returning to its mother ship on the surface.

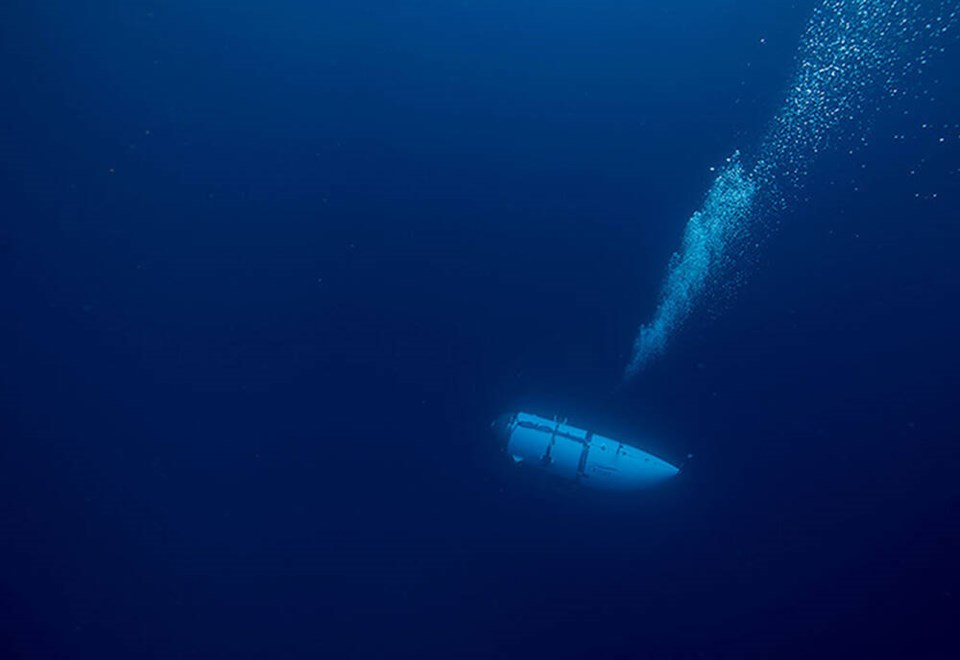

One key difference between more regular commercial submersibles and the one used by OceanGate for its Titanic exploration is “this vehicle is experimental in nature,” said Heaton. “It uses a carbon fibre main hull section” considered a “very new exotic material.” Most deep-sea submersibles, including the Russian-made MIR submersibles that have made trips to the Titanic are made with titanium, or special submarine grades of steel alloys that allow them to operate at depths, he said.

Those are also the materials used in submersibles that have been certified by agencies like Lloyd's that ensure the subs meet certain safety standards.

All submersible pilots have protocols they follow in event of an emergency, said Heaton, which usually involve surfacing the sub in the event communications contact is lost. (That’s why the search initially focused on the surface of the ocean.)

But “to have a total loss of contact is very rare,” he said.

Worst-case scenarios include the submersible becoming entangled with objects (when communications should still be functioning), a fire onboard or a catastrophic system failure that would include loss of power.

Finding submersible will be challenging

If the submersible is still intact, the next big obstacle will be finding it, he said.

The wreck of the Titanic is in extremely deep water – about 12,500 feet down.

“It compounds all those issues, said Heaton. “It’s very difficult to perform a rescue at that depth.”

“One of the things that doesn’t get talked about much is the currents around Titanic on the bottom are actually quite strong,” he said. “It becomes a pretty big search area, and that search area increases day by day. It’s a big ocean.”

Heaton said searchers are likely listening with sonobuoys to see if they can pick up any sounds underwater and may be using side scan sonar of the ocean floor that would give them clues about the sub’s location.

One of the systems Nuytco makes is a submarine rescue system. That system, however, is designed to lock on to a standard military submarine hatch, said Heaton.

Industry has excellent safety record

Since the discovery of the Titanic in 1985, submersible trips to the wreck by researchers and filmmakers aren’t new, said Heaton, although deep-sea ‘tourism’ trips are more recent.

Heaton said despite attention on the missing submersible this week, the industry has an excellent safety record. While there are always inherent risks and dangers in diving with submersibles, “I’ve been doing it 30 years with no incident,” he said. And in tens of thousands of submersible dives since the 1960s, there have only been three fatalities, he said.

While the clock ticks down this week, Heaton is hoping for the miraculous – that the submersible can be found in time and recovered. He said he will continue to hope for that, despite his first-hand knowledge of the odds.