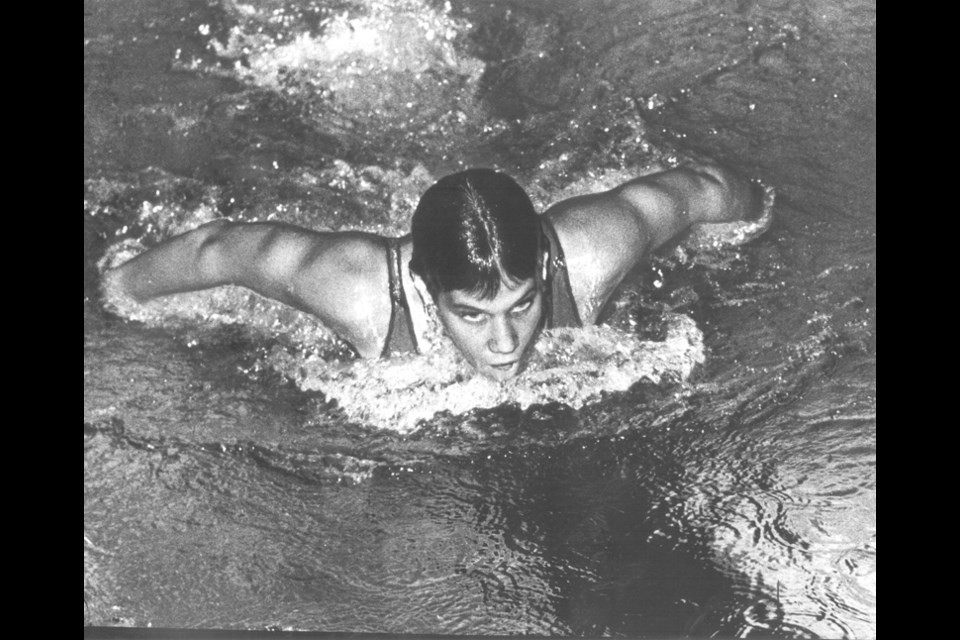

They called her Mighty Mouse.

For a generation of Canadians in the 1960s, she was an athletic hero – a swimming star of the finest caliber, in possession of such speed and finesse in the pool that onlookers were sure her talent could only come along once in a generation.

To a large extent, they were right. Mighty Mouse broke a number of records, many of which remain unbroken. She took home a staggering seven medals in the 1966 Commonwealth Games, and in the 1968 Olympic Games she earned three medals for Canada. She was 17 years old at the time.

But then shortly after the Olympics, Mighty Mouse retired from the sport, mainly disappeared from public life, and spent the ensuing decades trying to figure things out.

She didn’t reemerge for a long time.

• • •

Before she was Mighty Mouse, she was Elaine Tanner, who grew up in West Vancouver.

Earlier this month, Tanner found herself back on the North Shore on the Capilano Suspension Bridge, thrust into the athletic spotlight in a way she rarely is these days.

In the lead-up to the 2018 Commonwealth Games in Gold Coast, Australia, Tanner was asked to be part of the Queen’s Baton Relay, an event held prior to the games where a baton containing a message from the Queen is relayed throughout all the Commonwealth countries.

“The BC Sports Hall of Fame said, ‘Well, we have an iconic Commonwealth athlete.’ They asked me if I’d do that, and hold the baton running across the suspension bridge,” Tanner explains. “I loved it up there.”

As far as the Commonwealth and BC Sports Hall of Fame is concerned, Tanner is a swimmer. She recognizes how important this part of her legacy is, but admits she doesn’t identify as an athlete the way she once might have.

“I’ve done the swimming thing. I’ve don’t that. I’ve got other roads and paths to go down. I want to go down a new adventure, I want to see new things,” she says.

It would make sense that Tanner feels this way – she hasn’t raced competitively for a long time. And the last time she was thrust into the public spotlight as a swimmer, she feels like she was betrayed by the media, which in turn precipitated years of hardship. But as friends, acquaintances and swimming experts can attest, Tanner’s story is more about her prowess in the pool and zest for life than the difficulties she may have faced along the way.

• • •

Elaine Tanner was born in 1951 and spent her primary years in West Vancouver.

“West Van was just a wonderful place to grow up,” she says. “Back in the ’60s it was just so beautiful, and we didn’t have all the highrises or the traffic. It was really a paradise.”

Tanner and her family moved to California when she was four, after her father got a job near Santa Clara. It was there where the allure of the pool first became apparent.

“I caught the bug. I went, ‘Wow, I could do that,’” she says. “I pretty much hopped into the pool and taught myself.”

When Tanner was nine, the family moved back to West Vancouver and she immediately joined the Canadian Dolphin Swim Club under the legendary Howard Firby.

Firby, who was inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame in 1977, was known as a brilliant developer of talent and an excellent technician able to take a swimmer’s stroke to the next level. With Tanner, he had his greatest protégé.

“We just made music together,” she says. “He knew how to coach and I knew how to swim and I just went up and up and up from there, and the rest is history.”

That history began to really come together in 1966.

Before heading to the Commonwealth Games in Kingston, Jamaica, that year, Tanner recalls a reporter asking her what she hoped to achieve. “I couldn’t imagine coming back with medals. I had no idea,” she says. “I wasn’t in the public eye – yet.”

Tanner would end up making Canadian swimming history by winning a record seven medals at the games, including two world records for her gold-medal performances in two butterfly races.

It was around this time that her Mighty Mouse nickname, a title bestowed upon her the year before, started to gain traction in the press.

“I was tiny. I was like 4-foot-9 and 95 pounds,” she says. “I was small but I was strong.”

• • •

Tanner has no memory of standing on the podium at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City to receive her silver medal. It was a rare instance where Mighty Mouse didn’t feel so mighty.

With enormous pressure from the press and the country as a whole – not to mention her own high expectations – Tanner wasn’t prepared for anything less than a first-place finish.

“When I started winning all these things you get put up onto a pedestal and the public pressure, especially back then … as much as you try to ignore that pressure, you’re immersed in it,” she says.

She ended up finishing second behind American swimmer Kaye Hall in the 100-metre backstroke, falling behind by a mere half-second.

Tanner also brought home a silver medal in the 200-metre backstroke and a bronze in the 4x100-metre freestyle.

“From 1932 all the way to 1968 we had women in every Olympic Games, but never anyone a medalist. Elaine Tanner was our first Olympic women’s medalist,” explains Jack Kelso, a retired faculty member at the UBC School of Kinesiology.

Kelso, who’s written a massive book on the history of competitive swimming in Canada and is currently working on a tome about Vancouver’s legendary Canadian Dolphin Swim Club, says Mighty Mouse is in a league of her own when it comes to her stature as a Canadian swimmer.

“The biggest problem that she had personally was that she actually went into the Olympic Games in Mexico City as the favourite to win both the 100- and 200-metre backstroke,” Kelso says. “She was very shocked to find out that she really didn’t perform up to not only her expectations, but the press’s.”

At 17 years old, Tanner was forced to carry Canada’s gold-medal hopes on her back. When she didn’t deliver the gold, she paid the price for it with her own mental health.

“Remember back in the ’60s there was no such thing as sports psychologists. There was no support for me emotionally or physically. I was just there on my own,” Tanner says.

“Even though I came back with three of the five medals … as soon as I finished my race the media came up to me and said, ‘Why did you lose? Why did you lose?’ It was all negative and they didn’t understand what they were doing to me.”

• • •

Tanner didn’t find solace when she returned home to West Vancouver. She graduated high school in 1969 and spent the following decades moving from place to place, trying to find herself. She married in her early 20s and had two children, but the union didn’t last.

“Because you’re not right with yourself you can’t expect a relationship to be right either. That eventually ended up in divorce and through the divorce I lost the kids, they went with their dad. I actually went into a spiral downwards,” she says.

While Tanner should have been celebrated for her Olympic achievements, the rest of the world’s focus on her lack of coming up with gold cracked the foundation of her self-worth.

“(If) I’m not a winning swimmer – who am I?” she says. “I started to fall apart.”

For decades, Tanner’s inner conflict manifested itself through eating disorders, anxiety attacks, and her apparent inability to hold down a job or stay put.

At one point in the 1980s, Tanner says she contemplated ending her life. But, as begets her sunny, positive outlook, she doesn’t want to unnecessarily dwell on the past.

“I don’t want to make it negative because it’s not a negative story,” she implores.

• • •

The first time that Cecelia Carter-Smith met Tanner was 51 years ago at the Commonwealth Games.

Back then, the humiliating practice of gender testing female athletes was in full swing and she recalls having to stand side-by-side with Tanner as they were examined by a panel of people tasked with determining that female athletes had the “proper anatomical parts.”

“Elaine was very young and quite frightened by that and I tried to reassure her,” Carter-Smith says.

But even though Tanner was young back then, Carter-Smith, who was a renowned track and field athlete, still sounds in awe when describing her grace in the water.

“As an athlete she was in a league of her own, but as a human being I would say she’s at the top of the mountain,” she says.

At the end of the day, she adds, she connects more with Tanner as a person than as an athlete. Carter-Smith is a passionate proponent for Canadian athletes, and laments the fact that, to her mind, Tanner has never received proper dues for her contributions to Canadian sport.

But she admires the way that Tanner’s been able to pull herself out of the darkness and shine a light for those around her. She describes Tanner’s current husband, John Watts, as “her greatest victory in life.”

In the late 1980s, Tanner married John, a man she says “believed in me when no one else did.” As she recovered her footing over the last few decades, Tanner’s made up for lost time.

Today, she’s a passionate advocate for mental health and well-being, a writer, academic and athletic spokeswoman. She also reconnected with her children – and grandchildren.

North Shore sports historian and longtime columnist Len Corben credits the North Shore’s strong culture of athleticism for producing such top-notch talent.

“One of the greatest performances in Canadian swimming history is her performance in Kingston at the Commonwealth Games,” Corben says. “I think it’s the parents and the culture of the North Shore that says sports is important. That was the same back in Elaine’s day, too.”

To Mighty Mouse’s mind, she still has a few more performances left to give.

• • •

In 2015, Tanner wrote a children’s book called Monkey Guy and the Cosmic Fairy, a charming story about unconditional love and friendship.

She says she was inspired to write the book because of her three young grandchildren.

“There’s an ending to the story,” she says, as if referring to her own epic journey. “I wanted to write them a magical story that had a message of life in it.”