Everyone over the age of 65 in Metro Vancouver remembers where they were when they heard the Second Narrows Bridge had collapsed, resulting in the deaths of 19 workers. Now some never-before-seen footage of the bridge in the moments before and after the 1958 disaster is set to bring those memories rushing back.

Draftsman Peter Hall was running late for work that day. The Dominion Bridge Co. had asked him to bring his wind-up 16-millimetre camera to the job site a few days a week to document the construction. By June 1958, he’d gathered 3,000 feet of film (about an hour and a half).

But after the bridge came tumbling down, the company lost interest in doing anything with the film. Twice, Hall tried to return it to his supervisors but was rebuffed. It ended up sitting on his shelf for 59 years until Hall gave an interview to his local paper in Parksville and mentioned he’d like to see something done with it. The story caught the eye of North Vancouver journalist and documentarian George Orr.

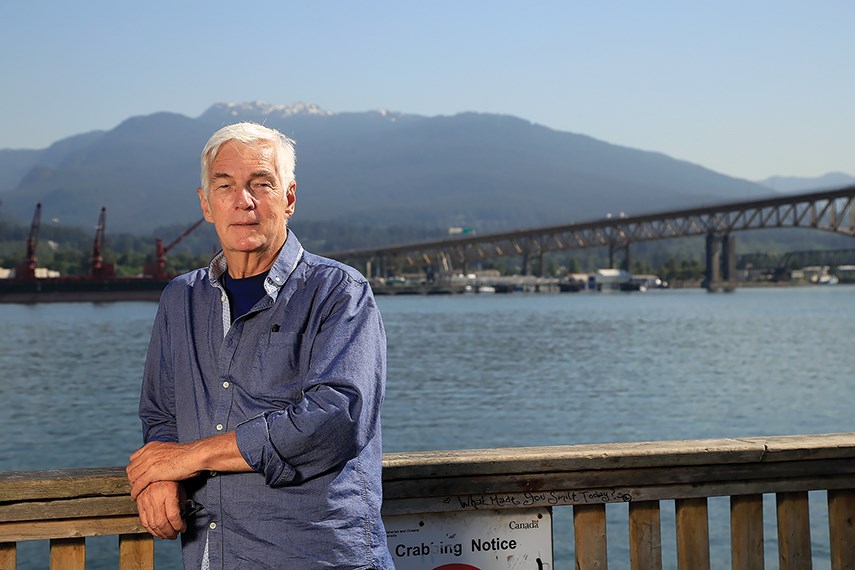

“I phoned him and said ‘What’ve you got?’ and I was astounded what he told me,” Orr said. “As he described what he had I was thinking, this can’t be real. Like 60 years later, the undiscovered treasure.”

The two arranged to meet to have the footage digitized.

“The morning I looked at it, I was just overwhelmed. I thought ‘Well, I now have a duty to make something out of this that will acknowledge what he did and what the men did who built the bridge,’” Orr said.

The footage puts the viewer in the boots of the ironworkers themselves. It includes everything from the steel being cut and bound with red hot rivets at a foundry in Burnaby to cranes hoisting the 55-tonne beams up 60 metres over the rushing narrows below. The workers casually lug heavy tools around the narrow girders but, astonishingly, they’re wearing life-jackets, not safety harnesses.

"The Bridge" coming soon from George Orr on Vimeo.

After the feelings of vertigo subsided, Orr said he was left just feeling admiration for the workers.

Orr spent hundreds of hours editing interviews with the journalists who covered the story at the time, investigators, longshoremen, and salvage divers but it’s the interviews with the survivors that are most poignant, the pain of the memory still palpable.

“That was the intent of the story – to get people to care about these old guys. When you watch them talk, you’re actually hearing somebody 60 years younger in their memory,” Orr said.

As a documentary, it’s very much a tribute to the men who died and to the survivors, but it’s also partly an engineering lesson and a mystery in its review of the evidence of exactly what went wrong.

The bridge collapse was due to a mathematical error in the design drawings that wasn’t caught by plan checkers. The 21-year-old engineer and father-to-be who made the mistake was among the dead.

The first public screenings of The Bridge are scheduled to hit the screen at Vancity Theatre on June 17 – the 60th anniversary of Vancouver’s worst industrial disaster. Another screening is scheduled for June 20.

“It’s a fascinating story,” Orr said. “It’s a fascinating piece of the history of this city and of this region. If you’re at all interested in Vancouver as it used to be … this is an opportunity to look back through a really interesting window to get a sense of it.”

Tickets are $9 for youth, $11 for students and seniors, and $13 for adults, available at VIFF.org.