When Ocean Hyland walked along the narrow industrial alley in Vancouver’s Mount Pleasant neighbourhood, she was caught in a time warp.

As a member of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation, she had grown up listening to the stories of how her great-great grandmother would harvest clams on the North Shore and bring them to Vancouver to sell. Hyland knew that the Tsleil-Waututh, Squamish and Musqueam First Nations had never ceded or given away its legal rights to this strip of asphalt that ran parallel to West Third Avenue, nor any of the lands upon which Vancouver was built. This was a place of her past but it looked absolutely nothing like how the past had been described.

How could her rootedness in the past jibe with the present-day reality? And what did it have to say about Indigenous people’s role in the city’s future?

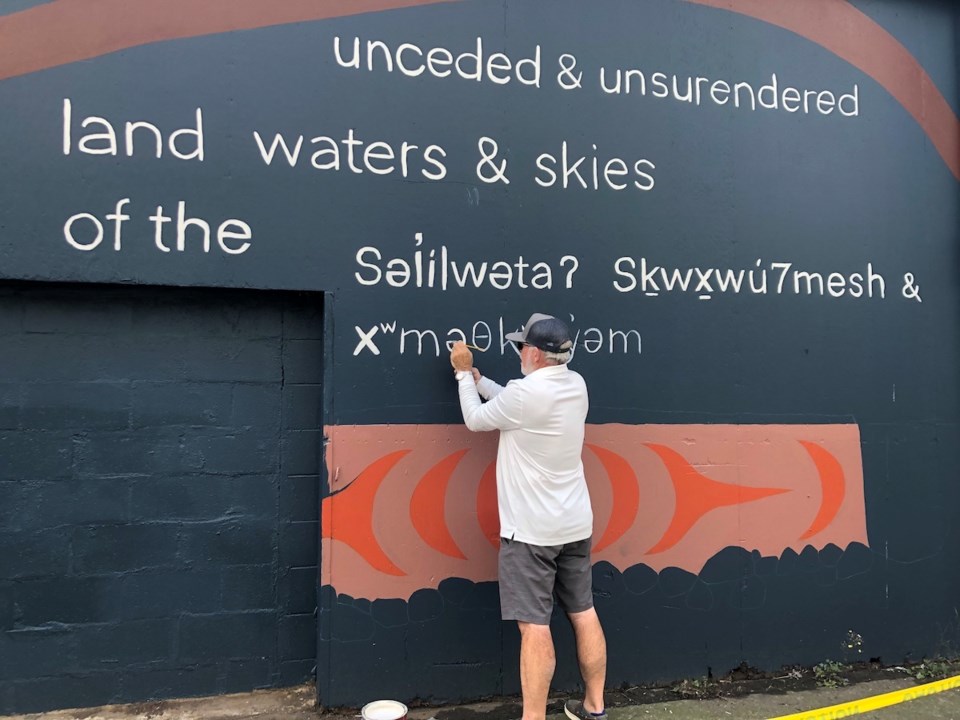

Then she took out her paintbrush. The results of her introspection are on display as part of Vancouver Mural Festival, which runs until Sept. 7 (although of course her mural will remain on the wall for years.)

Hyland’s mural is on the alley that runs parallel to West Third Avenue between Manitoba and Ontario streets. It is one of 60 new murals commissioned by the festival as part of its free celebration of the power of art to reflect our lives back to us. Building walls become canvases; streets become galleries.

Coming up with a design for such a huge space was initially a challenge. Hyland had to see the space in context of its location before she got a clear sense of what message she wanted to convey.

“We have to maintain the history of our old stories but also add in what we’re experiencing today,” she says.

Her mother is First Nation; her father’s ancestry is Scottish/Irish. She grew up immersed in Indigenous culture and heritage but she’s also very attuned to the present. When you go to her website, her portraits are an intriguing blend of traditional First Nations art styles in a thoroughly modern context.

“When I was younger I obviously relied on a lot of the stories and teachings that were shared with me about my family but since then I’ve learned how to interpret those stories and create art that represents those teachings but in my own voice,” she says. “I love the feeling that I’m connected [to First Nations traditions] but I can still go into the world and understand what’s going on, and my place here.

“One of my mentors talks about it as being a bridge between our old ways in our culture that’s still alive, and still engaging with people who are not from here. It’s being able to translate what we know into a way that they would understand as well.”

There are several elements to the mural.

One is her take on the “Welcome to Vancouver” sign that greets people as they enter the city. That Vancouver embodies towering condo buildings, bustling restaurant districts and Seawall strolls. But it doesn’t acknowledge the three First Nations — Tsleil-Waututh, Squamish and Musqueam — who never signed away their legal rights to the land.

Hyland replaces “Welcome to Vancouver” with “unceded and unsurrendered land water and skies of Səl̓ílwətaʔ Sḵwx̱wú7mesh xʷməθkʷəy̓əm.”

Another prominent component is her ponderings of what will be the future once First Nations are recognized as a valued part our shared narrative. Yes, she wants visitors to understand that they are entering unceded territory but even if First Nations one day get their territory back, and the land and waters are once again healthy, people will keep coming.

Who, she asks, will be our next visitors?

That’s why there’s a singing wolf greeting a spaceship.

“We have a protocol,” Hyland says, “when we meet new people who arrive. We usually sing [as a form of communication]. It’s like saying, ‘Where are you from? This is who we are. This is what we believe in. Who are you and what kind of values do you have?”

First Nations will never again be the only ones here. The people who joined them can’t be sent away. New people will always arrive.

Welcome, the mural says, but always remember where you are.

Find out more about the Vancouver Mural Fest, its activities and its artists here. Martha Perkins is the North Shore News’ Indigenous and civic affairs reporter. This reporting beat is made possible by the Local Journalism Initiative.