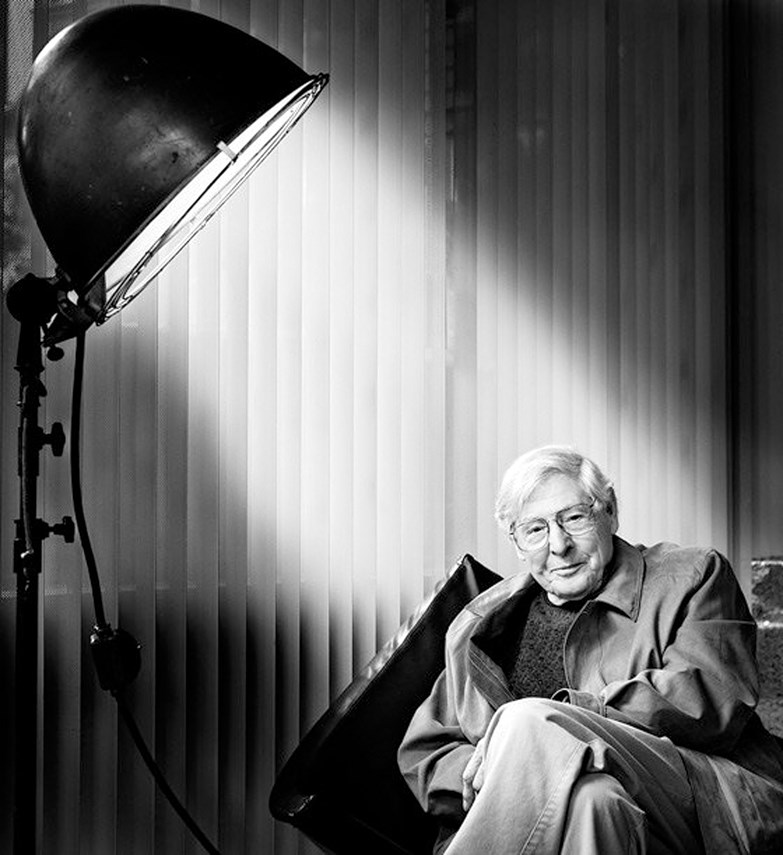

From behind the lens of his homemade camera, Selwyn Pullan captured a movement.

A sought-after architectural photographer, the longtime North Vancouver resident focused his talents on the West Coast modern design style that emerged in B.C. in the post-war period.

Pullan died Sept. 25 at the age of 95. He is survived by his wife, Margaret Redpath, his daughters Joanne and Wendy, and several grandchildren and great-grandchildren. He also leaves behind an extensive body of work that immortalizes local houses and buildings from the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, many of which have since been demolished or renovated beyond recognition.

Adele Weder, founder of the West Coast Modern League and interim editor of Canadian Architecture magazine, describes Pullan as “a gracious, thoughtful man” who was an important conduit to the West Coast modern design boom.

“He basically found a vessel to deliver images – beautiful, well-composed images – that captured the beauty and the pertinence and the integration of the surrounding North Shore region with the architecture in a way that few other photographers could,” Weder says.

Pullan was born in Vancouver in 1922, attended Vancouver Technical School and served in the Canadian Navy during the Second World War. On a veteran’s grant, he studied at the Art Center School in Los Angeles under the instruction of renowned photographer Ansel Adams. Upon his return to Vancouver, he found his niche taking photos of architecture and interior design at a time when mid-century modernism was taking off.

Weder penned an obituary in the October issue of Canadian Architecture that sums up Pullan’s impact and legacy.

“Architectural photographer Selwyn Pullan did not merely document West Coast Modernism; he helped create it. Often thought of as Canada’s answer to Julius Shulman, Pullan created many of the definitive images of the works of John Porter, Ned Pratt, Arthur Erickson, Fred Hollingsworth, Ron Thom, Barry Downs and other giants of the field. In fact, his work helped them to become giants in the first place,” she writes.

Pullan had a knack for seeing buildings from the perspective of the architect. Armed with his signature homemade 4x5 camera, he knew how to capture the natural light, clean lines and wild surroundings that defined West Coast Modernism. His work was in high demand by architectural firms and many of his images were published in popular magazines such as Western Homes & Living, Maclean’s and Architectural Digest.

Local author Eve Lazarus used some of Pullan’s photographs in her book Sensational Vancouver (Anvil Press, 2014). She recalls the first time she visited him at the house he’d lived in since 1952, near the top of Lonsdale Avenue.

“The carport was really fascinating,” she says, explaining that the structure – which reminded her of an airplane – housed a Jaguar under a tarp. As it turns out, Fred Hollingsworth (who also had a penchant for Jaguars) had designed the carport, as well as Pullan’s two-level studio, accessible from his house by a covered passageway.

Lazarus asked how he captured the striking photograph she featured on the back cover of her book, a 1957 image of the BC Electric Building reflecting the sun.

“Uh, that was just a lucky shot,” he told her nonchalantly.

He replied with equal modesty and brevity when she asked him how he approached assignments to shoot houses: “Oh, you know, it was a house. I’d just go photograph it.”

Pullan was the subject of two solo exhibitions at the West Vancouver Museum, which produced the book Selwyn Pullan: Photographing Mid-Century West Coast Modernism (Douglas & McIntyre, 2012). In 2014, Pullan donated his archive of more than 10,000 negatives and prints to the museum.

“I saw Selwyn’s photographs at his studio for the first time in 2004. I kept visiting him to learn about the development of modernism in this city. His images brilliantly showcased modern living on the West Coast and the pioneering architectural designs that played an important role in the city’s growth,” said assistant curator Kiriko Watanabe, in a statement released by the museum.

“We are fortunate that Selwyn chose to donate his collection to the West Vancouver Museum. It is a lasting and historically important record of a bygone era. We will honour Selwyn’s monumental achievements by making the collection accessible over time,” added curator Darrin Morrison.

The West Vancouver Museum plans to honour Pullan’s legacy with an exhibition of his work in 2018.