The underwater forest was brimming.

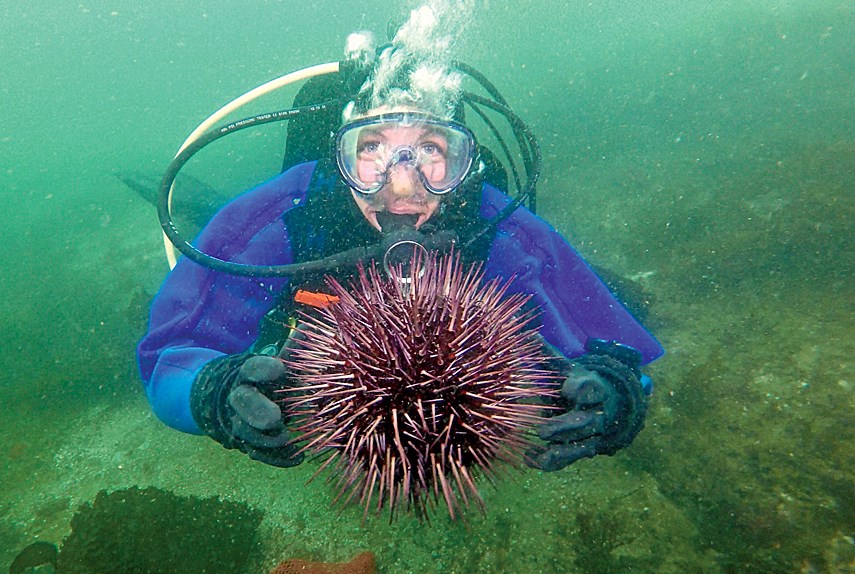

Jenn Burt, decked out in scuba gear and donning numerous scientific instruments, ventured below the ocean’s surface off the chilly B.C. coast with a goal: How is the recovery of sea otter populations affecting other marine ecosystems and nearby coastal communities?

Sea otters, explains Burt, used to occupy all the ocean space “between basically Japan and Mexico” until the decadence of the maritime fur trade all but “eliminated all of the sea otters from the entire B.C. coast” by the time the 20th century came into view.

But something started happening towards the end of the 1960s – the otters started coming back, says Burt.

“They were actually reintroduced actively from some small remaining populations in Alaska to a small area off the west coast of Vancouver Island,” she says. “Since then, the sea otter population has been growing and expanding their population over that space.”

As the sea otter population has slowly recovered throughout the region – they’ll eventually get around to repopulating most of B.C.’s outer coast, according to Burt – several phenomena have been observed. Mainly, that underwater reefs home to sea otters tend to have very low populations of sea urchins – and tons of kelp.

“This understanding that sea otters actually trigger this cascade of events that changes the ocean ecosystem has made them kind of famous as ecological engineers,” says Burt.

While conducting research for her PhD thesis on the topic, Burt spent hundreds of hours underwater among the “luscious kelp forests.” But while she set out to look at how sea otters were affecting certain underwater ecosystems in B.C., she ended up uncovering an even more substantive relationship involving marine life.

While conducting her research near Bella Bella, B.C., Burt made headlines last year for discovering that sea stars – not just otters – also play an important role when it comes to the abundance of underwater kelp, or more accurately, a lack of abundance.

“My contribution was understanding it’s not all about sea otters,” says Burt, noting that sea stars also eat urchins and this in turn has also greatly affected kelp density. The timing of Burt’s discover was fortuitous. In 2015 a case of sea star wasting disease essentially wiped out the entire sunflower sea star population, which led to an explosive increase in the number of small- to medium-sized sea urchins – which are typically ignored by sea otters, who favour the larger, meatier variety – and a huge decline in the density of sea kelp in the area.

“What I discovered was that it’s not just sea otters that contribute to the resilience of kelp forests. Sea stars play a complementary role along with sea otters,” she says. “We saw, therefore, a 30-per-cent decline in the kelp forests when those sea stars went away.”

Burt, who lives in North Vancouver and recently completed her PhD in environmental and resource management at Simon Fraser University, also stresses another major component of her research involved collaborating with local coastal Indigenous communities.

Returning to her sea otter beat, Burt observes that the fuzzy creatures “basically have to eat a third of their body weight every day,” so that means they consume a lot of sea urchins, crabs, clams, mussels and scallops.

“For people it’s a big deal because the sea otters eat all the things that humans like to eat,” says Burt. “In places that sea otters return it also poses major challenges to human populations who like to harvest those species for jobs and also for food …. We have this dichotomy between a conservation win and the recovery of an endangered species, but also the trade off that comes with the recovery of that endangered species.”

Burt was part of the research team that set up Coastal Voices (coastalvoices.net), which brings together a diverse group of Indigenous leaders, scientists and others from throughout the province in order to plan for the profound ecological, economic and social changes triggered by the return of sea otters.

First Nations communities are “basically the primary population that have been impacted by sea otters,” says Burt. “Essentially, they want to play a more primary role in being able to decide how sea otters are managed in their territories.”

Burt took home some hardware along with her diploma after graduating from SFU last month, receiving the Governor General’s Gold Medal award which is given every year to the two graduating students who achieve the highest academic standing in a doctoral or master’s program.

While Burt is already on to her next project as a program lead for an organization devoted to seeking innovative solutions for marine conservation on the B.C. coast, she reflects on her thesis research and how it highlights the interconnectedness between the ocean environment and humans.

“I was trying to both illuminate ecological interactions and implications for humans,” she says. “These things aren’t happening in isolation. We make decisions and those affect the ocean and those changes in the ocean in turn affect us. We constantly need to be understanding these systems as things that we impact – and that impact us.”