This article has been amended since first posting with some minor edits and to include a link to the North Vancouver Museum and Archives online exhibit Through the Lens of Jack Cash: 1939-1970, which can be viewed by clicking here.

The morning is dark as the boy fetches oil to feed the stove in a small house on Western Avenue.

In the winter his job is to bring the firewood delivery from the road to the house by sleigh.

Now see his father. Camera in hand, he is concentrating as he chainsmokes Sportsman cigarettes out of the old yellow pack with the fisherman on the front. His name is Jack Cash.

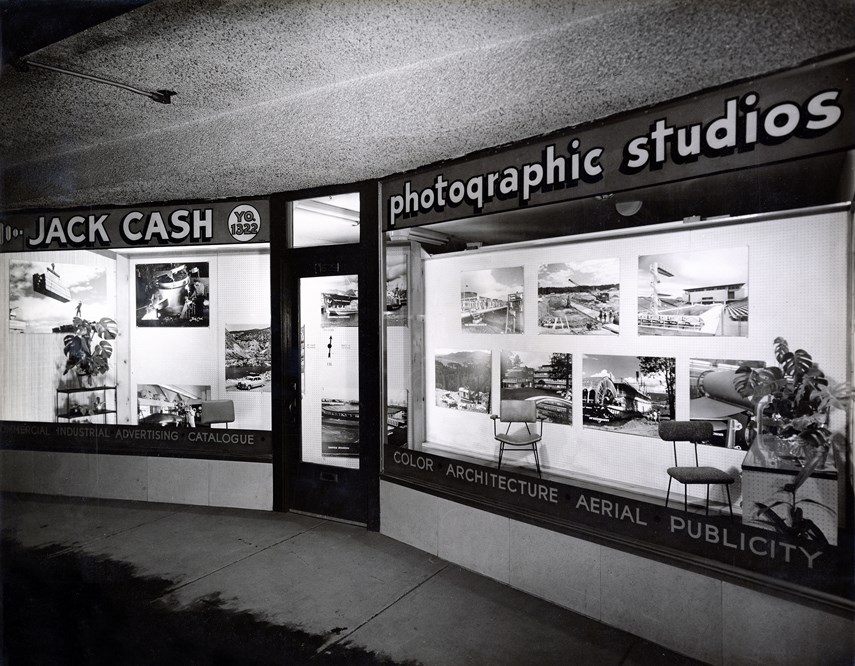

The name hangs over his studio on Marine Drive next to where Capilano Glass is today and it’s splashed across the doors of his 1955 Buick.

Following Jack’s death in 2005, Derek Cash felt a regret shared by many sons.

“I asked very few questions of him,” he says.

Speaking from his home near Seylynn Park, Derek browses his notes for phrases about Jack.

“I was trying to come up with ideas to describe my father,” he says.

Jack was self-taught, Derek reports. An artist with a huge strength of personality.

“Whatever he did he wanted to do well,” he says.

From the onset of the Second World War to the birth of the polyester suit era, Cash established a reputation as North Vancouver’s preeminent industrial photographer. It was a career that started in the footsteps of his mother.

As one of Canada’s first female reporters, Gwen Cash interviewed Emily Carr and chronicled the occultist Brother Twelve in a career that included stints with the Province and Victoria Times-Colonist. Her journalism career was largely the result of being unable to find work as a teacher – as well as some prodding with a hot pitchfork, according to Gwen.

“Urged on by goodness knows what - the devil, likely - I sat down with a thick wad of nice clean paper and a soft-leaded pencil, and wrote pieces about war-embattled England, as I knew it, for the Vancouver dailies," she wrote in an account published by ABC Bookworld.

Jack snapped pictures for the Vancouver Sun during the 1930s before briefly working as an assistant pipe fitter at the Burrard Dry Dock.

“I wasn’t good at being a plumber,” Derek remembers his father saying later.

He didn’t keep the job for long. Following a conversation sadly lost to history, Jack convinced his employer, Wallace Shipyards, to hire him to photograph ships built for the war. They were suitably persuaded and Cash quickly set up a dark room in the pipe shop.

He didn’t make a lot of money but he made enough, Derek remembers.

“We didn’t have any money but we weren’t poor,” he says. “We never did without anything.”

Jack flourished after the war, photographing loggers topping trees, new mills, and construction sites across B.C.

Between 1946 and 1961 he snapped 1,500 photos for MacMillan Bloedel, showing a talent for vistas that capture the collision of nature and industry and – from time to time – his 1955 Buick.

“He sneaks it in there,” archivist Sam Frederick says with a smile.

Frederick curated the exhibition for the North Vancouver Museum and Archives. The building is currently closed. However, portions of the exhibit are slated to be made available online.

Besides the way Cash used colour and shadow to frame his images, his photos are a record of looming changes to the landscape, Frederick explains. They also demonstrate how much he liked his Buick.

If the car wasn’t in the background, it’s likely because he was standing on the roof to get a better angle. He only fell off once, Derek reports.

“Fortunately he only shattered the windshield,” he says.

By the end of the 1950s, Cash had moved his family into an $22,000 house on St. Georges Avenue. The home had a thermostat, Derek notes.

“That was a luxury,” he chuckles.

He remembers his father piloting the Buick and picking up messages with a radio telephone he kept in a “great big box” in the trunk. Derek also remembers the days when bigger stores started selling cheaper cameras to confused consumers who would eventually take their purchase to Jack and ask: “How do you work it?”

“That drove him crazy,” Derek recalls. “I don’t think he turned them down but he wasn’t happy doing it.”

Jack eventually closed the shop after a partner “ran it into the ground,” Derek says.

Following the closure, Derek took it upon himself to save the photos, records, cameras and the Jack Cash cigarette lighters his father handed out as a promotional tool. He’s had some of it for 46 years, preserving the pieces of history through moves and floods.

“I can’t throw that away,” he remembers saying. “Someday, somebody’s going to want that.”

The exhibition is an affirmation, Derek says.

“I feel very proud,” he says. “Grateful.”

Jack moved to a new career taking passengers up and down the coast in his charter ship, The Columbian, which was built at Burrard Dry Dock in 1956.

He was happy doing it, Derek says.

“Boating and fishing was a passion and a pleasure. I guess the photography was more work – and an art form.”

Jack eventually quit smoking upon retirement, Derek notes, becoming “very self-righteous about ‘these damn smokers.'”