There was once a time, not all that long ago, when Marcus Wong wouldn’t have been welcome in his own home.

It was written right into the land title document registered with the province at the time his neighbourhood in the British Properties was under development.

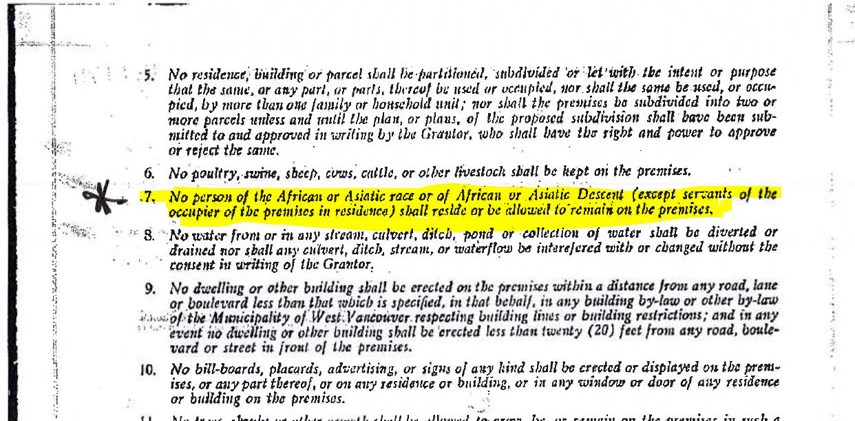

“No person of the African or Asiatic race or African of Asiatic descent (except servants of the occupier of the premises in residence) shall reside or be allowed to remain on the premises,” the covenant reads.

The covenant came standard with new homes built in the first phases of the British Properties.

But Wong isn’t having it, and nor should any other person who buys a home there, he said. Wong will be introducing a motion Monday night, asking district staff to work with their lawyers and with the Land Title and Survey Authority to “determine the process, resources and time required to achieve the cancellation and striking of discriminating covenants” in the British Properties.

“I thought it was really important to clear the slate, shall we say, for British Properties and West Vancouver – to say this is a community where everybody’s welcome, regardless of what your background is, whether you’re a new Canadian, whether you’ve been here for many generations,” he said. “Given the fact that I’m the first non-Caucasian member of council in West Vancouver, I thought it was especially important for me to make this gesture.”

Excluding buyers based on race was by no means exclusive to the British Properties. Homeowners in Edgemont, Upper Capilano, Shaughnessy, Kerrisdale and Westmount may find the effective “whites only” rules on their land titles.

Changes in B.C. laws in the 1970s made any discriminatory covenant of no force and effect, but for Wong, that’s not enough.

“To have a home where you live and land title that says you’re not welcome, because of the colour your skin, that’s just not right,” said Wong, whose parents came from Hong Kong in their teens.

Coun. Craig Cameron has signed on to second Wong’s motion, saying no one who buys a home in West Van should have to see the discriminatory clause.

“I think it is offensive, and it’s something that we need to send a strong message that this isn’t the kind of society we are anymore,” he said. “Just like we would scrub off racist graffiti on the side of a building, we want to scrub these titles of their racist overtones.”

In 1978, the Land Title and Survey Authority set a policy that it would remove discriminatory covenants from land titles at an owner’s request without charging the typical fees.

Such requests, though, are “once in a blue moon,” said Susan Wells, director of communications for LTSA.

Since most people don’t even know if their property has one, finding out may require hiring a registry agent to search the old microfilms on which old land titles are physically stored in New Westminster.

And depending on the way the land title is written and the number of covenants on it, it could be more complicated. In some cases, even requiring a court order, Wells said.

With more than two million active titles in B.C., Wells said there is no way of knowing how many properties still have the offensive terms attached to them.

No one from British Pacific Properties agreed to an interview but company president Geoff Croll issued a statement.

“British Pacific Properties fully supports Coun. Wong’s motion, and any other steps taken by the District of West Vancouver, to remove discriminatory language from the titles of properties located in the district,” it read. “These offensive, restrictive covenants are found on properties throughout the province, including [in] Vancouver, Victoria, and North and West Vancouver, and although they are void and unenforceable, they have no place in our society.”

While his motion names British Properties specifically, Wong said if anyone else knows they have the covenant on their home elsewhere, he’d like to know about it to aid staff in their work.

UBC history professor Henry Yu said covenants aren’t so much a shameful quirk of history, but rather a natural extension of the racist ideals British Columbia was founded on.

After clearing Indigenous people from their land in the name of the Crown, one of the first acts of government was establishing a rule barring non-whites from voting.

“And from that moment on, things like housing covenants are just parts of the myriad ways at the municipal level, provincial level and federal level that you have the legalized power of the state, behind white supremacy,” he said.

While they inspire disgust now, Yu noted the covenants were used to help market the properties to prospective buyers.

“It’s not a coincidence or an accident or some freakish aberration. It is the thing you’re selling,” he said. “They were white neighbourhoods. Chinese were OK as long as you are a servant. You are like Harry Potter under the staircase.”

But Yu, who has advised the City of Vancouver and the province on their apologies for past discriminatory policies, said West Vancouver needs to be very careful about how it approaches the racist land title issue.

If it’s done quickly and quietly without any effort to publicly confront the racist context in which they were written, then he’d rather they stay in the historical documents.

“If you just want to clean it, then I actually think that’s exactly what we’ve been doing for 100 years,” he said, noting most people who own homes with the covenants don’t even know it. “You’re actually just making it worse. You’re erasing the evidence. It’s like doing a coverup, so don’t do that.”

If done well though, it could be the start of a long overdue conversation that West Vancouver needs to have, he said.

“I’d like that to be actually a fairly robust process that leads to a better awareness that [racist covenants] were there. ... The city should also undertake to map all the ones they find, share it publicly and talk about it and reckon with it,” he said.