Traffic gridlock is seriously impacting North Shore businesses, but there’s no magic bullet solution, said speakers at a transportation forum Wednesday.

“Transportation is the No. 1 economic issue in North Vancouver,” said Patrick Stafford-Smith, CEO of the North Vancouver Chamber of Commerce.

Much of that traffic is created by people who work on the North Shore but live elsewhere, said speakers.

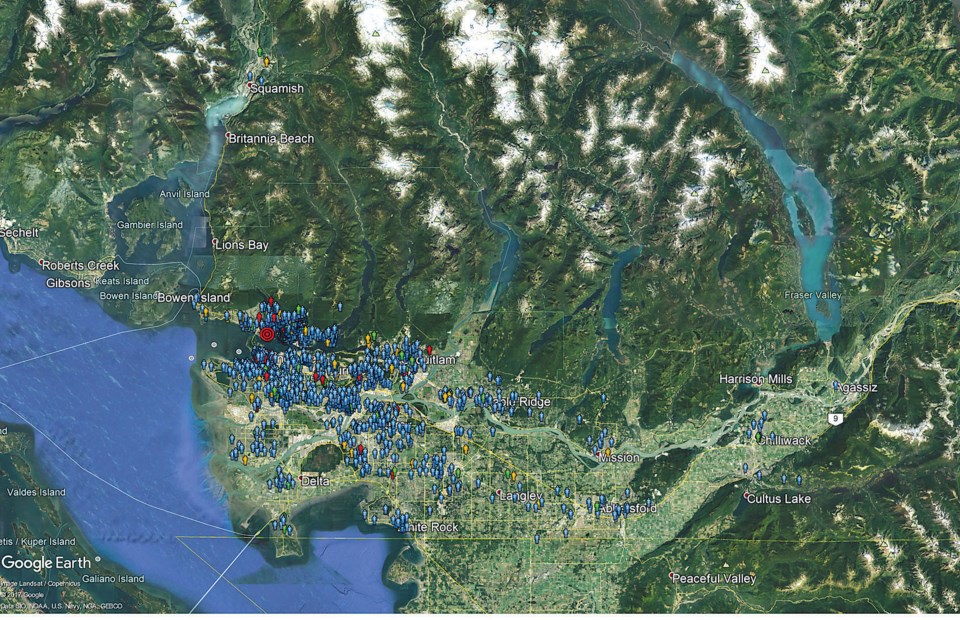

To demonstrate commuting patterns, Stafford-Smith showed a recently created map with blue dots representing where workers of four representative North Shore employers live, scattered throughout the Lower Mainland, ranging from Squamish to White Rock and out into the Fraser Valley.

“This is not just contractors,” he said. “It’s white collar, blue collar.”

The forum, attended by business leaders and politicians Wednesday morning, was hosted by the chamber and its economic partnership at Capilano University’s Bosa Centre.

As both an educational institution and a major North Shore employer, transportation is a significant issue for Capilano University, said Toran Savjord, vice-president of strategic planning for the university.

Kevin Desmond, chief executive officer for TransLink, said congestion is a problem throughout the Lower Mainland, but “we need to dig further into the data” to find out more about how people and goods are moving around the region. One thing that’s clear is more people are commuting to the North Shore for work now than away from it.

In the decade between 2005 and 2016, the volume of traffic heading south over the Ironworkers Memorial Second Narrows Crossing remained steady, said Desmond, while the volume of cars heading to the North Shore in the morning increased between 10 and 12 per cent.

That’s despite a recent increase in ridership of between two and seven per cent on buses heading over the bridges and a seven per cent increase in SeaBus boardings in the past year, said Desmond.

Meanwhile the Lions Gate and Second Narrows bridges still have the same combined nine lanes they were built with to absorb the extra traffic, he said.

Two North Vancouver employers described the transportation challenges they’ve faced getting employees to their work sites.

Seaspan has added more than 1,000 employees to its workforce in recent years and 75 per cent of them don’t live on the North Shore, said France Buzelaar, chief executive officer. While the company has had success promoting carpooling and has been talking to TransLink about developing van pools, the shipyard at the base of Pemberton Avenue is not on any bus routes, he said, so many of the 1,300 workers on day shift there in North Vancouver have “very few options other than to commute by vehicle. By and large our people are driving to the North Shore every morning.”

Lance Richardson, vice-president of operations at Arc’teryx Equipment, said his company’s 450 North Vancouver employees face similar challenges.

About 75 per cent of those workers don’t live in North Vancouver, said Richardson, whether that’s because of housing affordability or other lifestyle factors like where an employee’s spouse works.

“There are too many days recently when people are in the coffee room wasting time complaining about the traffic mess,” he said. But the alternatives in getting to the head office on the Dollarton Highway aren’t great, he added. “It’s taking people an average of 55 minutes to get to the office by bus,” he said. “That’s a lot of commuting time.”

Desmond said every area of the Lower Mainland wants more transit. “Big ideas” – like bringing a SkyTrain to the North Shore by tunnel, floated by North Vancouver City Mayor Darrell Mussatto, or building a rapid transit line here, put forward by North Vancouver-Seymour MLA Jane Thornthwaite – get a lot of buzz in the media, said Desmond. “People really want to think big,” he said. “Thinking big comes with a price tag and a time dimension. That tunnel – you’re talking billions of dollars and years and years of development.”

While big ideas are welcome, “We also have to be thinking of today and tomorrow, let along the day after tomorrow,” he said.

Buses are viewed as “second best,” he said, but if there’s a good bus system, people will choose it. TransLink plans to have an east-west B-line bus running across the North Shore in place by 2019, along with a third SeaBus running on 10-minute intervals.

Desmond said other options like van pools, car sharing and ride hailing could all be part of the congestion solution.

Dr. Anthony Perl, a Simon Fraser University professor of urban studies who has examined transportation, echoed many of those comments.

“Everyone wants rapid transit,” he said. “Rail is seen as the gold standard.”

But at the same time, “Those same people hate to pay for the taxes and tolls” which pay for that expensive transit infrastructure, he said.

“We love the benefits of mobility but we hate to pay for them.”

Perl said that mindset was evident in the 2015 referendum on TransLink funding that was defeated by voters.

“It can be very risky for public officials to (ask the public to) pay now and get something later,” he said.

Similarly, most people think the onus is on someone else to solve the gridlock problem, he said, imagining, “if the other person who is beside me hogging this road were to disappear on to a bus that would automatically solve the problem.” But “it’s not just about getting someone else to do something,” he said.

“We’re all in it together.”