If you want to find a gym or a bank in North Vancouver, you’ll have no trouble finding one by walking down the street.

But a quirky independent dress shop, a print store or artisan bakery?

You’ll likely have to look a little harder.

That’s because commercial assessments that keep rising even as residential values are falling mean many smaller local businesses are facing pressures to stay afloat on the North Shore.

The types of leases most businesses have to sign –requiring them to pay any increase in property tax tied to those assessments –are proving too much for some, causing independent shops to close and be replaced with financial institutions, chain stores and medical offices –among the few who can afford the rent.

“Edgemont has five banks,”said District of North Vancouver Coun. Lisa Muri, who has voiced concern for the past several years about costs driving out local businesses. “It’s three blocks long.”

“In the past, [commercial areas] were such an eclectic mix,”she said.

But that colourful mix of mom-and-pop style of business is buckling under pressure.

Patrick Stafford-Smith, CEO of the North Vancouver Chamber, shares those concerns.

“I’m really concerned about losing businesses that have been valuable to the community,”he said. “They are pushed out because of factors out of their control. We are seeing businesses leave.”

As a commercial real estate agent who specializes on the North Shore, Ross Forman has a front-row seat on many of those changes.

“I think retailers in general are struggling,”he said.

“Just before Christmas I think we had six retail vacancies come up in the Lower Lonsdale area. We usually have maybe one or two at a time.”

Overall in North Vancouver, commercial assessments this year are up between two and seven per cent while light industrial properties are up between nine and 18 per cent.

But that’s on top of stratospheric rises last year of 21 per cent for commercial properties and 27 per cent for light industrial properties on the North Shore last year.

And some increases in assessment have been far higher. Forman said one property owner of a two-storey industrial building on East Esplanade has seen his assessment jump 34 per cent this year. Another owner of buildings in the Pemberton and Welch light industrial area has seen her commercial assessment jump over 40 per cent.

With relatively few sales of commercial and industrial land, it only takes a couple of high-priced transactions to set the market ticking upwards.

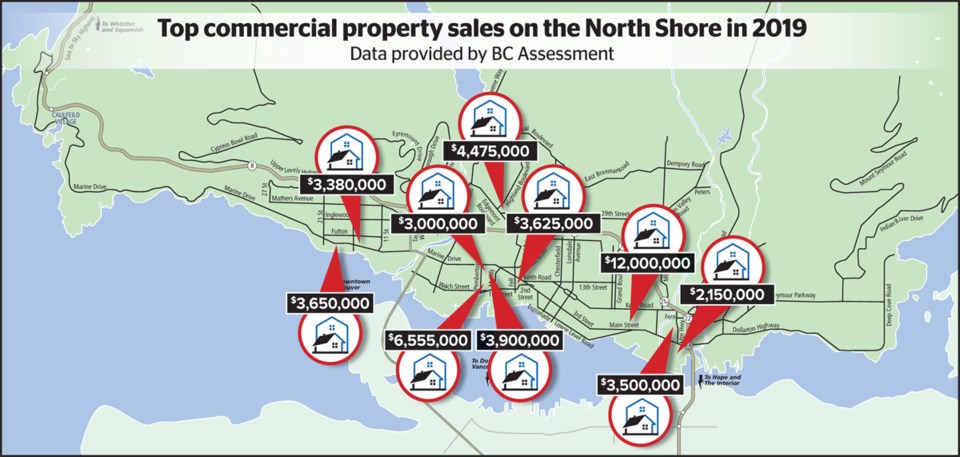

One of the biggest transactions last year in North Vancouver was the sale of the longstanding Windsor Plywood property at 309 Kennard Ave., along Cotton Road.

Four years ago, that property with a single-storey 1960s warehouse was assessed at $3.66 million. It sold in February for $12 million.

Another 15,000-square-foot property in the commercial and light industrial area near Pemberton sold for $6.55 million last year –over twice its assessed value just four years ago.

Forman points to another commercial property at 266 East First St. with just over 3,600 square feet that sold for $3.3 million at the end of 2018.

“A brewery bought it,”said Forman. “That’s $911 a square foot. That is probably $200 a square foot higher than what it should have sold for.”

“When you get two or three sales like that in that price range, that’s where it starts to affect where the market sits.”

In the world of residential real estate, when an assessment rises much faster than the average, it’s the property owner who ends up footing the bill for increased taxes.

But in commercial real estate, it’s different.

Not so long ago, “there were lots of gross leases,”said Forman – in which costs like property tax were included in the price.

But in the past decade especially, that’s changed to something called a “triple net” lease, in which additional costs like property tax are paid by the tenant.

“Ninety-five per cent of the leases are all triple net leases,”said Forman.

“Which means that if the property taxes go up, it just automatically falls on the tenant. The tenant has to pay the bill.”

If assessed value suddenly skyrockets, that could see a small business forking out an extra $1,500 a month, just in tax increases.

“I’ve had merchants tell me the taxes are substantial for them,” said City of North Vancouver Coun. Don Bell, who has raised concerns about the issue.

“They’re struggling. They’re competing with big box stores and the internet. This is the straw that is breaking the camel’s back.”

Exacerbating the problem is the way properties are valued by BC Assessment on their “highest and best use.”

Under that system, properties aren’t assessed on their current use but on the potential value of what the property would be worth if it was redeveloped to the maximum density allowed.

That’s how aging one- and two-storey retail buildings get assessed as though a mixed-use highrise is already standing on the site.

Buildings in Lower Lonsdale, lower Capilano and lower Mountain Highway are among those recently impacted.

That’s also what happened at Westview Shopping Centre last year, said Forman, when the property assessment jumped 43 per cent in value – from about $40 million to roughly $57.5 million.

“The assessment authority went in and said, ‘You know what? It’s time that this is a redevelopment property. We’re going to base it on highest and best use that says you can put towers on it,’”said Forman. But in the meantime, “We have leases that go till 2032. So they’re paying higher taxes for the next 12 years.”

Alarmed by the number of local businesses who can no longer make it in an environment of skyrocketing assessments, local politicians have lobbied the province to change the way commercial properties are valued.

In the last week, the province has indicated it’s working on a fix, although the details of that are still scant and it’s possible it may create as many problems as it solves.

According to the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing, legislation will be introduced this spring that would give municipalities the ability to provide a tax break to small businesses they identify as paying high property taxes.

The interim legislation would allow municipalities to exempt a portion of the value of some commercial properties from taxation, according to the ministry.

But exactly how that would work is raising another set of questions.

“The devil is really in the details,”said City of North Vancouver Mayor Linda Buchanan when city council discussed the issue Monday night. “There’s a lot of unanswered questions. Some people think it’s easy to do tax policy. It’s not.”

Making municipalities choose which properties qualify for a tax break and which don’t could easily lead to friction as businesses lobby town hall for exemptions, said Stafford-Smith.

“I think it’s going to be a nightmare,”said Derek Holloway, a recently retired BC Assessment assessor. “I think what will happen is it’ll put the municipalities in the position of playing favourites – the pie shop versus the car dealership.”

It also isn’t clear yet whether the tax break would apply just to rented properties or also to those which are owner occupied.

“To fix it, it may create even more problems,” he said.

Chief among those is that municipalities still need to collect the same amount of tax revenue, regardless of who’s paying.

And if some businesses are paying less, inevitably someone else is paying more. “Somebody pays eventually,” said Holloway.

Pete Turcotte, owner of Big Pete’s Collectibles, has experienced first hand the stresses that rising assessments and taxes can bring during his 29 years in business in Lower Lonsdale.

In his last location in the 100 block of Lonsdale, Turcotte had what he felt was a “very fair” gross lease for his shop. “We were paying $5,300 a month,”said Turcotte. But when it was time to renew, his landlord wanted to increase that to more than $8,000 a month, he said. His counter-offer – of more than $7,000 – was rejected.

Turcotte had no choice but to move to a smaller nearby location at 121 East First St.

He considers himself lucky to have found a landlord who wanted a stable tenant.

This time, though, the lease is triple net.

Turcotte said he questions whether anyone should be asked to pay the taxes for their landlord.

“There just comes a point when landlords shouldn’t expect tenants to cover everything,”he said. “If you’re going to own a building, maybe you should be on the hook for that increase in value yourself. It’s win-win for them and lose-lose for us.”

But most businesses don’t have a choice. Whether it’s space in an old building with a rising assessment or space in a newer and more expensive building “there isn’t a better option,”said Turcotte. “It just gets more expensive.”

Meanwhile his old space on Lonsdale is still sitting empty – something that’s happening more frequently as local businesses are forced out.

Turcotte questions whether government could help with rules that ground floor properties must be retail – not occupied by services. He also wonders why there’s no provincial vacancy tax on commercial units – something he suggests might prompt landlords to set more reasonable rents.

Empty retail space left by vacating local business don’t help anyone, he said. “There’s no businesses in it. There’s no employees in it. They’re not doing anyone any good.”