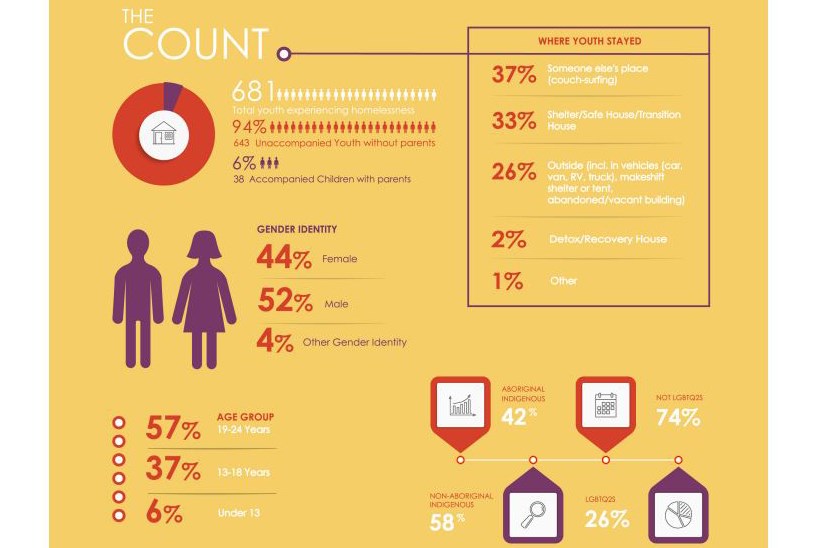

At least 681 youth were homeless in Metro Vancouver in April.

That number was found during the first-ever count of homeless people aged 13 to 24 in the region. The Youth Homelessness Count, released Thursday, was conducted by the BC Non-Profit Housing Association on behalf of Metro Vancouver (regional district).

The count used a different methodology than the general homeless counts conducted every three years. Rather than have volunteers fan out across Lower Mainland cities, counters surveyed young people at youth centres, high schools and shelters, as well as collecting statistics from service providers.

This approach allowed the team to find a more accurate number, “because we know that youth are often part of a hidden population,” said Lorraine Copas, chair of the Metro Vancouver Homelessness Partnering Strategy community advisory board.

The majority of respondents (74 per cent) were couch surfing or staying in a shelter, transition home, detox centre or recovery house.

Most of the 681 youths were living in one of three Metro Vancouver areas: Vancouver (349), Surrey (106) or the North Shore (64). But Copas said there is likely more of an undercount in cities, such as Burnaby, where there are fewer service providers able to connect with homeless youth.

- Burnaby: 34

- Delta: 16

- New Westminster: 33

- Richmond: 18

- Tri-Cities: 20

“The count shows that Indigenous people continue to be disproportionately affected by homelessness,” said Joanne Mill, executive director of the Fraser Region Aboriginal Friendship Centre Association, in a press release. “We’re starting to get a clearer picture of the unique struggles facing young people.”

Mills said the count “is a step in the right direction to figuring out how we can tackle homelessness across the region.”

Youth who identified as lesbian, gay, transgender, queer or two-spirit accounted for 26 per cent of those counted.

Copas said there are a myriad of situations that lead to a young person finding themselves without a stable home, but family breakdowns and youth aging out of care are very prevalent among the population surveyed.

More than half of the youth said “family breakdown” led to their homelessness.

Most surveyed said they had been in the foster care system at some point.

The report recommended raising the age at which youth age out of care (currently 19).

“In a traditional family, many families would still have their kids staying at home at age 19, 20, 21, 22 – they would be fully supported,” Copas said. “And so what is it about a youth in the foster care system that’s ready for full independence at age 19? And what's that look like in a market where there is no housing, where you can't produce a landlord reference, where the rents are so high?

“It's a vicious cycle.”

Copas said there has been no indication the provincial government will raise the age.

“I think there's awareness, but there hasn't been movement,” she said.

Copas also highlighted the fact that nearly one in five youth in the survey said they were employed at the time. She said this is an important reminder that “they're doing the best that they can with what they've been given and I think, as a society, part of our role is to help any youth realize their full potential.”

“Once you hear that people have a full-time or part-time job and they're doing their best but they still can't get in, you start to realize that is a true sign of system failure because some things aren't working.”