MONTREAL — Canadian Indigenous leaders say U.S. President Joe Biden’s apology for his country’s residential school system is only the first step toward healing generations of harm.

On Friday, Biden apologized for the U.S. boarding school system that for more than 150 years separated Indigenous children from their parents, calling it “one of the most consequential things” he’s done as president.

The apology comes 16 years after former prime minister Stephen Harper apologized for Canada’s residential school system. It follows an investigation of boarding schools driven by U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, the country’s first Indigenous cabinet secretary, which was prompted by the discovery of 215 suspected unmarked graves at a residential school site in Kamloops, B.C.

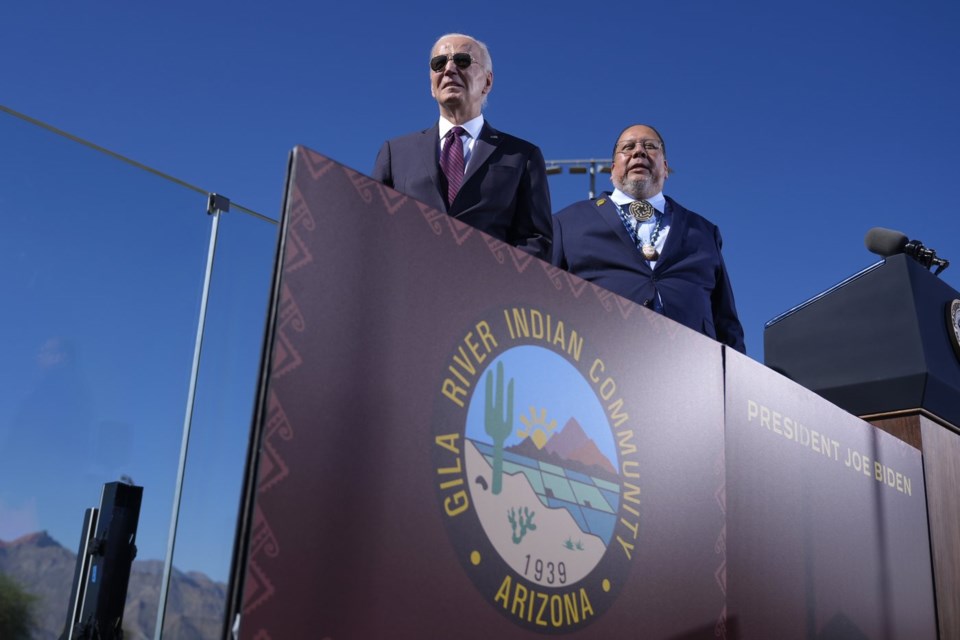

“The federal Indian boarding school policy and the pain it has caused will always be a significant mark of shame, a blot on American history,” Biden said during a speech at the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona. “It’s horribly, horribly wrong. It’s a sin on our soul.”

Former Assembly of First Nations national chief Phil Fontaine, who was one of the first Canadians to speak publicly about the abuse he experienced at a residential school, said Canada has had “tremendous influence” on the U.S. starting to reckon with its own history.

“The U.S. government could no longer turn a blind eye to the boarding school experience in the United States,” he said. “And they ultimately decided that this was the right thing to do, and it certainly is.”

In 2021, Haaland launched an investigation that found at least 973 Native American children died in the U.S. boarding school system, including from disease and abuse. On Friday, Biden acknowledged the true number is probably “much, much higher.”

The U.S. government implemented a forced assimilation policy in 1819 as an effort to “civilize” Native Americans. For more than 150 years, Indigenous children were forced to attend the schools, many of which were run by churches. Many children were physically, emotionally and sexually abused.

The investigation found marked and unmarked graves at 65 of the more than 400 boarding schools across the country. Haaland, whose grandparents attended boarding school, led listening sessions over two years on and off reservations across the United States to allow survivors of the schools to tell their stories.

When the findings were published last summer, Haaland said there should be a formal apology from the federal government.

“For decades, this terrible chapter was hidden from our history books,” Haaland said in Arizona on Friday. “But now, our administration’s work will ensure that no one will ever forget.”

Fontaine said the United States should now launch its own truth and reconciliation commission, as Canada did in 2008, and should look at compensating residential school survivors. There is currently a bill pending before Congress that would establish a “truth and healing commission” to further document the history of the boarding schools and to make recommendations for government action.

Assembly of First Nations National Chief Cindy Woodhouse Nepinak said the history of U.S. boarding schools echoes the experiences of First Nations in Canada.

"The impacts of these schools have affected generations," Woodhouse Nepinak said in an emailed statement. "This acknowledgment is important, but healing will take time. I urge President Biden, and the incoming president-elect after next month’s election, to engage meaningfully with Native American communities and ensure that this apology leads to real actions that address the harm caused."

On Friday, Biden said the “vast majority” of Americans are still unaware of what he called “one of the most horrific chapters in American history.”

That was also the case in Canada before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission gave survivors an opportunity to share their experiences, Fontaine said. In 2015, the commission released a final report that concluded the residential school system amounted to cultural genocide. In total, 150,000 Indigenous children were removed from their families to attend Canadian residential schools, the last of which closed in 1996.

“It was a dark chapter, unknown to most Canadians, but it’s become very much part of Canadian history that’s been exposed to more Canadians than ever before,” Fontaine said. “And I believe that’s entirely possible in the U.S. as well.”

But Eva Jewell, an assistant professor of sociology at Toronto Metropolitan University and research director at the Yellowhead Institute, believes it will take a long time for the United States to achieve a “national understanding” of the boarding school system.

“The political culture in the United States is very hostile to any kind of justice-oriented education,” she said. “So I think where it does happen, it will probably be in fairly progressive states.” Jewell said a belief in American exceptionalism could explain why the apology took so long. “I think U.S. political culture has a very unapologetic stance on its history,” she said.

Stephanie Scott, executive director of Canada’s National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, said Biden’s apology is positive, but “only a first step.”

“There is a long road ahead to address the ongoing harms, reparations, and continuous revelations of truth to achieve reconciliation,” she said in a statement, adding that Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission can serve as a model for other countries.

The commission’s 2015 report documents how Canada’s residential school system drew inspiration from the United States. In 1879, lawyer and journalist Nicholas Davin authored a report on American industrial boarding schools for Indigenous children and recommended that Canada create a similar system.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Oct. 26, 2024.

— With files from The Associated Press

Maura Forrest, The Canadian Press