Few interview subjects I’ve encountered over the years have arrived with the instant vitality that Grant Connell hit me with when I met him at a North Vancouver coffee shop in early February.

The wildest part of the interview, in fact, was that he didn’t actually order a coffee, because from the moment that Connell sat down with me until we said our goodbyes some 40 minutes later, the former tennis star held court like a delightfully over-caffeinated raconteur.

Which is why I was so shocked when, just a few weeks later, I got a call from Grant’s dad, Jim, telling me that Grant, just 54 years old and a father of five kids between the ages of 12 and 21, had suffered a stroke and was in hospital, faced with a long recovery with an uncertain conclusion.

The occasion of the coffee shop interview was Connell’s inclusion as one of five athletes and one team heading into the North Shore Sports Hall of Fame, class of 2020. It’s lovely to be recognized with a call to another Hall of Fame, Connell said, a brief acknowledgment of the honour coming between wildly entertaining stories about life on the professional tennis tour.

There was the story about the time he was a last-minute entry in a pro-am doubles tournament at the Beverly Hills Tennis Club, called in to replace Vitas Gerulaitis after Gerulaitis tragically died in a carbon monoxide poisoning accident. When Grant arrived at the club he noted that it said “Connell/Hoffman” on the tournament board.

“My partner for this three-day event was Dustin Hoffman,” he said. “And he’s a tennis nut. We would warm up for an hour every day, then we’d play our match, then I’d have dinner with him and his wife at the House Of Blues. And we won the tournament, and he was ecstatic.”

And then there was the time he inadvertently offended the legend, John McEnroe.

“He and I did not hit it off. I don’t know why. Well, I kind of know why,” he said with a laugh. “He was on the comeback trail and he beat me two times in a row in singles. I was at a cocktail party – you have to do these cocktail parties when you’re on tour – and I didn’t know he was in the room. You have to introduce yourself, so I said ‘Hi, I’m Grant Connell, I’m from Vancouver and I’m a tournament director’s dream player, because I’m the only person losing to McEnroe these days.”

And there was the time track and field star and fellow North Shore resident Charmaine Crooks cussed him out at the Olympic Games.

“She yelled at me once at the Seoul Olympics because we were making too much noise playing football in the courtyards,” he said. “We’ve been friends ever since.”

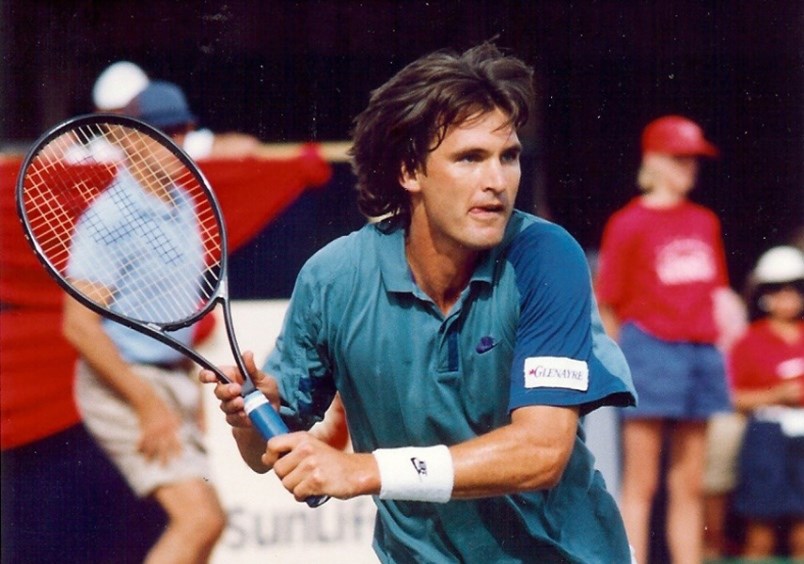

Connell was a pro for 12 years, reaching No. 1 in the world doubles rankings and No. 67 in the world singles rankings, despite not taking up the sport until he was 14. He was a natural. Within a year and a half he was No. 1 in B.C., and then a year later a national junior champion in singles and doubles.

The tennis and celebrity stories flowed out of him with folksy flair, but he really lit up when talking about his family, his wife Sarah and their five kids. In fact, less than a minute after sitting down for an interview about his tennis career, the proud papa pulled out his phone to show a video of his son playing hockey. And of course it was no ordinary video, but rather his son, a high level player in the BCHL, getting into a fight with the son of former NHL player Doug Weight.

“First fight,” Grant said. “Doug Weight’s kid asked him – he didn’t even want to do it. … He probably won’t fight again.”

Grant beamed as he talked about his son earning an NCAA hockey scholarship, gushed about his eldest daughter’s field hockey exploits at Stanford, laughed about taking his three younger daughters, including a set of twins, to the B.C. Sports Hall of Fame only to find that the evidence of his inclusion in that hall was hidden behind a bookcase.

He softened even more when talking about his own parents, Jim and Pat, and how they supported his career while also providing the blueprint he now follows as a dad.

“They sacrificed a lot. I didn’t see that then, but I understand now what they did,” he said. “I was a swimmer. I put them through it every weekend. Richmond, Coquitlam, outdoor pools, standing around for one 40-second race the whole weekend. And then the poor bastards, I got into tennis and now we’re going to Bellingham, Tacoma, Yakima – I played all over the Pacific Northwest. They’re driving me. Other guys who were better than me might not have had parents who were as smart.”

This week I chatted again with Grant, who after tennis became a successful Realtor on the North Shore. He’s currently in Vancouver’s GF Strong Rehabilitation Centre where he will likely stay until at least May. His wife is allowed to visit him as his certified assistant but no one else can anymore due to COVID-19 restrictions, so he’s settled on driving the staff crazy.

“I have to stop making those stupid references that I do … they’re threatening to put me on Ritalin,” he said with a laugh following an off-colour joke about social isolation and having a paralyzed hand. “I’ve got to play it straight and narrow. Not many people get my humour here.”

The stroke paralyzed his left side, but didn’t do anything to dull his wits, or wit.

“As John Lennon said, I’m just watching the wheels go round and round. But I guess everybody is, so that’s a small consolation.”

It’s jarring to picture Grant – the natural athlete, the fountain of energy, the father of five – fighting hard just to stand up and take a few short steps. His leg movement is coming back on the left side, but his left arm, hand and ankle are slow to respond – tough news for a man with a famous left-handed tennis stroke.

“I don’t know if I’m ever going to be able to grip again. I’m going to fight like a banshee to get through it. ... I’m in a bind now but will beat this,” he said, adding that he’s been contacted by everyone from his old partners like Patrick Galbraith and Glenn Michibata to friends from elementary school to old coaches and training mates from his junior days at the North Shore Winter Club. Friends have set up a food rotation to help keep his family fed, and before the quarantine his room was always crowded with visitors.

“I get so choked up even talking about my community,” he said. “They take care of my family. People are volunteering to bring meals to my family. It just helps me so much. I’ve always been a huge guy about community, I try to live my life that way. It’s so humbling and touching to see this great community that I live in – it’s not easy to reach out to a former athlete who is now mangled. It’s awkward for people.”

But they are reaching out, helping to pick him up while he is down.

“I’m so fortunate,” he said. “I’m not a religious man, but I am blessed to have such a great community. My biggest concern is how I thank everybody.”