If a major earthquake hit the North Shore today, many buildings in several low-lying waterfront areas would likely topple as sandy soils were subject to liquefaction. Landslides would likely be triggered along escarpments of the Capilano, Lynn and Seymour rivers.

Older neighbourhoods of Norgate, Pemberton Heights, Highlands, Edgemont, Lower Lynn and Riverside would likely see pockets of extensive residential damage.

As many as 15,000 homes would be without water and power and over 4,000 people could be forced out of their homes in the immediate aftermath of a large earthquake.

Up to 2,000 people are likely to be injured, several hundred of those seriously, overwhelming Lions Gate Hospital and other local medical facilities. Several hundred would likely be critically injured, or killed.

Other areas of the Lower Mainland — some of them worse hit — would also likely be too busy dealing with their own immediate needs to offer much assistance.

Those sobering pieces of information aren’t just guesses. On Monday, the District of North Vancouver released the results of a detailed five-year study that models earthquake risk in the municipality.

The study, conducted by experts at the Earth Sciences section of Natural Resources Canada and the University of British Columbia, is the most detailed assessment of its type ever conducted in Canada. (To read a shorter, plain language version of the report, When The Ground Shakes, scroll to the end of this story.)

As the release of the report was prepared last week, none of those involved knew that it would end up happening just days after a deadly earthquake struck Nepal, focusing attention on the issue.

Murray Journeay, research scientist at the Geological Survey of Canada, said the study was designed to answer the question “What If?” a major earthquake hit an urban centre on the west coast.

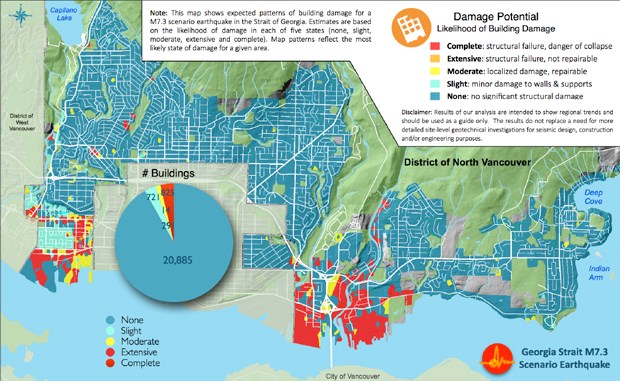

The study models a shallow 7.3 magnitude earthquake with an epicentre in the Strait of Georgia. That’s not the worst-case scenario, says Journeay, but it is scientifically plausible, carrying a 12 per cent chance of occurring in 50 years. It’s similar to the 6.3 magnitude earthquake that hit Christchurch, New Zealand in 2011.

In the study, scientists examined the likely effect ground shaking would have on different types of soils mapped in the district, and then factored in types of building construction, their ability to withstand earthquakes and what kind of populations might be most effected.

The good news is that the majority of people in the District of North Vancouver live in wood frame houses, which are inherently better able to withstand earthquake damage and most are built on stable, solid ground. That would be especially important if an earthquake struck at night, when most people are home.

Over 90 per cent of buildings in the district are expected to escape with only slight or moderate damage, despite the fact that almost 70 per cent of those buildings were built prior to modern seismic standards.

“Probably our community is in as good a shape as any in Metro Vancouver,” said District of North Vancouver Mayor Richard Walton.

The bad news is areas likely to be most impacted by ground shaking and soil failure in an earthquake — low-lying waterfront areas and river escarpments — are also where a lot of older buildings more likely to be damaged are located. According to the study, about 840 buildings would likely be extensively damaged or collapse completely if an earthquake hit.

Many of those are un-reinforced masonry buildings or concrete buildings built prior to the mid-1970s.

Many of those buildings are commercial or industrial buildings near the waterfront. Damage there would have a large economic ripple effect in the community, the authors note, with large parts of the business district “cordoned off for up to a year or more during the recovery and rebuilding process.”

Some municipal buildings — including one firehall — and some daycares and facilities that care for the elderly in the Lower Lynn and Norgate areas are other hotspots of concern noted in the report.

Direct economic losses of such an earthquake striking the district are estimated at $3 billion.

The report isn’t intended to scare people, said Fiona Dercole, manager of public safety with the district, but it is meant to prompt conversation and to make a start towards mitigating risks.

The hazard is there, said Dercole, whether people choose to talk about it or not.

Walton said the municipality has wrestled in the past with question of how much to make public — starting when it completed a landslide risk assessment following a fatal landslide in 2005. He added the district has opted for openness.

One of the most telling parts of the study happened when researchers re-ran their earthquake model — this time with the assumption buildings had received seismic upgrades.

Under that scenario, the 840 buildings damaged beyond repair was reduced to 21. Upgrading buildings would also cut deaths and critical injuries by 50 and prevent 100 more serious injuries, according to the report.

An action plan being developed by the municipality includes everything from coming up with an emergency transportation strategy to a plan for rapid damage assessment. The district is also looking at the possibility of making a seismic expert available at minimal cost who could advise residents and business owners about their risks.

Walton said residents must also do their part to identify risks and come up with emergency plans for their own families. “It sounds like a simple thing but it can save lives,” he said.