On the morning of Friday, Oct. 2, 1942, while on a training mission, 27-year-old Royal Canadian Air Force Pilot Officer Arnold Ridgway flew his P-40 Kittyhawk fighter plane into a fog bank above Lynn Creek and never returned.

He was one of the very few Second World War casualties to die in service while on the North Shore.

Now, 75 years later, one of the first people to arrive at the scene of the crash is hoping to create a permanent memorial in Ridgway’s honour.

Archie Steacy was 13 when he heard his mother chatting with Lynn Valley School’s principal about a plane that had nearly struck the school that day.

“It was probably 100 feet in the air. Those planes had a Rolls-Royce engine, 12-cylinder, so they make quite a bit of racket – quite a roar,” Steacy said. “Shortly after, he said, the sound stopped.”

Later that night, the evening edition of The Province newspaper reported that a plane had gone missing in the North Shore mountains.

The next morning, Steacy and his older brother rode their bikes up to the top of Lynn Valley Road and into Lynn Canyon Park in hopes they might find something. When they looked to the north from the Rice Lake bridge, they could see a column of smoke coming up from the creek. They clambered down the creek’s banks and followed it to the scene of the crash, in a U-shaped gully.

“Two or three of the trees were sheared off so you could see the angle of descent. It went in there nose first,” he said. “It just blew up. It just went to pieces. When we were there, it was still burning. I can still smell it. It’s funny.”

There was no sign of Ridgway, though, Steacy said.

“There was nothing. Everything was burned and it was just small parts and pieces. He probably would have flown in there at about 350 miles an hour. Maybe more. That plane just went into a million pieces and he would have went into a million pieces with it. And anything there would have been incinerated.”

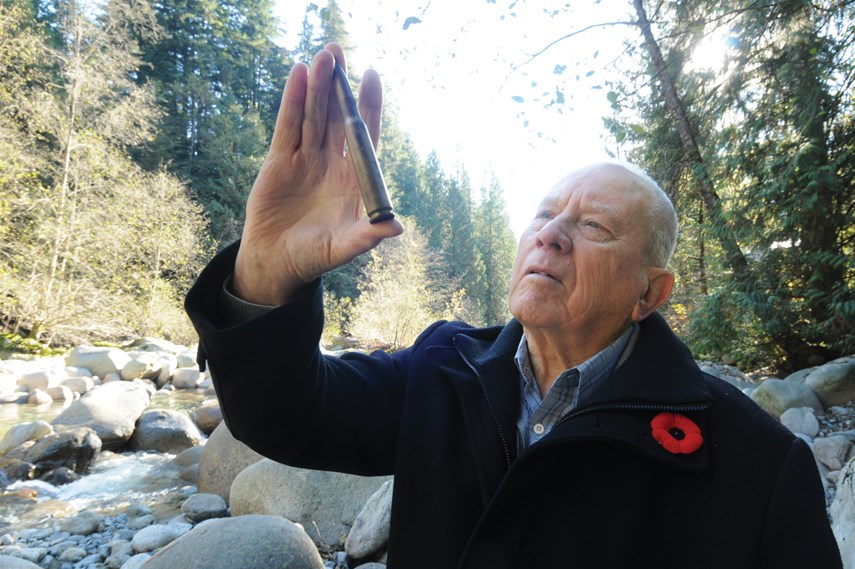

The Steacy brothers spent an hour walking around the smouldering wreckage. The plane’s .50-caliber machine gun was one of the few identifiable pieces left, although it had been twisted and bent. Steacy collected a few of the live bullets as souvenirs and one empty casing, indicating it had gone off at some point in the crash.

Enthused by their find, Steacy returned with some friends the following day. By that time, the scene was crawling with air force staff collecting what they could. A guard stopped them.

“He looked at us and said ‘What do you kids want?’ We said we came to see the crash site. He said, ‘Well I’m telling you to bugger off!’” Steacy said with a laugh. “He was this great big guy.”

Exactly what happened in the moments before the crash and why Ridgway flew into the fog remains a mystery. The official investigation found few witnesses. Among them were City of North Vancouver employees who were working at the water intake on Lynn Creek at the time.

“After it dived into the bush, I heard a loud bang and saw flames. I immediately telephoned the city hall for assistance and, on crossing the creek, saw the wreckage of the aircraft on fire. There was a light rain falling at the time of the accident,” George Atchison said in his statement to the air force investigators.

The testimony was corroborated by Frederick Burt and Henry Caspersen, also city employees, who added that the plane appeared to be in mechanical trouble.

“Immediately before the crash, I saw a flame coming from both sides of the back of the aircraft and a piece of the aircraft broke off in the air,” Casperson said in his statement.

But the crash investigators didn’t necessarily agree. Flight Lt. Thomas Broadbent Wood was the first RCAF member on the scene at 12:30 p.m., two hours after the crash.

“I ascertained as far as it was possible, that the aircraft was complete when it crashed,” he said, adding later, “No previous trouble had been experienced with Kittykawk AK 952 which would lead me to suspect that the crash would be due to mechanical failure.”

Fellow Pilot Officer J.R. Irwin had been following Ridgway in his own Kittyhawk on the training flight but opted not to stay in the fog.

“I continued for a very short time but on finding the visibility zero zero and knowing I was headed for the mountains, I made a 180 degree turn and came into the clear after about one minute. That is the last I saw of Kittyhawk AK 952,” his testimony stated.

The plane was in a steady left bank and diving at an angle of approximately 70 degrees immediately prior to the crash, the investigation found.

Ridgway was an experienced pilot with 681 flight hours, 102 of which were in a Kittykawk.

“Experienced pilot, deliberately flew into a fog bank at such a direction that he must have known would be dangerous if not disastrous, resulting in the aircraft crashing on the east side of Lynn Creek, North Vancouver, B.C.,” stated the conclusion of the Accident Investigations Branch.

The report described Ridgway’s injuries as “blown to pieces in explosion at impact.” His remains were sent to his parents, James and Mary of Outremont, Que. They buried their only son at Cimetière Mont-Royal.

Steacy, who was an army cadet and navy cadet during the war, enlisted in 1946 when he turned 18. He spent 38 years with the Royal Canadian Engineers, Royal Canadian Armoured Corps and the reserves.

Now as president of the B.C. Veterans Commemorative Association, Steacy is hoping to establish a cairn and small trail leading to the crash site. The association, which is made up entirely of veterans, has installed plaques and memorials all around B.C., and is responsible for the creation of the provincial program that distributes veterans licence plates for those who served Canada or its allies.

In the early 1990s, a Lynn Valley Legion branch 118 member who was a friend of Ridgway had a similar idea and approached Metro Vancouver, which has jurisdiction over the crash site. Mike Mayers, now a division manager with Metro, helped the man who was a senior at the time, down to the site and they drilled a plaque into a rock.

“I had never seen it, heard of it or knew about it,” Mayers said. “We just kept it sort of a secret because he didn’t really want the public to know there was something down there.”

Mayers returned to the site a few years later and found the creek had changed course numerous times, and much of the crash material had been scavenged or washed away.

Steacy has since been in touch with Metro, which has shown some interest in the proposal.

“We’re not opposed to things like that. It’s our history. Just get a plan together and let me know, and we’ll see what we can do,” Mayers said.

Much of the discussion at Remembrance Day centres around those who fought overseas, not so much so on the 35,000 Navy, Air Force and Army members who were deployed as a protectionary force in British Columbia, Steacy said.

The effort will be worth it, Steacy said, if it keeps Ridgway from slipping into the mists a second time.

“He was a serviceman and he served Canada. And unfortunately he was killed and so we want to remember him, just like all other people who have been killed overseas and through action,” he said. “This is crazy but I feel that he’s lonely. And if he’s not recognized and remembered, then his service was a waste of time.”