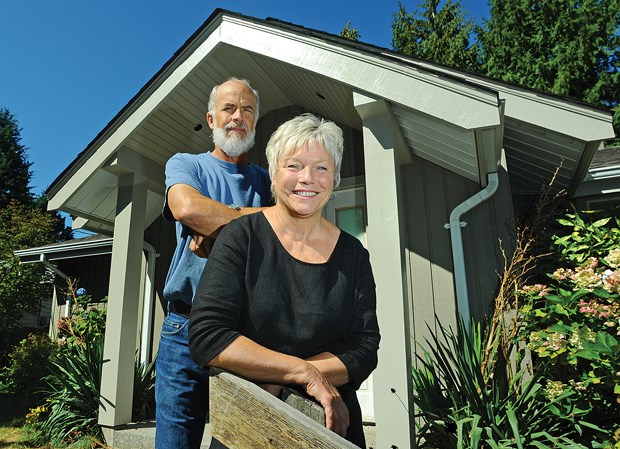

Malcolm McLaren was looking forward to settling down in his golden years with his wife Roberta. They had purchased the West Vancouver home he was born and raised in 12 years ago and it was finally time to enjoy it.

The McLarens have called the North Shore home for most of their lives. Their family home sat in a quaint neighbourhood where each home was a comparable size and respectable distance from its neighbour. The character of the street was a huge draw along with the sentimental attachment.

"When (Malcolm's) parents went to sell the home we asked to buy it through the family and everyone gave us their blessing," Roberta said. "So we did a bit of renovation all inside, but we kept the integrity of the house and moved in there. And the first couple of years we were there it was lovely because it was the neighbourhood that we knew."

But after a few years, a sudden shift in the neighbourhood began when construction crews started trickling in. Older, smaller homes suddenly started going down and in their place, "monster homes" started springing up, which the McLarens say did not fit in with the neighbourhood's established character.

"These homes are not built within a year," Roberta said. "They're built in two years - sometimes it takes that long to build them. So that started about 10 years ago."

One by one, For Sale signs went up and eventually the sold homes were destroyed. Malcolm said as one housing project would finish, another would start - the neighbourhood never really got a break for a decade.

"When you've got an established neighbourhood and then all of a sudden they dramatically change one house, it has quite an effect," Malcolm said.

The McLarens stopped recognizing their neighbourhood and no new friendships were formed with the new residents.

"The last straw was the house next to us that was built," Roberta said. "We just couldn't take it anymore."

The new home dwarfed their own, was very close to their property line and the barrage of construction noise finally pushed the McLarens out. They recently purchased a home in a Lynn Valley neighbourhood near their daughter.

"It wasn't a matter of downscaling, per se," Roberta noted. "Let's just go somewhere where it looks like nothing is going to happen to it for a few years so that we can settle and wake up and hear the birds sing."

On one hand, Malcolm said he appreciates the economic stimulus derived from developing larger homes - from the work the contractors get, down to the rented vehicles to transport materials.

"But there should be guidelines," Roberta added. "They need guidelines to protect the people who have established their home and life there.

"Through this construction you lose a sense of community."

A monster home is informally characterized as a large home, maximizing space on the property, and popping up in older neighbourhoods where houses haven't grown as much as the property value.

Each North Shore municipality has tackled the housing issue either with anticipatory zoning changes or reactionary ones.

Recently, the District of West Vancouver has been mulling further singlefamily home regulations to potentially curb monster homes.

At the last council meeting before summer break, some council members said it was time to consider limits on the maximum size of homes - even on large lots - to conform to the character of established neighbourhoods.

Coun. Nora Gambioli at the time said she was willing to set a square footage cap if it came to that.

"It's going to be a hot topic during election time," Gambioli told the North Shore News. "I suspect we're going to have a very big fight on our hands with builders."

Council's conversation hinged on a 16,000-squarefoot house that is currently being built in Caulfeild, which Gambioli likened to being the same size as a hotel.

But the discussion was also driven by a staff report that canvassed West Vancouver residents about monster homes and retaining public boulevards, which could shape future policy.

"There's a recognition the community as a whole is concerned about housing bulk and housing character," said Chris Bishop, District of West Vancouver's manager of development planning.

Bishop said while the district doesn't want to overstep its boundaries, it wants to address the concern raised by residents over large homes taking over their neighbourhoods.

There are specific regulations and standards that govern each zone in the district, Bishop said.

For instance, if a site is greater than 885 square metres (just over 9,500 square feet), a home's building footprint is capped at 30 per cent of that. But if the site is less than 664 square metres (about 7,200 square feet), a home's footprint can cover 40 per cent of that.

While only two-storey homes are allowed, crawl spaces, non-habitable attics and basements are all exempt from being counted as a storey.

Where the residence is, what type of slope it's on and what it's near all factor into measuring the building.

"People's homes are their castles," Bishop said. "But hopefully through our regulation and guidance from the district, we can help people recognize that what they build does have an impact on their neighbours and to try and really fit in and harmonize that as much as possible."

This September, West Vancouver council is expected to hear back from staff with a draft zoning bylaw including changes to floor area exemptions and retaining wall regulations.

But staff is also expected to report back on other alternatives to address monster homes in early 2015.

On the North Shore, the issue of monster homes finding their way into established neighbourhoods is not a new one.

In the mid-1990s, the District of North Vancouver started hearing rumblings from residents who complained that larger homes were taking away the character of the existing areas.

In response, the district started a process to update its zoning regulations to control the construction of new homes in established neighbourhoods, according to Stephanie Smiley, the district's communications co-ordinator.

Deemed The Neighbourhood Zoning Program, it developed over several years with the help of community input and resulted in 14 customized district neighbourhoods.

The zones guide new home construction, taking into account the existing patterns in each neighbourhood, while still allowing larger homes to be built, Smiley said.

The limits on house sizes range from 279 to 465 square metres (3,000 to 5,000 square feet) depending on the zone, which do not reflect the potential additional space in underground basements. Also, in most zones, upper floors must be smaller than main floors to avoid box-like houses.

Then in the early 2000s, the District of North Vancouver updated its zoning regulations including maximum floor space ratios, height restrictions and upper storey restrictions.

"Overall, the neighbourhood zones and the revisions to the zoning bylaw have allowed us to balance needed neighbourhood renewal as older homes require replacement," said Smiley in an email.

Unlike the North Shore's two districts, the City of North Vancouver hasn't had the same issues with monster homes.

"We don't seem to have had the same kind of proliferation of monster homes or same kind of proliferation of complaints (about) monster homes as you've seen in West Vancouver, Port Moody, and some other regional municipalities," said Emilie Adin, the city's deputy director of community development.

The city's zoning bylaw has been in place since about 1926 and has changed incrementally over time, Adin said.

The city requires that single-family homes can't exceed a 0.5 floor space ratio.

"I know some other municipalities rather than having a (floor space ratio), they control the size through setbacks or height and that sometimes leads to builders trying to maximize the building envelope," Adin said.

An average of 30 to 40 home demolitions and rebuilds occur per year in the City of North Vancouver.

However, its demographics differ from the two districts as single-family homes only comprise 15 per cent of the dwelling types in the city, according to 2011 data from the National Household Survey. Eighty-five per cent of the city is made up of multi-family dwellings, such as apartment buildings and townhomes.

The city also offers incentives and allows coach houses to discourage unnecessary demolition of homes built before the 1960s, Adin said.

"Houses have grown larger in every municipality in North America since the post-war period," she added. "So we certainly see larger homes and more square foot per capita, if you will, just gradually."

But one North Shore designer wants to see houses moving in the opposite direction, and says the time for monster homes has come to an end.

Kevin Vallely has worked as a designer for several architectural firms in Vancouver and abroad. He's designed an 80-storey tower in Manchester, England, three schools in B.C. and a civic centre for a B.C. First Nation community. Vallely now focuses on single-family residential homes.

"The cost of building a home is insane," he said. "There's sadly this trend, and this trend is certainly driven by the real estate industry, to maximize the buildable area on a lot."

Vallely said it's wrong to design a home on the anticipation of its resale value. "I think one can really live smaller and frankly live better because (otherwise) you're just left with area to clean and furnish," he added.

The North Shore doesn't have the same luxury as the Fraser Valley to sprawl out with no limits, which means densification is the future and big family homes will become a thing of the past, according to Vallely.

With rising energy costs, it will become more challenging to justify having a monster home where every bedroom has an ensuite bathroom and the cost of heating the home will rival the annual property tax cost.

"As time goes by, as more people want to live here, which invariably they do... well there's no place to move other than to densify," he said.

Vallely said he lives by his motto. His family of four lives in a home that's 1,400 square feet.

"I don't propose we all live in such a spartan way, but it's something to reflect on," he said. "What do we really need in the excesses of our cultural world?" Yet, another seasoned building designer based in West Vancouver takes a different approach on the issues of monster homes.

Marque Thompson started his career more than 20 years ago and is the principal designer of his company Design Marque Consulting, which specializes primarily in residential building.

He said builders aren't involved enough at the municipal level, and it's their livelihoods on the line when planning departments cross the line by reacting and shaping policy to subdue a "vocal minority."

"It's affecting the construction industry," Thompson said about the trend to greater regulation. "It's affecting how we design a house and it's largely affecting the value of people's properties."

He notes that what exactly a monster house is needs to be defined.

"Is it the way it's designed? Is it the way it sits on the lot? Or is it really badly built and badly designed?" he asked.

Thompson said when people were building an average of 2,100-square-foot homes 60 years ago in West Vancouver it was due to expense, land costs and the limitations of construction machinery of the time.

"These lots now in here are costing around $2 million," he said. "So to ask someone to build a 2,100-square-foot house on a $2 million lot is not sensible or practical."

Instead, the municipalities should encourage people to build a house and use every square inch inside it - from the attic to the basement.

"We should be encouraging that before we tell you to build a laneway house," he said. Thompson said more regulation could create a whole new set of problems.

"When you turn around in 2014 and say you can't build the same house that someone built in 2013, it's going to cause a shockwave," he added. "It's going to cause problems."