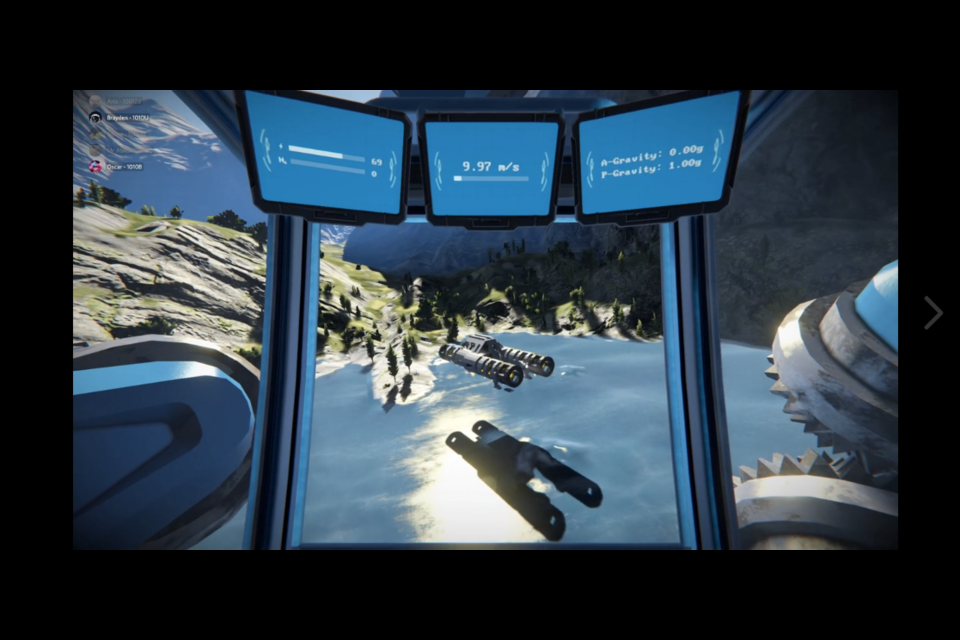

Inside a giant ship that’s just taken off from the planet’s surface, the pilot looks down on a mountain valley below. It’s dotted with small trees, and glacier-covered peaks loom in the distance.

As the ship flies down the valley, another flying craft comes into view, thrusters firing. The two ships head back to a small glacial lake, where the second space ship descends, slowly, on to its frozen surface.

The video, which includes being in the middle of a realistic world, might feel familiar to teenaged gamers.

This virtual world is one with a difference though – both the environment and all of the components, including the spaceships, have been created on a special online platform by students of the West Vancouver school district’s robotics academy.

Unlike a typical video game, the Space Engineers platform allows students to set their own objectives, and then figure out ways to work towards that.

“It’s a very technical game,” said Todd Ablett, the robotics teacher who has turned to the online platform to keep students engaged in problem solving in the virtual world.

“There are a lot of variables you have to manage.”

Space Engineers "Operation Big Boi" from Oscar Price on Vimeo.

The operation on the frozen lake, for instance, was part of an ice-mining operation so that ships would have water to fuel their hydrogen engines.

Physical distancing rules dictated by COVID-19 created a particular challenge for robotics students, said Ablett, because the work is usually so hands-on. “You sit in a room with a whole bunch of people, you build things, you work with tools. So that's right out of the question right now. We’d have to be in hazmat suits or something like we're prepping for a NASA mission.”

Fortunately Ablett already had experience with the Space Engineers platform, and thought it would be a good way for students to keep their minds focused on some robotics challenges.

Just like in the physical robotics class, there’s lots of teamwork, trial-and-error and sharing of information on the virtual platform, said Ablett.

The space ships put together in the game by students have to fly using the physics of the world they have created. “If you don’t put a forward thruster on it when you go to stop, it drives into a wall,” said Ablett.

Unlike many video games, there’s no cheating by returning to the last point you saved. If you crash, “your vehicle is now laying in pieces on the ground” and becomes a new problem to solve.

The engineering game is set about 50 years in the future “with the real technologies they think we’ll have developed by then,” said Ablett. “It’s not Star Wars.”

So there’s a possibility students in a class like this could be part of engineering solutions for renewed lunar or Mars exploration in the future, said Ablett – not such a farfetched prospect.

About 12 to 15 kids are routinely checking in to the platform, said Ablett. Some use it as a place to let their minds get creative between more heavy-duty online courses.

It’s a place where students can chat with others as they work in small groups. In a strange way, said Ablett, the virtual world the class is creating is also a place where students can “go” while so much of their real world is off limits to them.

Ablett said he misses his robotics class. “It’s neat to watch the kids building things,” he said. “This is pulling some of that back together.”

As a sign of success, some have already asked him, “When (the pandemic) is all over, can we still run this?”