This story has been updated to add new information from the province.

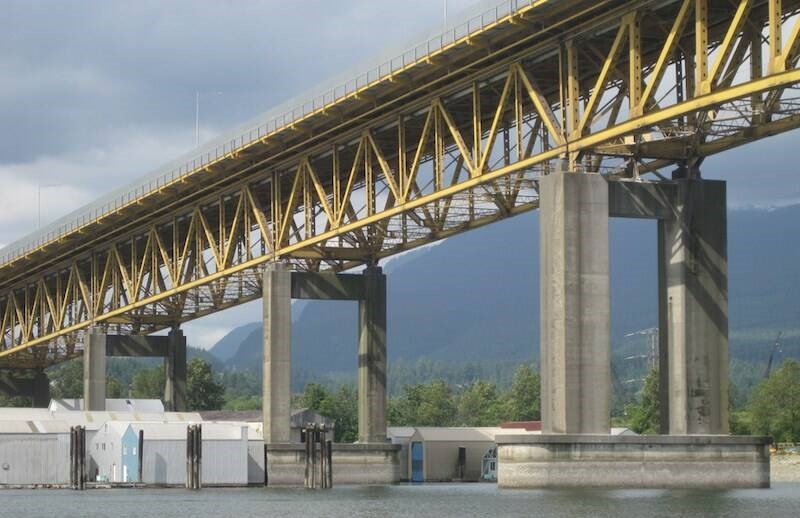

The province is looking to shore up protection of the Lions Gate Bridge and Ironworkers Memorial Bridge in the event of a major ship strike.

And the province's Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure is starting to make longer-term plans for the future of the Ironworkers.

The ministry is seeking engineering firms to design in-water structures that would halt or deflect a vessel drifting off course before it collides with the bridge foundations. A strike on one of the bridges has the potential to partially sever the North Shore from Metro Vancouver.

The impetus for the project is a change in federal engineering standards. In 2015 the province commissioned a study that found the annual risk of collapse from a vessel strike on either of the bridges was less than one in 1,000. That level of risk is considered acceptable for lesser bridges, but the newer federal standards state the risk should be less than one in 10,000 for “critical” bridges, like the Lions Gate and Ironworkers.

The Lions Gate Bridge and Ironworkers see approximately 60,000 and 125,000 crossings per day, respectively.

In 2018, the ministry sought engineering firms to begin preliminary design work and option analysis but never proceeded with detailed designs and contstruction.

North Vancouver-Lonsdale NDP MLA Bowinn Ma acknowledged that the update is a positive one.

“While the damage of a vessel impact is very unlikely, these crossings are so critically important to the North Shore, to the province, and really nationally, these protections are overdue,” she said. “The retrofits are meant to complement the stringent vessel transit procedures put in place by the by the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority for the safe movement of people and goods through the Burrard Inlet.”

Ma said the North Shore has already seen what happens when a pothole requires just one lane of the Ironworkers to be closed, or when a snowstorm prevents health-care workers from commuting to Lions Gate Hospital.

“The consequences to the North Shore would be just extraordinary,” she said. “It could be absolutely catastrophic for us.”

The ministry will be consulting with regulatory bodies, Indigenous groups, local governments, the marine industry and boaters for the exact designs, but they do know the protection for Lions Gate Bridge will require a rock-fill berm at the base of its south tower, similar to one already in place at the north tower.

Structurally, the Ironworkers still has about 40 years of life left in it, but later this year the province will begin a study into where it fits in the longer term. Exactly what that study will include hasn’t been decided yet, but Ma said at least one part of it should be clear.

“I would say it’s quite critical that the terms of reference for this work include consideration for how it dovetails with the concept of a rapid transit solution for the North Shore. That’s a concept that the North Shore has done substantial work to get off the ground,” she said.

As for those eager to see the province get to work on a wider replacement today, Ma cautioned that more lanes of travel won’t have the desired effect of congestion-free commutes.

“Even if we cross more cars over the bridges onto the North Shore, where do they go on the other end? A lot of them spill into our local streets and jam up our local streets,” she said.

Far more effective will be concentrating new development in areas with access to transit, shopping and services so residents won’t be so reliant on cars and roads for all of their needs, she added.