In a downstairs classroom at West Vancouver Secondary, Grade 12 student Caroline Wallace stands over part of a ’bot, tightening the tension on a chain.

It’s a detail that’s important in getting the robot to do what it’s supposed to.

A chain with the right tension means the encoder built into the ’bot will take an accurate measurement of the wheel rotation – and know how far the robot has moved, said Wallace.

Pliers, wires, plastic gears and sets of special “omni wheels” – which can also move sideways – lie on the desk in front of her.

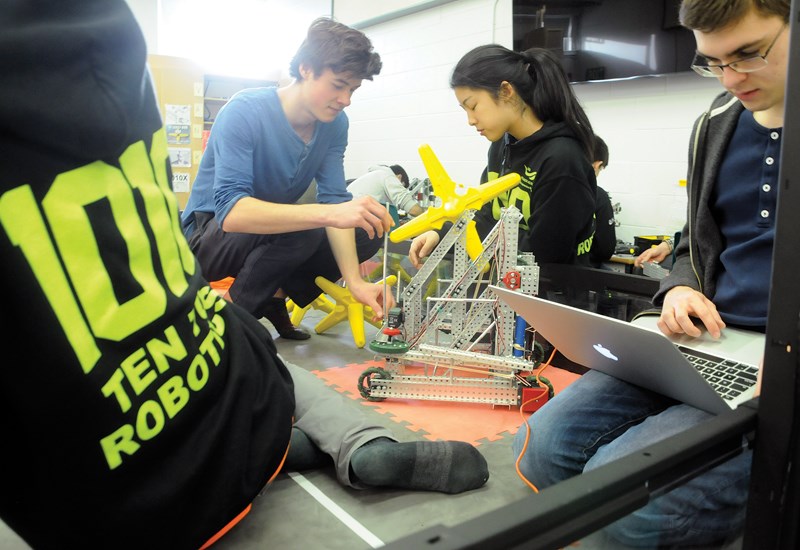

Around Wallace, the room is buzzing with activity. Groups of three and four students huddle over their robots, puzzling through their next steps, or type into laptop computers. Some perch on the edge of the 12-foot-square robotics “field” – which resembles a large table tennis surface – in the middle of the classroom.

This is where the robots must perform specific tasks during robotics competitions and score points against opposing teams by tossing plastic yellow “stars,” resembling oversized plastic jacks.

The process of thinking through how to achieve that, then coming up with solutions through trial and error, is at the core of what students at West Vancouver’s new mechatronic robotics academy are learning.

“There are often many solutions, not one, but there are better solutions,” said teacher Todd Ablett, who runs the robotics academy.

“If you do it more, you get better solutions.”

The new academy, which started in September, is one of the ways West Vancouver students are learning about coding – a skill being emphasized as a key to future opportunities.

In the first year, there are about 50 students – who range from grades 9 through 12 – in the academy. Of those, 10 are girls.

"I got one of the last spots in the academy,” said Wallace. “I thought academies were for sports. I was never a sports kid.”

“It’s super different to what I’ve seen in school,” she said. As a student focused on math and sciences, Wallace spends a lot of time with books. “I don’t get to work with my hands a lot.” Here, she does. “I like to apply the physics and math I’ve learned to build something.”

Ablett says it’s important for all students to be exposed to the basics of coding, because areas where these skills are incubated first stand to become leaders in the technology industries of the future. “Think Silicon Valley in the (United) States,” he said. “We don’t want to be lagging.”

He laughs as he remembers telling students a few years ago that “one day” their children would see self-driving cars – now already a reality.

At its most basic, coding is “how you usually tell a machine to do something,” said Ablett. “We have all kinds of smart and semi-smart machines now in our world,” he said.

More people will code in the future because “there’s more things to code,” he said. Everything from bicycle lights to refrigerators to 3-D printers use coding.

Even among students who won’t go on to careers in engineering, “it’s good for teaching critical thinking,” he says.

Students in the academy learn how to take their mathematical theories and apply them to the real world which can involve random curve balls like surfaces which aren’t quite smooth or objects that have slightly different weights.

Learning to work in a team is key, and students with more knowledge and experience are expected to teach others. “There’s a fair bit of apprenticeship that goes on here,” said Ablett. “Teaching someone is the fastest way to learn it.”

Perched on the edge of the VEX robotics field, Grade 12 student Kyle Alexander is working through a problem on a laptop computer. “I’ve always been interested in coding,” he says.

Alexander says he likes to figure out how things work. “There’s a fair bit to learn,” he says. “Actually getting it to work on a robot is a little different than getting something to appear on a screen.

“It’s a lot of time and error,” he said.

Some students in the robotics academy have worked on their own special side projects, including building and flying drones – often built from modified kits, but sometimes constructed from the ground up. Drones are essentially “a flying robot,” said Ablett, who expects their use to expand exponentially in the not-too-distant future.

One student even added electric motors to his skateboard, so it can go up hills. “It has two motors underneath it, lithium batteries and a remote control. His top speed so far is 40 kilometres an hour.”

“This is the inventor stuff we want kids doing,” said Ablett. Today the project may be a skateboard but “who knows where that leads?” he said.

One other key quality that robotics teaches is resilience. “It’s the most important thing a person can have,” said Ablett.

“If you are going to build robots, you are going to fail at times. It’s how you react to that failure that makes all the difference in the world.”

In a modern world where things are easy, students need problems that are tough to solve “so they can develop some resilience,” said Ablett.

“The only people who never face failure never try anything.”