When he was 12 years old, Robert Otto woke up on a New Year’s Day and knew something wasn’t right. It was cold in the house, colder than it should have been, even for an Ontario winter. He crept downstairs and saw the sliding glass window to the family room had been smashed. In the living room, things were missing.

His parents called the police and soon the forensics team showed up. Otto followed them around as they dusted for fingerprints and took photographs of shoe impressions in the snow. He found their methodical presence calming.

He also knew their work was what he wanted to do when he was old enough.

Today, Cpl. Otto is a member of the six-member forensics unit (including one apprentice) working out of the North Vancouver RCMP detachment, one of five specialized units that work out of larger police detachments in Metro Vancouver. Their unit covers a wide area, including both the North Shore, Sea-to-Sky corridor, Bowen Island and Sunshine Coast.

As forensic specialists, their job is to collect and analyze physical evidence from crime scenes, using science to assist in investigations that can range from homicides to stolen bikes.

On the North Shore, forensics have matched DNA on a bottle of Sprite to an arsonist who set a fire in a university library. They have also matched fingerprints found in blood on a doorframe to a man present at a violent beating at a drug house.

Crucial team works behind the scenes

It’s about a two-year undertaking for a police officer to become a forensic specialist, a process that involves training with the Canadian Police College and apprenticing within the unit. There are also a series of increasingly difficult identification tests and a dissertation-like defence of an identification case that officers must successfully complete before becoming certified as a forensic specialist.

Work of the forensics team can be crucially important to police work, but apart from the appearance in hazmat suits at major crime scenes, most of it takes place out of public view.

Collection or analysis of bloodstains, footprints, fingerprints, ballistics, hair and fibres, video analysis and crime scene overviews are all done by the forensics unit.

Depending on the crime scene, forensics specialists can be looking for everything from discarded cigarette butts and pop cans to shell casings, bullet holes, and fingerprints left at a crime scene.

A basic crime scene kit includes a variety of fingerprint powders, as well as camera gear. These days, officer frequently bring a portable laser for drafting quick, accurate crime scene diagrams – a process that used to be done on paper and took many times as long.

Other specialized equipment will be brought along depending on the job.

Among those is a metal detector, which can be set to find different types of metal at different depths.

“It can help you locate evidence that isn’t obvious or visible,” said Otto – a bullet that’s been shot into the ground or may be covered up by leaves, for instance.

In cases where guns have been fired, officers look for everything from the rifling present on the weapon and/or bullet, the presence of lead around a hole indicating a bullet has been shot into it and residue from gunshots that may be left on a suspect’s hands.

Bullet trajectory rods also help give officers a more accurate idea of where a bullet may have landed – upping the odds of recovering it.

Chemical recipes help reveal hidden fingerprints

Collection of invisible evidence that lies just under the surface – DNA in spots of blood, or fingerprints left on a countertop – is among the core work of the forensics team.

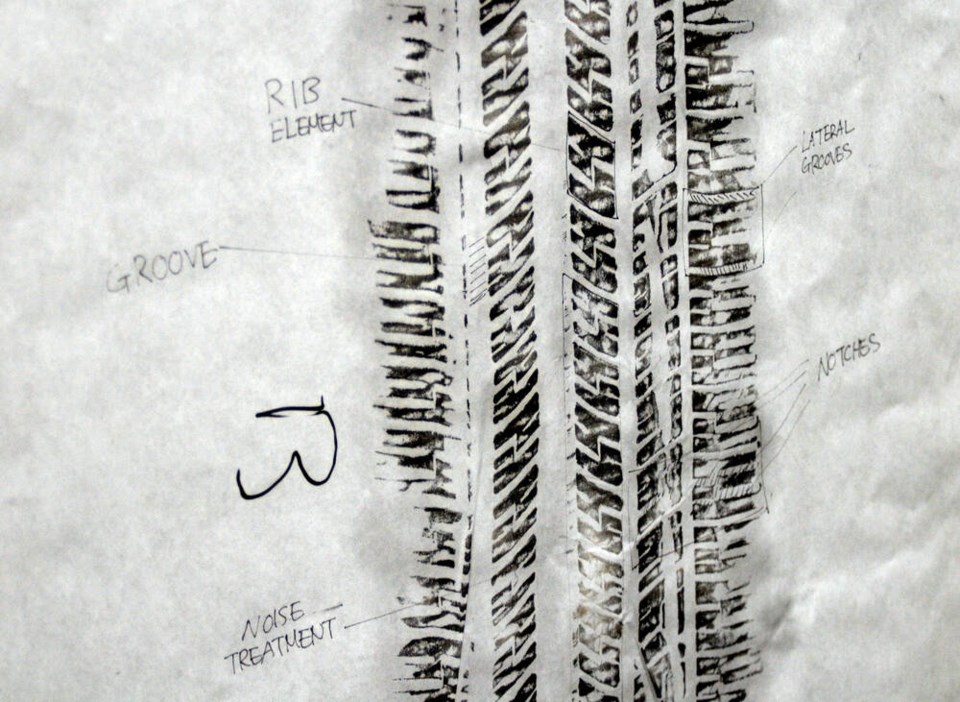

Human fingertips contain unique pattern of skin ridges, whorls and other characteristics formed during fetal development that remain stable through a lifetime. When someone touches a surface, the natural oils in the hand leave a trace of these unique patterns.

Dusting surfaces with various coloured and textured powders to provide contrast remains the easiest and most efficient way to find fingerprints.

The standard fingerprint powder is a chemist’s grey, and the best place to find fingerprints is a smooth, non-porous surface. Those kinds of prints are relatively easy to “lift” with large pieces of adhesive squares called “hinge lifters.” Those prints can then be photographed and the contrast enhanced further using digital techniques.

After about 10 days, however, oils that left a fingerprint tend to dissipate, and different methods are needed.

Those involve using different types of highly sensitive powders that react to lights, including everything from UV, blacklight or specialized lasers or filtered glass to make latent fingerprints visible.

The forensics section in North Vancouver includes both a “dry lab” and a “wet lab” where various chemical “recipes” can be mixed to bring out latent fingerprints.

One of the methods for identifying fingerprints involves using a chemical known as ethyl cyanoacrylate, essentially a form of Krazy Glue, and heating it in an enclosed humidity chamber. As the glue cools, it adheres to the oils that the fingerprints have left behind, providing a print.

For fingerprints on other surfaces, like receipt paper, for instance, forensics officers might use another chemical, ninhydrin, which will react with the oils in a fingerprint and turn purple over several days.

While some more sophisticated criminals wear gloves to avoid detection, just as many don’t, said Otto, especially in opportunistic crimes.

Portable lasers and ultraviolet lights can also reveal evidence like bodily fluids, blood or prints that aren’t readily visible with the naked eye.

“In certain cases, if a wall has been freshly painted, you may be able to see evidence of hand marks under the paint, which could tell its own story,” said Otto. “Maybe there’s a struggle that’s been covered up.”

Forensics officers also use special chemical reagents for detecting blood at crime scenes that may not be visible. Those chemicals react with the iron component in blood cells and can show blood that’s seeped down into floorboards, for instance.

Clues can be found even after crime scene 'clean up'

In more serious gang-related crimes, the most common method of “cleaning up” a crime scene is for those responsible to burn the evidence – usually by setting fire to a vehicle.

But even in those cases, sometimes clues can be extracted, said Otto.

“You think there’s nothing left, there may not even be a steering wheel,” he said. “As things burn they tend to compact down. You may take out a chunk of the floor, X-ray it and there’ll be firearms in there. You chisel them out and they’re very well preserved. Or you might get footwear that’s been pancaked down and melted.… Sometimes strange things happen.”

Once evidence has been identified, careful handling procedures are followed to keep evidence secure with exhibits tagged and entered into a computer system and checked in and out of evidence lockers with one-way keys.

Video analysis has taken off

Among the biggest changes in forensic science in recent years has been both the use of drones to capture crime scenes far more accurately than was possible in the past and the rise of video analysis.

On the local scene, video analysis really took off after the Stanley Cup riots of 2011, said Jon Stringer, a civilian video analyst on the North Vancouver’s RCMP’s forensics unit. Video experts from all over North America came to Vancouver in the aftermath and reviewed the video evidence that led to later convictions (including people from the North Shore who were involved in the riots.)

Now, with the rise of more sophisticated home security video as well as commercial cameras, “the prominence of video evidence is increasing exponentially,” said Stringer. “If you’re in downtown Vancouver, you’re on camera every few seconds. So one of the first things you probably look for in a file, when you’re trying to identify someone, is if there’s video.”

For the forensics unit, there’s a more dispassionate science involved than in some other aspects of police work. Often when they’re collecting DNA evidence to send to a specialized lab or collecting fingerprints, they don’t know exactly how that evidence will be used to further a case, said Otto.

“It’s just the facts,” he said. “I’m not tied to it in the same way emotionally as a [police officer] may be who’s closer to the interviews and things like that.”

Unlike scenarios depicted on crime shows like CSI, forensics experts usually aren’t involved in the larger parts of the investigation, like talking to witnesses. Results from tests like DNA swabs also take considerably longer to get back from the lab in Ottawa – sometimes running to several months rather than being wrapped up within the hour.

“In reality, there are homicide trials [that Otto worked on] a couple of years back that are just going to trial now,” he said.

But the reverse is also true – forensic evidence, if it’s properly handled, tends to stick around.

When fingerprints are located at a crime scene, they’re put into a database to search for potential matches. But if there’s no immediate match, that database will continue to run the search every day. “You could get a reverse hit, it could be five years later, whenever that person responsible is arrested and fingerprinted for another offence,” said Otto.

That brings some satisfaction, he added. “It’s kind of like time travel,” he said.

“These individuals could have gotten away with whatever they had done … but when you find the forensic evidence, you can kind of bring them back, and hold them accountable.”