Thousands of Canadians gathered on a stretch of beach on the coast of Normandy in France today to commemorate the 75th anniversary of D-Day, one of the most pivotal days of the Second World War.

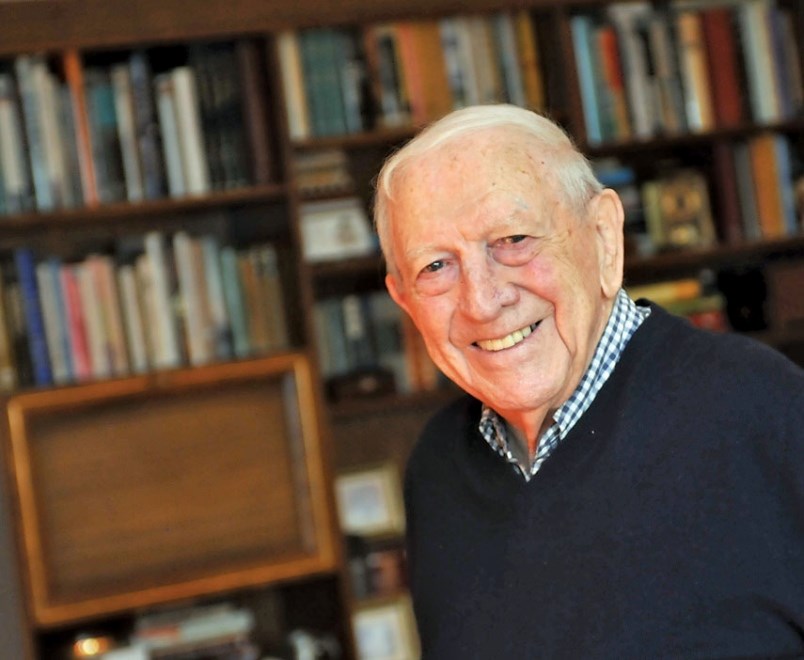

Amongst those gathered were West Vancouver’s Harry Greenwood and Lions Bay resident Norman Kirby, two North Shore veterans who fought with the Allies.

As a member of the Royal Navy, Greenwood was a signalman aboard Deep Sea Rescue Tugs, and saw action wherever his vessel was called to serve, including at Normandy on D-Day. Click here to read a profile of Greenwood, who came home from the war to become a community leader, earning the title of Citizen of the Year from the West Vancouver Chamber of Commerce in 2016.

Kirby was 18 years old when he landed in Nazi-occupied France, immediately thrust into the chaotic nightmare that was the Invasion of Normandy. You can read a 2014 profile of Kirby here.

It was on June 6, 1944, that 14,000 Canadian soldiers — men from across the country and all walks of life — stormed ashore under withering German fire to begin the long-awaited liberation of Europe from the Nazis.

In the pre-dawn hours before the invasion and after crossing the English Channel under cover of night, the Canadians, as well as their British and American counterparts, loaded into landing craft to prepare for the assault.

"We got in those boats and the coast was terrible," recalled Joseph Edwardson, who was 20 on D-Day and a member of the Royal Regina Rifles, one of the first Canadian units to step foot in Nazi-occupied France.

"It was a bad, bad morning. And the water was splashing into the craft and they were starting to take water, so we had to use our helmets to bail some of the water out."

And then the attack was on. Richard Rohmer, a young Canadian pilot had a birds-eye view of the invasion while flying over the beaches as the landing craft, supported by the heavy guns of Allied warships, approached the coast.

"The site was fantastic: Guns firing from the naval destroyers and ships, landing right over where we were flying at 500 feet," said Rohmer, who later rose to the rank of major-general in the Canadian Forces.

"It was fantastic to see the incoming ships, the incoming landing craft and the explosions of the battleships that were firing right where we were flying. … It was quite a day."

But the Allies weren't the only ones shooting. The Germans had long prepared for an attack and now opened up with machine-gun and artillery, while some of the Canadian landing craft hit underwater mines.

Jim Parks was on one such landing craft and was forced to dive off into four metres of water and swim for shore. Once there, he helped pulled wounded friends to safety, some of whom would die on the beach.

"One guy was Cpl. Martin, he was from somewhere in Manitoba," remembered Parks, who like the others is now in his mid-90s. "He'd been shot in the chest and his lungs, so he just died right there in our arms."

Before D-Day was over, 359 Canadians had died, more than double the number that died during the entire war in Afghanistan. Another 715 had been wounded or captured.

But the carefully planned invasion was a success and would mark a turning point in the Second World War. The Canadians and their Allies had broken through Hitler's Atlantic Wall and established a foothold to start liberating the rest of Europe.

Two ceremonies are scheduled to be held on the eight-kilometre stretch of coastline now known as Juno Beach, where the Canadians came ashore and were able to push several kilometres inland on D-Day.

Like the attack on the beach itself, the first ceremony will be all Canadian with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau scheduled to speak along with some of the surviving veterans who fought on the spot 75 years earlier.

The second will be more international in flavour and include British and American delegations whose soldiers fought alongside the Canadians on D-Day, as well as representatives from France, Germany and other countries.

Al Boon, who like Edwardson, Rohmer and Parks has returned to Normandy for Thursday's commemorations, the event will bring back some hard and sad memories.

"My hardest time is whenever we are going through the ceremonies," he says, "and that is always the sad part about it."

- with files from Andy Prest, North Shore News