When Kevin Bell was just three or four years old, he wandered into an old garage on a particularly cold winter day in Northern Ireland and found a tiny blue tit on the verge of freezing to death.

“I picked it up in my hands and took it to my mother. And she revived it with some of that Second World War margarine,” said Bell. “And from that time on, I had an interest in birds.”

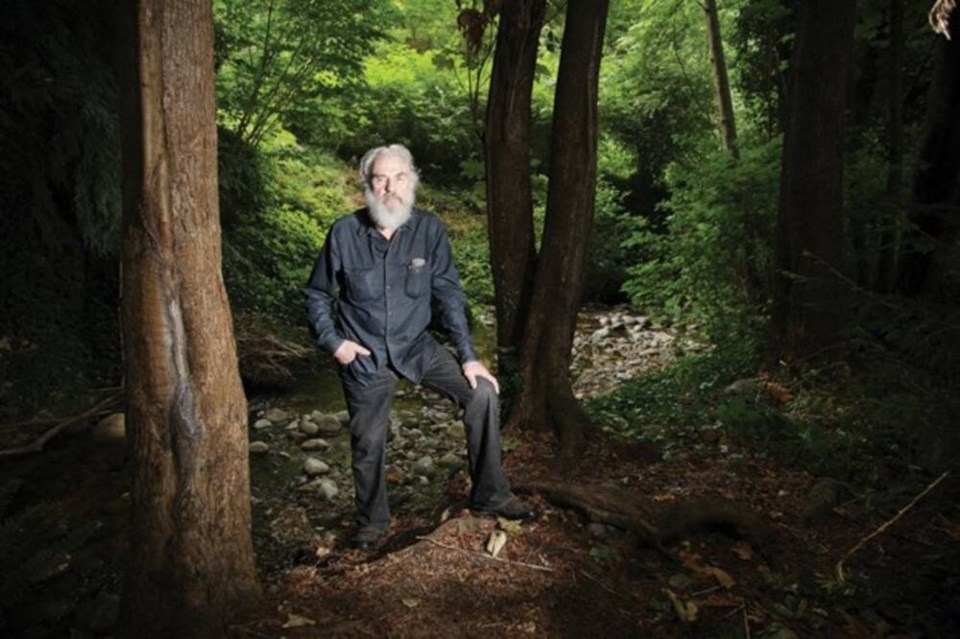

That interest in birds – and in the natural world – would go on to be a lifelong passion for Bell, leading to work as a nature educator at North Vancouver’s Lynn Canyon Ecology Centre, and an encyclopedic knowledge of birds and the natural world which he shared on North Shore bird counts and walking tours for more than 40 years. It was also behind Bell’s impassioned fights on behalf of the environment, including a successful campaign to save Maplewood Flats as migratory bird habitat.

Maplewood marks 30 years

This year marks 30 years since the former industrial wasteland, including 96 hectares of mudflats and salt marsh plus 30 hectares of upland forest grassland on the North Vancouver waterfront, was set aside as a conservation area, turning around a plan at the time to convert the area into a shopping centre. Bell was instrumental in a campaign by the Vancouver Natural History Society to save the area as migratory bird habitat.

It was far from pristine wilderness, but it was a critical piece of habitat not found elsewhere on the North Shore. Efforts by volunteers there, including Bell, eventually led to the return of purple martins – once headed for extinction as their habitat was wiped out – and ospreys to the mudflats in the 1990s for the first time in 50 years.

“I’ve always tried to think globally and act locally. You’re trying to do both, but locally, it’s so much more doable,” said Bell.

Bell honoured with conservation award

Earlier this month, Bell was chosen as this year’s winner of the Alan Duncan Bird Conservation Award, co-ordinated by the Stanley Park Ecology Society, for lifetime contributions to championing bird habitat conservation across the Lower Mainland, through organizations including Nature Vancouver, the Western Canada Wilderness Committee, the BC Field Ornithologists and the Wild Bird Trust of BC.

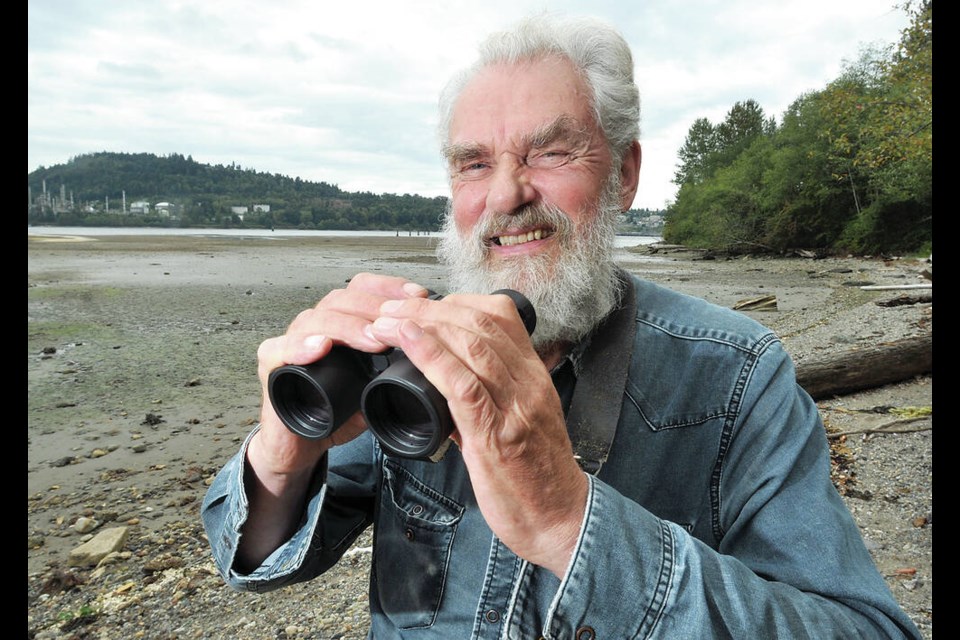

Rob Lyske, another North Vancouver birder, said he likely first met Bell when he went to the Ecology Centre as a child. Later, Bell and Lyske connected as fellow birders at Maplewood, where they would often sit on the beach together watching shore birds.

“It’s one of the few places on the North Shore that you can actually go and enjoy wildlife,” said Lyske.

Outspoken on environment

Over the years, Bell spoke out about many environmental issues, including a canola oil spill from a freighter in Burrard Inlet that wiped out a population of resident grebes for many years, and municipal use of the herbicide glyphosate (known by the trade name Round-Up) to control Japanese knotweed.

In 2006, Bell was among a group of protesters arrested for blocking crews building the new highway through West Vancouver’s Eagleridge Bluffs, over destruction of bird nesting habitat.

Bell acknowledged that some environmental fights were won, while others were lost, but he remained convinced about the need to speak out.

“We can give up and just let the world go to hell in a handbasket. Or we can fight. And I think it’s worth the fight,” he said.

Citizen science plays role

Bell took part in countless bird counts over the years, ranging from the annual Christmas bird counts on the North Shore, to annual breeding bird surveys near Pemberton.

Such amateur citizen science is important, Bell said, because it shows both corporations and governments that regular citizens are watching out for the natural world and taking note of what they see. That makes it harder to ignore environmental issues, he said, “and gave backbone to the government organizations which were supposed to do that job.”

Lyske recalled being on a bird survey with Bell in Delta and coming across an injured heron. The group decided to drive the bird to the Wildlife Rescue centre in Burnaby – a reasonable distance for a large wild bird in a vehicle.

“I have this lasting memory of this heron just sitting in Kevin’s lap,” he said.

Bell said though the planet has continued to skid downhill since he first began sounding the environmental alarm, the key is still for people to care and to act.

“People turn to technology. That’s like calling on God to intervene,” he said. “I don’t see Jesus Christ out there with a shovel fixing things.”

Bell learned that he’d won the award while at home this month in the final stages of fighting cancer. He died May 17.

He spoke to the North Shore News on the day he turned 81, while watching the forest birds from his deck in North Vancouver.

“I’m watching two towhees and the song sparrows and the black-capped chickadees. Every now and then a red-breasted sap sucker or a downy woodpecker will turn up,” he said. “It’s just marvellous.”