A rusted sawblade. A bit of tin. Neither are remarkable things to find in the second-growth forests around the Seymour River Valley.

But beneath the ferns and layers of sediment is another much more complex story: Japanese, or Nikkei, settlers who made a home in the wilderness and then, suddenly, vanished.

For some time, Capilano University archeology professor Bob Muckle had excavated and documented Euro-Canadian logging camps from the 1920s and 30s, but in 2004 a retired forester contacted him about a potentially interesting new site in the bush, about halfway between Rice Lake and the Seymour Dam. All that was on the surface were a couple of cans and a sawblade.

“I had no idea, until I started excavating and started coming up with rice bowls and sake bottles,” he said.

For the last 14 years, Muckle and his archeology students from Capilano University have been spending six weeks every spring digging through the soil to uncover the story of the people who lived there. More than a logging camp, Muckle asserts, it was an outpost where Japanese settlers could live free from the rampant racism in the city and hold onto their culture.

“There was very likely a small community of Japanese who were living here on the margins of an urban area,” he said. “I think they were living here kind of in secret.”

Muckle has been able to handpick the students that can join his small class and warns them all not to expect a walk in the park (though it does involve a trek many kilometres through the Lower Seymour Conservation Reserve each day.)

“I tell them you’ve got to be fit or willing to get fit – fitter than me because they let me take my truck in. You’ve got to get used to working in the rain because when it rains, we still work. And you’ve got to be comfortable working around bears, because bears are around,” he said, noting there had been one particularly aggressive bear that once raided their lunch sacks this spring. “It turns some people right off.”

They don’t bother recording every little scrap they find in the dirt, but for student Shaunti Bains, it’s still a thrill.

“I found a little plastic bit and a bunch of nails – a piece of ceramic over there,” she said. “I like it a lot. … It got really exciting to find things, even though it sounds silly. It’s a nail. I got way too excited at that.”

A NIKKEI VILLAGE

What they unearthed was not just a forgotten settlement but an entirely separate way of life, distinctly Japanese.

The area where the Nikkei village stood would have been clear cut by the Hastings Co. early in the 1900s, but the province granted logging rights for the neighbouring cutblock to Japanese businessman Eikichi Kagetsu in about 1918.

When the last of the trees had been harvested by about 1924, Kagetsu moved on to Vancouver Island to grow his business.

The football field-sized camp contained more than a dozen cabins along a cedar plank road, enough space for 40 to 50 people. Water was fed to the homes via a gravity-powered reservoir up the hill.

At the northernmost tip of the site, Muckle and his students unearthed a cedar platform and bits of green glass held together with wire – likely part of a lantern. Japanese visitors to the site mostly believe it would have been a shrine.

“When these loggers came back at the end of the day, this is the first thing they would see,” he said. “I don’t think anybody has ever found anything like that in North America, at any other sites.”

The flattest area of the site, oddly, contained no evidence of buildings but soil samples showed dense accumulations of burned bone and a higher pH level, indicating fertilizer for the community’s garden.

Perhaps Muckle’s favourite find is the bathhouse. During the first field season, a senior Japanese woman visited the dig and asked Muckle where the “ofuro” was. He’d never heard the term before, but she explained to him the cultural importance of bathing to Japanese people, and that “it would be ridiculous to think there would be no bathhouse here.”

After the worst night’s sleep in his life, Muckle came back early the next morning, determined to find it.

“I just started poking around. I could see I had a U-shaped structure here,” he said, standing over the remnants, beaming. “We actually found part of the tub. We found the bucket and ladle.”

When Naomi Yamamoto took Muckle up on his offer for a tour, seeing the bathhouse gave the former MLA chills.

“Baths are really important in the Japanese culture. I never took a shower until I was quite a bit older,” she said. “And I’m a fourth-generation Canadian.”

Although her surname Yamamoto means “One who lives in the mountains,” Yamamoto said her ancestors came to B.C. to fish. Still, she found the visit to the site deeply stirring.

“It was magical. It was so extraordinary and, I don’t know – otherworldly,” she said. “All I could think about was these last 10 decades and how many trees have fallen and rotted, and all the pine needles that have covered up all these things that Bob and his students have uncovered recently.”

Both of Yamamoto’s parents were sent to internment camps. Her grandparents’ homes and fishing boats were confiscated and never returned.

Yamamoto was in government in the spring of 2017 when the province officially commemorated the site for its significance to British Columbians of Japanese descent, thanks to Muckle’s work.

Daien Ide, reference historian for the North Vancouver Museum and Archives, visited the camp in 2019. By coincidence, Ide’s grandfather was a mill worker who was later employed by Kagetsu on Vancouver Island.

“I connect to it in a different way,” she said.

Ide said she couldn’t help but contemplate how it would have looked and the lives of the people who lived there, especially when she saw the pottery and trinkets they left behind.

“You think about how far they would have walked or how difficult it would be to get those heavy logs in and out of that area,” she said.

INTERNMENT

That a community of Japanese loggers and their families lived there isn’t really up for debate. Far more interesting is the question of how long they stayed. Muckle’s theory is that even after the logging was done, some of the Nikkei inhabitants chose to stay – possibly right up until 1942 when the Canadian government began detaining people of Japanese descent and moving them to camps in the Interior.

There are no records of who lived in the camp or where they went, but the preponderance of items found intact suggests the inhabitants left in a hurry with little more than the clothes on their backs.

Among the 1,000-plus items Muckle and the students have recorded are sake and beer bottles imported from Japan, gaming pieces, medicine bottles, clocks and pocket watches, teapots, buttons from clothing, coins, and hundreds of pieces of Japanese ceramics. And, unlike most archeological sites, many of the items were left undamaged.

“That’s very unusual in archeology,” Muckle said.

The skid road planks would have been valuable and could easily have been resold, but they were left in the earth.

The team found many pieces from cook stoves, mostly ones that would have been sold for a few dollars. But they also found one much more expensive one (about $37 in a Woodwards catalogue from the 1920s) that had been deliberately hidden on the periphery of the site, behind an old-growth stump.

“They were probably smart enough to realize people might loot the site,” Muckle said.

The archeologists also salvaged pieces of an Eastman Kodak Bulls-Eye camera, which would have been contraband in an internment camp.

“When people leave, usually they take all the good stuff with them,” Muckle said. “It all supports my hypothesis that people continued to live here until World War II internment because it’s really apparent to me, they just walked away from their little houses with a lot of good stuff in them. One of the last artifacts we found was actually the key to the house.”

It would have taken more than an hour to walk to the Lynn Valley bus stop, where the inhabitants could get to work in the city. That may sound unthinkable to today’s generations, but it was commonplace then, Muckle said.

The site would have plenty of fresh water, vegetables from the garden and fish from the nearby Seymour River. It must have been beautiful to live in the camp, Muckle imagines.

“The impression that I get, generally speaking, is it would have been a nice life for these people, especially in the context of all the racism in Vancouver in the 1920s and ’30s. The Japanese embassy was trying to encourage the Japanese to assimilate, primarily – don’t act differently,” he said. “The people who didn’t want to assimilate would have found refuge here.”

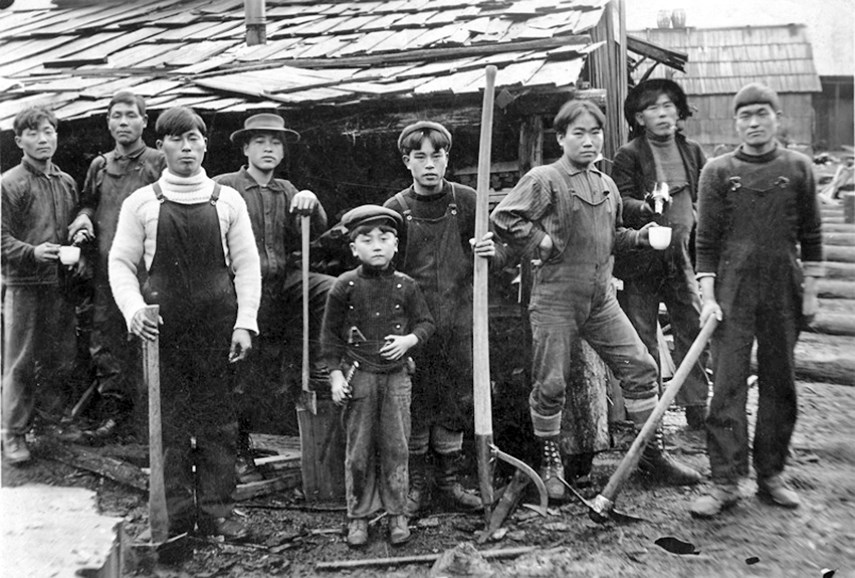

In its collection, the North Vancouver Museum & Archives has photos of Japanese loggers working on the North Shore dating back as far as 1905. Ide said she’s never come across any records that corroborate Muckle’s theory that people continued living there up until internment, but she said oral histories from descendants of Japanese immigrants might be a good starting point.

Still, Muckle has made a huge contribution to local history, Ide added.

“What he was able to establish is a part of history that wasn’t very well known for a long time and there were only bits and pieces of evidence,” she said. “That’s an important part about the wider story of immigrants that came to Canada and what their contributions were. … It also ties in deeply to the story of prejudice as well and what led to internment and why they’re not here anymore, why there is no Japanese community.”

BACK TO THE EARTH

In 2018, the District of North Vancouver awarded Muckle with a Community Heritage Award for his work in the Seymour Valley. But that work is now coming to its end.

“I’m thinking this is probably my last field season at this site. I’m thinking tomorrow is going to be the last day of excavation,” Muckle said during a visit in June, clearly having mixed emotions.

That doesn’t mean there isn’t more there. In fact, Muckle and his students only just found the foundations of two more houses in the last weeks of the dig.

And despite all the circumstantial evidence he and his students have collected, Muckle’s hypothesis that it remained a secluded Japanese community until internment remains just that: a hypothesis.

“I’m still looking for the smoking gun. I don’t have any artifacts that date clearly to post-1920 and that’s what I’m looking for,” he said.

It’s most likely going to be someone else who finds that confirmation though. Among archeologists, it’s considered unethical to excavate a site until there is nothing left. Technology may change, methods may improve, and different researchers may come back to seek answers to different questions.

“So, I haven’t ruined it for everybody,” Muckle said.

Muckle has plans to publish more scholarly articles as well as a book about the site, and he’s hopeful the Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre in Burnaby as well as the North Vancouver Museum & Archives will take possession of all of his records and some of the artifacts after he retires. That way, they’ll remain available for the community as well as future archeologists, “and in 100 years from now, or 10 years from now, they can see exactly what I’ve done.”

Metro Vancouver has offered to fence the logging camp, but Muckle has declined, worried it would only send the message to passersby that there is something important there, and invite looting.

The ferns will have grown back in just a couple weeks, hiding the Nikkei outpost once again, maybe this time to be reclaimed by the forest for good.