If you could choose, which pieces of North Vancouver’s past and its present would tell the stories of its people?

Would it be the double-ended Lonsdale streetcar 153, with its rattan chairs and wooden floorboards? Or mountaineering couple Don and Phyllis Munday’s climbing ropes? A haunting mask carved by Squamish Nation artist Sinamkin Jody Broomfield and the carving tools passed down by his uncle?

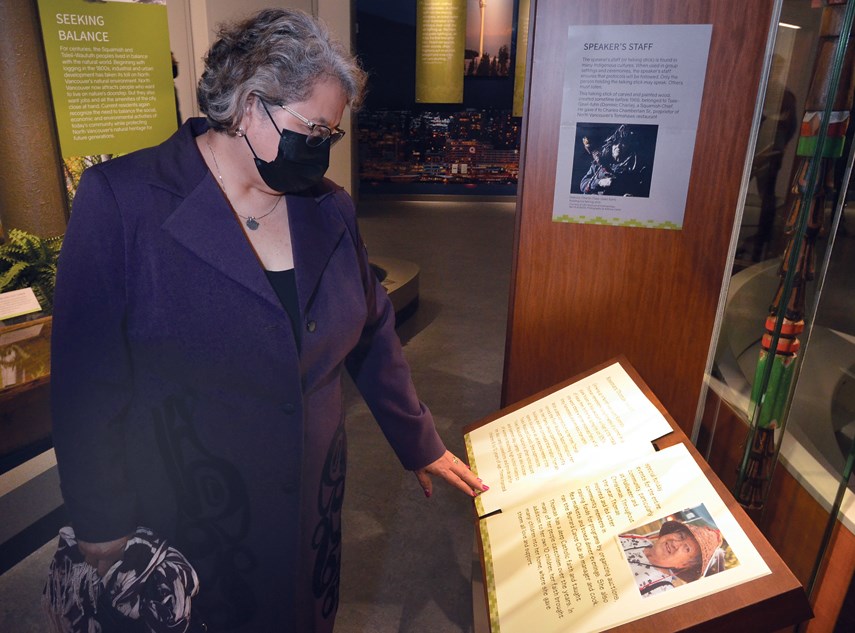

Those kinds of questions and answers are part of what’s behind the new MONOVA: Museum of North Vancouver, which opens to the public Saturday in its brand new Lower Lonsdale location at 115 Esplanade.

“There’s been a huge shift in museums in the last 20 to 25 years,” said Barbara Hilden, curator of the museum. “It’s no longer the curator or the institution that has the authority. It’s now a space for community members to tell their own stories.”

The idea of a museum has changed in other ways as well.

A museum, said Hilden and museum director Wesley Wenhardt, isn’t just about the past anymore. It’s also about how the past informs and shapes the present.

Objects on display are also not the point of a museum – it’s what they say that’s important.

The new museum space – in the heart of the bustling Lower Lonsdale Shipyards District – certainly reflects the museum’s philosophy of connecting with the present-day community.

When it opens to the public Dec. 4, it will mark the culmination of decades of planning for a new home. In 2016, the City of North Vancouver struck an agreement with developer Polygon to include 16,000 square feet of space in a new building on Carrie Cates Court for the new museum.

The $7.1-million museum was made possible by capital funding of $6.1 million from the federal, provincial and local governments, along with fundraising of $1.5 million.

An operating budget of approximately $1.5 million is funded 80 per cent by the City and District of North Vancouver, combined with money from the province, grants and revenues from rentals and a museum store.

Early on in the planning process, a connection to the land was one of the North Shore themes identified as key by the public. To acknowledge that, the entrance to the main exhibit space is through a short corridor that evokes the feeling of being in a forest trail, beneath a canopy of tall trees.

“We do it in an abstract way,” said Juan Tanus, exhibit designer from Kei Space Design.

The forest trail also solved a practical problem – “the fact the permanent gallery was on the other side of an elevator shaft.”

A welcome circle, introducing the culture and history of the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish Nation) and Tsleil-Waututh people is front and centre at the entrance to the permanent exhibit.

Reconciliation is one of the important roles of the new museum. That’s involved collaborating with Chief Janice George and Carleen Thomas, who co-chair the museum’s Indigenous voices advisory committee, along with Latash Maurice Nahanee, the museum’s cultural practices and policy advisor, on how the stories of their nations should be presented.

“So it wasn’t a white settler, like myself, coming in and identifying what needed to be told or what resonated with me,” said Hilden. “It was the Nations saying ‘This is what’s important to us. And this is how we want to represent ourselves.’ ”

Key to that is a recognition that Indigenous culture on the North Shore is still very much alive, and not part of a historical snapshot, said Wenhardt.

The pain of traumas ranging from smallpox epidemics to the residential school system aren’t glossed over in the museum, but at the same time there are recognitions of strong Indigenous voices including Chief Joe Mathias and Chief Dan George, and of modern-day economic developments such as plans for the Jericho lands.

Too often, “museums, as colonial institutions, have been really terrible at reflecting an idealized, lost narrative of these sort of noble cultures that are no longer with us,” said Hilden. In the new museum, it’s important to show modern Indigenous culture is still very much alive and thriving on the North Shore.

Other sections of the permanent exhibit recognize the significant role that more recent multicultural immigration has played in the development of North Shore communities, including significant arrivals of Iranians and Ismaili communities in the 1970s and 1980s following political upheavals in their home countries.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the North Shore’s long-held obsession with transportation is a significant theme, beginning with the first mass transit system – a three-line streetcar system that ran from 1906 to 1947 in North Vancouver.

Streetcar 153, one of the two centrepieces of the museum’s street-facing lobby, offers visitors a walkthrough of one of the original North Vancouver streetcars, while a video gives a sense of scenes the streetcar would have passed on its journey.

Car 153 was discovered, having been used as both a chicken coop and junk depository, in a farm yard near Chilliwack. Volunteers took on the task of lovingly restoring it.

Interestingly, at least one artifact used to tell the story of North Vancouver depicts things that might have happened, but didn’t. A model of a “twinned” Lions Gate Bridge found in a Burnaby thrift shop depicts one idea for solving traffic woes that was under discussion in the 1990s before being eventually rejected by the province. Small-scale replicas of the iconic lions sculptures originally created for bridge entrepreneur A.J. Taylor’s West Vancouver home are on display, as is a bridge truss from the original 1938 Lions Gate Bridge, removed during the replacement work on the main bridge deck 20 years ago.

Sports, arts and cultural touchstones all get their due in the new museum’s permanent exhibit – from a costume worn by “Canada’s sweetheart,” figure skater Karen Magnussen, to the stories of sprinting legend Harry Jerome.

The stories of modern heroes North Shore Rescue – which started as a team to assist in civil defence in the event of a Cold War nuclear strike – are also represented, along with artifacts from a mountain culture that dramatically predated the invention of Gore-tex.

Phil Nuytten’s famous North Vancouver-invented “exosuit,” which allows divers to safely descend 1,000 feet underwater, is also back in a place of honour, recognizing local innovation.

Interactive touch screens providing information in graphic form, and a sizable children’s section, round out the exhibit.

Not all artifacts will be found in the new museum. In recent years, the museum went through a significant process of shedding thousands of items that weren’t considered key to the North Vancouver story.

Some artifacts will be regularly swapped out for others in the permanent collection.

A temporary feature gallery with about 1,000 feet of additional space will also hold a rotating collection. The first of those “We are here @ the Shipyards” is expected to open in January 2022.

Not all stories can be told in the limited permanent collection space, said Hilden. But “we hope that there’s something in here that people will find interesting or see themselves reflected in.”

MONOVA opens Dec. 4 with free admission to the public on that day. The museum will be open four days a week, from Thursday to Sunday from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m.