A sensational murder case that shocked the North Shore more than two decades ago is getting a fresh audience this month with the release of The Confession Tapes, a new true-crime series on Netflix.

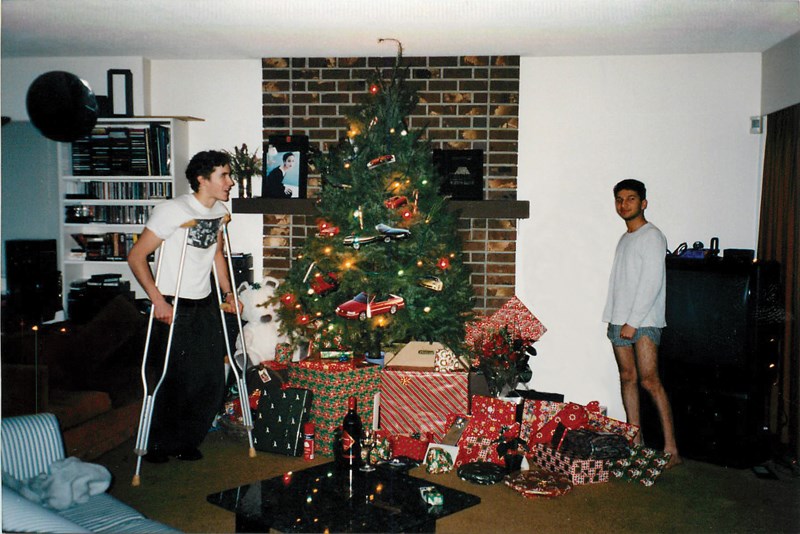

Los Angeles-based filmmaker Kelly Loudenberg focused the first two episodes of her series on the convictions of former North Shore teenagers Atif Rafay and Sebastian Burns, who are both serving multiple life sentences in U.S. prisons for the brutal triple slaying of Rafay’s mother, father and autistic sister in their Bellevue, Wash., home.

Loudenberg says she does not believe the men committed the murders, and makes a case for doubts in the new series, which focuses more generally on the issue of “coerced confession” through examination of a number of criminal cases in the U.S.

“A lot of people remember the case and have very strong feelings about it,” Loudenberg said this week.

“I would just hope it might help them look at the case differently and have an open mind.”

Burns and Rafay, high school friends who grew up together on the North Shore, had been staying with Rafay’s family at their Bellevue home when the all three members were violently bludgeoned to death with a baseball bat on a July night in 1994. The two men later told police they had been out at a movie at the time of the murder and came back to find the bodies of the Rafay family.

After the men returned to Canada, the RCMP conducted a sting operation, during which the pair confessed to the murders. After a lengthy legal battle, they were extradited back to the U.S. on the condition they would not face the death penalty.

Rafay and Burns were both convicted by a jury in Washington state of first-degree murder in all three deaths, largely on the basis of their confessions. They were sentenced to three consecutive life sentences. Two appeal courts later rejected appeals of the convictions.

Prosecutors have maintained over the intervening years that the right people were convicted, and that the confessions captured in the videotaped sting expose the pair’s true psychopathic nature. But others, including friends and family of the pair and advocates for the wrongfully convicted, have argued the two were young, scared and railroaded into making false confessions, that police investigators ignored other leads and that little other evidence directly linked the pair to the murders.

Loudenberg’s series weighs in squarely on the side of the doubters. “The public was given a certain narrative about this case early on which made it fairly difficult for any other narrative to be heard,” she said. “I think we really should talk about this case and what the facts are.”

Loudenberg, 32, learned about the case from Richard Leo, a U.S. law professor and expert on false confessions, who told her the case still troubled him.

During the two-year process of making The Confession Tapes, “this was the most expansive case we took,” said Loudenberg, who obtained investigative notes on the case from freedom of information requests to U.S. authorities as well as interviewing defence lawyers, prosecutors, jurors and experts on wrongful convictions and the controversial Mr. Big Scenario.

The two episodes on Burns and Rafay weave those interviews together with televised clips from the U.S. courts, footage from the actual Mr. Big tapes, audio from the 911 call and grisly photographs from the crime scene entered as evidence in the case.

Jay Straith, a local defence lawyer who practised on the North Shore when the Rafay and Burns extradition case went through the Canadian courts, said the Mr. Big confession remains the most troubling aspect of the case, regardless of the pair’s actual guilt or innocence.

One reason Mr. Big operations – in which undercover police acting as crime bosses ask suspects to confess their crimes so they can clean up the evidence – are illegal in the U.S. is that law authorities there are much more public with information about their investigations, said Straith. When a Canadian suspect confesses to details in a sting, often those are facts only the police would know, said Straith. In the U.S. those details are much more likely to have been widely publicized.

The cross-border nature of the Rafay/Burns investigation is therefore problematic, said Straith. In addition, “these guys were both really young at the time,” he added.

In 2014, a Supreme Court of Canada ruling put more restrictions on circumstances under which judges can accept “Mr. Big” confessions as evidence. “A court now would look at that through a different lens,” he said.

Loudenberg said she hopes her series will cause people to look at the case with a fresh perspective. “In my mind there’s plenty of reasonable doubt,” she said.

The Confession Tapes first aired on Netflix on Sept. 8.