In many ways, Vikki Harashchenko, 14, and Daryna Dyablo, 12, are typical teenagers. They can be shy, giggling easily as they consider their favourite Ukrainian pop bands or K-pop group BTS. But they’re also keen when describing the musical theatre production of Chicago they’re working on as part of Lights Up after-school theatre.

They can be silly one moment, serious the next.

When they’re not in school, the girls are usually together – skating at The Shipyards rink or hanging out at the library. Like a lot of teens, they practically live in each other’s homes.

But Vikki and Daryna have seen their country Ukraine torn apart by war in the past year and their families separated. Despite that, they remain remarkably resilient.

Normal lives upended by Ukraine war

A year ago, the two teens were strangers, living with their families in two cities in western Ukraine about 90 minutes apart.

Daryna lived in an apartment in Ternopil with her family, including sister Maria, mother Oksana, her father and brother. She took acting classes, performed in theatre and did gymnastics.

Vikki and her family lived in a Lviv, where her father, mother and grandmother all worked for the military.

Like a lot of Ukrainian families, before Feb. 24, 2022, they didn’t believe that war was coming, says Maria Dyablo, 23, Daryna’s older sister. “We didn’t believe it was going to happen, until the end.”

Daryna’s mother Oksana was preparing to present a business project in Lviv on Feb. 25.

But early in the morning, Feb. 24, Daryna’s grandmother called, saying, “Don’t go anywhere. War has started.”

In separate cities, both families packed emergency bags containing a few days’ supplies and tried to deal with the confusion of what to do next.

From shelter in church basement to Canada

When air raid sirens sounded later that evening, Daryna and her family made their way to a nearby church basement, where they spent the night with 300 others.

At first, neither family considered leaving Ukraine. Instead, Daryna’s family volunteered, helping at railway stations where refugees from eastern Ukraine were arriving.

Then Oskana’s sister told her about a new program opened by the Canadian government to fast-track visas for Ukrainians. Oskana, Maria and Daryna travelled to Poland to apply for a visa, leaving Daryna’s father and 23-year-old brother in Ukraine.

It’s a decision that still weighs heavily on Oskana.

In Canada, a Ukrainian church group connected them with a North Vancouver family willing to take them in.

In Vikki’s case, the connection to the North Shore started a generation earlier.

Lifelong friendship with Ukrainian woman

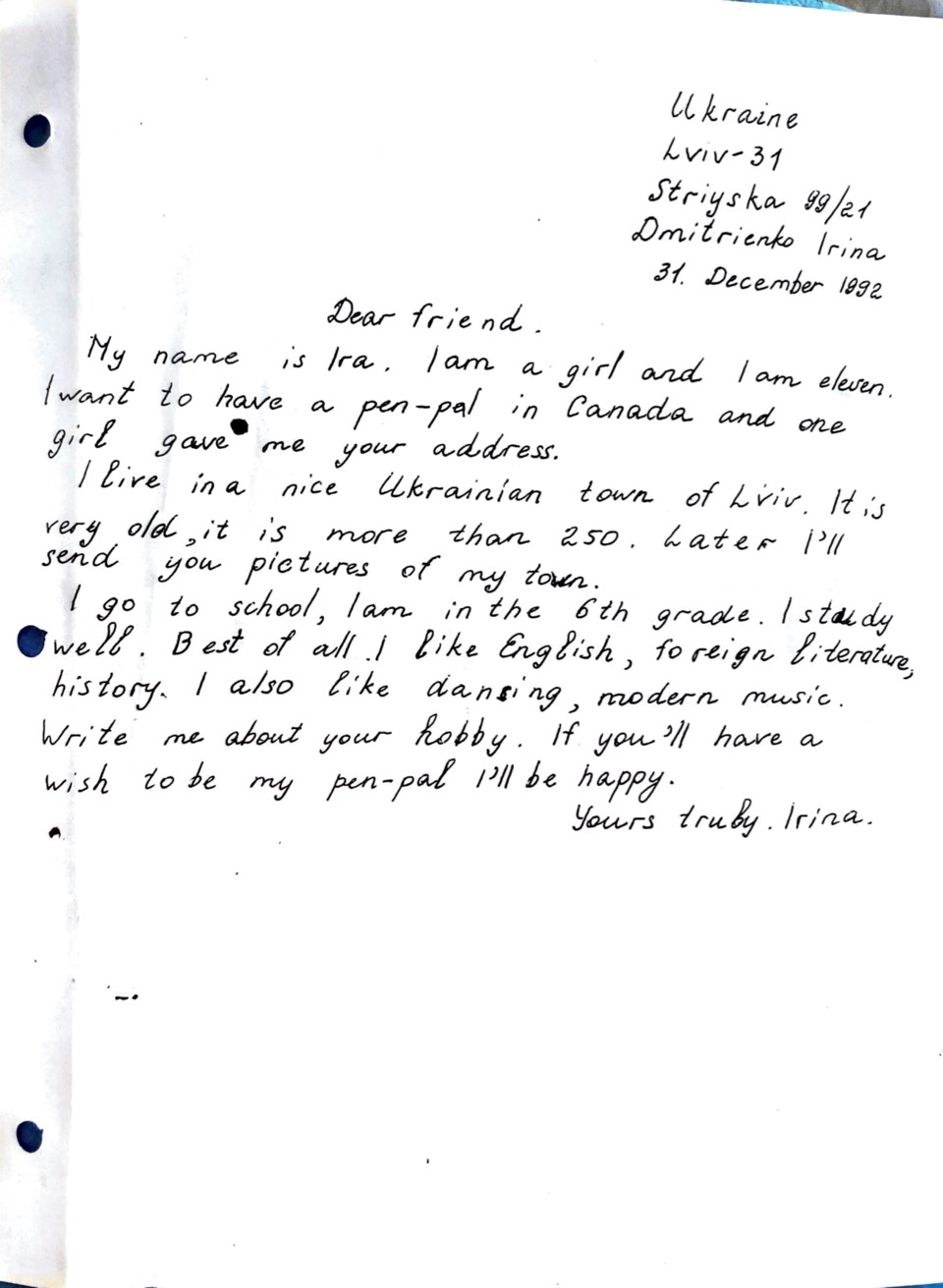

When Leanne Melnyk was 11, her dad’s Ukrainian newsletter put out a call for pen pals for girls in Ukraine. Melnyk wrote, and her letter ended up with a Ukrainian girl named Irina. A lifelong friendship began.

The two families visited each other often when the girls were young.

“I have a very vivid memory of us taking her to Lonsdale Quay and she was just amazed at the bananas and all the fruit because at the time, they didn’t have that in Ukraine. She was coming from a Soviet-standing-in-line-for-your-bread sort of background,” said Melnyk.

The friendship continued into adulthood. One of her visits to Ukraine happened just after Russia invaded Crimea, Melnyk said.

“I remember feeling very horrified that this invasion had happened and nobody seemed to do anything about it,” said Melnyk. “Ukraine was on their own.”

When the war started a year ago, Melnyk was worried. But Vikki’s mother was adamant she wouldn’t leave. “I remember Irina saying to me, ‘If everyone leaves, there’s going to be no one left to fight,’” she said.

After several missile strikes on Lviv, however, Irina agreed to let her daughter leave the country, accompanied at first by her grandmother.

Melnyk flew to Poland to meet Vikki, Irina and Iryna’s mother. At the time, Canada’s visa system was in chaos.

“I was really nervous they were just going to give up and go home,” Melnyk said.

It was an emotional time, with families saying goodbye to each other all around them.

“Vikki was silent through it all,” she remembers.

With their flight to Canada just a few hours away, “I went to the embassy and I begged,” Melnyk said.

She got the visas and they drove straight to the airport.

First Ukrainian student in her school

When Vikki arrived in North Vancouver, she was the first Ukrainian student in Braemar Elementary. The teachers made her feel welcome, she said, but there was still an adjustment.

Starting school was scary, says Daryna, adding she was worried about her English skills and about making friends.

School work in Canada is much easier than it is in Ukraine, both girls say.

They notice the mix of global cultures here they didn’t have at home and say most Canadians are friendly.

Vikki is now in Grade 8 at St. Thomas Aquinas, which has granted her a full scholarship, while Daryna is in Grade 7 at Braemar Elementary. Both girls get help learning English and are also continuing their Ukrainian studies online.

Little government help is provided for unaccompanied minors arriving from the Ukraine, says Melnyk. “It’s a really big gap in the system,” she said.

Neighbourhood is home to several Ukrainian families

Vikki and Daryna met this fall, when one of the Braemar teachers recognized the girls were roughly the same age, and mentioned it to both families.

It helps that they live close together in the same Delbrook neighbourhood, which is also home to several other Ukrainians who have fled the war.

Daryna’s sister Maria works at a local coffee shop, while her mother works babysitting, and hopes to train for work in a daycare.

Last summer, Vikki went home to Ukraine for two months to visit her family. Some of her friends are still in Lviv, others are in Poland and a few families have moved to safer areas, she said.

Melnyk wasn’t sure if Vikki would return to Canada in the fall, but the teen urged her mother to let her come back.

To stay in touch, Vikki talks to her mother every morning on the phone – when it’s evening in the Ukraine – except when the power in Lviv has been cut.

Teens don’t dwell on horrors of war

Though it’s impacted their lives profoundly, the girls prefer not to dwell on the war back home, says Melnyk.

Vikki and Daryna prefer to look ahead, hoping they’ll have a chance to go to high school together in North Vancouver next year.

For their families, the choices are more complicated.

But for the time being, “They just want to be teenagers,” said Melnyk. “There is a semblance of normal.”