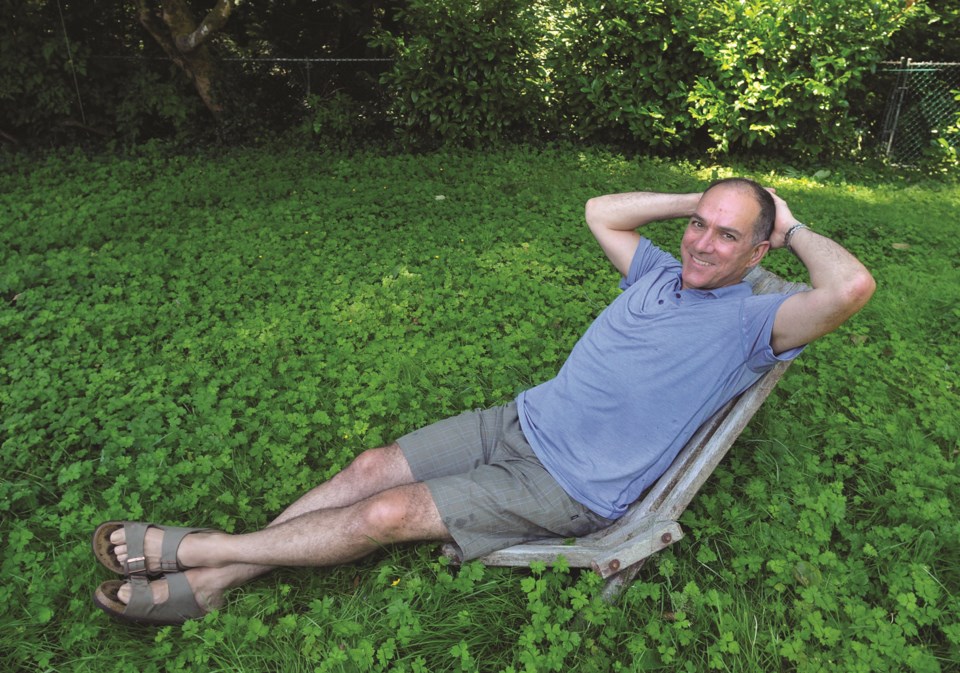

Greg Robins was something of a “lawnmower man.”

"I used to come out here once a week and just turn it into basically Par-3 golf course,” he said, gesturing to his Lynn Valley backyard.

It looked pretty, he said, but it was lacking something. In fact, apart from the grass, it was pretty devoid of any life at all.

Today, his backyard along the Hastings Creek greenbelt is blanketed in a verdant patch of ranunculus leaves – more commonly known as the weed buttercup. Elsewhere, there’s clover. But it’s also literally buzzing with bees and other insects.

Wild lawns

Robins is letting his yard “go wild.” It’s a growing trend (pun somewhat intended), among people concerned about the environmental impacts of our obsession with manicured lawns.

“I'm worried about our planet. I'm worried about the loss of habitat and the loss of fruit for insects and the decline in insect populations,” he said. “I'm concerned that if we don't turn our own little patch of grass into a home for a certain number of insects and bugs, we're going to be in trouble.”

The lawn is green enough you might mistake him for a “grasshole” – someone who turns the sprinkler on their yard even when it’s against Metro Vancouver’s watering restrictions. But Robins hasn’t watered at all this year. He has mowed a few times in a few spots where things were getting out of hand, which is actually what’s best for biodiversity.

A 2018 study published in the journal Biological Conservation found that being “lawnmower lazy” – mowing every two weeks – was optimal for attracting pollinators to yards in Massachusetts.

It’s a different look, but Robins said he can’t identify many drawbacks to the decision – although he concedes it’s harder to spot where his dog Luna has left something for him in need of scooping.

Unhealthy roots

Our obsession with manicured lawns is no more natural than the lawns themselves, said Terry Sunderland, UBC professor of forestry.

“The green lawn has its roots in wealth, privilege and colonialism … and the American dream of the '50s, which was predominantly white, moving into a house in the suburbs with a lawn and picket fence,” he said. “We’re just beyond that now, I think. I think we need to think more about resource use and the stuff we put on the ground, and think more about biodiversity. We've lost many, many of our pollinators because of that obsession with the bowling green type lawn.”

In the U.S., manicured lawns make up about two per cent of the land but they account for 60 per cent of the municipal water use, he noted.

Urban meadows

Sunderland has been an advocate for fostering “urban meadows” but there’s more it than simply being lawnmower lazy. Left alone, it’s likely that only one or two weed species will thrive at first. If you really want to kick-start some biodiversity, packets of wild meadow seeds would be a good start, he said.

“Over time, that will increase, and you'll get colonization from other species coming in,” he said.

Sunderland also said it’s totally appropriate to plant woody species like buddleia, lavender or rosemary along the periphery of a yard, which will attract happy pollinators without casting too much shade on the rest of the species trying to grow.

And you do have to manage the space and be ready to fend off invasive species like blackberries and Japanese knotweed, which will be more than happy to take advantage, Sunderland added.

Local and regional governments could lead by example and start swapping their own manicured lawn space for planned meadows, he said.

“It's great for biodiversity. It's great for pollinators. It's great for drought conditions, when water is scarce,” he said. “It can only be a good thing.”

Not everyone may be keen to have their neighbour commit an act of suburban landscaping rebellion, though, no matter the environmental benefits. A friend of Sunderland’s attempted a wild meadow, but in the first year, nothing grew but dandelions, which then spread to his neighbours’ garden.

“Which they weren't very happy about,” he said.

Luckily, the folks who live next door to Robins have been on board with his wild lawn. It’s something he’s hoping a few other folks will adopt in the summers ahead.

“I sit out here and I listen to the endless cacophony of weed whackers, lawnmowers and leaf blowers and wonder: could we not eliminate much of that noise pollution and air pollution and provide a home for our little critters that we need so badly?” he said.