On a chilly and damp March afternoon, Darren Guild and Ken Falconer chat with a group of men outside the North Shore Bottle Depot on Donaghy Avenue.

The two have yellow buttons pinned to their jackets indicating they are volunteers in the 2017 Homeless Count, a Metro Vancouver Regional District initiative being run by the BC Non-Profit Housing Association to get a snapshot of the Lower Mainland’s homeless population.

For 24 hours, volunteers armed with pens and surveys fan out around the Lower Mainland to meet face to face with people “living rough.” The results of the street census are intended to be used for shaping policies to combat homelessness.

Guild took at two-hour shift starting at 5 a.m. walking around Norgate Park, under the Lions Gate Bridge, through Bridgman Park and the wooded areas along Lynn Creek.

While he didn’t find anyone on the street or under a bridge, there was plenty of evidence someone had been there recently, Guild said – shopping carts and bicycles or makeshift cardboard mattresses left abandoned.

The last time the count was done in 2013, volunteers found 119 people living homeless on the North Shore. The total numbers from across Metro Vancouver from this year’s count won’t be available for a few weeks but both Falconer and Guild are predicting the numbers from the count will be down in 2017.

That, however, belies what they know to be true from their work in the non-profit sector. Activists and professionals who deal with homeless people on the frontlines say the 24-hour snapshot is probably just the tip of the iceberg.

“Things are way worse today than they were three years ago,” said Falconer. “What we’re seeing is more seniors presenting as being homeless. We’re seeing more people living in vehicles. We’re seeing more people who are living hard on the street and in tents.”

To be counted, someone must first be found by the volunteers and be willing to fill out a survey. Many would rather not be found. Many opt to not take the survey because it asks some deeply personal questions, including things like whether they identify as transgender.

Conducting the survey in March also means homeless people will call in favours to get inside.

“That’s what it seems to suggest to me because normally I certainly do see a lot of people sleeping rough in the area,” Guild said.

Others, Falconer said, reject the notion that they are homeless, arguing that their situation is just temporary, that they’re just between apartments, that they’ve got something lined up for the future.

“There’s a lot of denial, a lot of self-deception. They just don’t want to acknowledge it because there’s such a level of stigma attached to being homeless, and especially in an area like North Vancouver where there’s a great deal of prosperity,” Falconer said.

North Vancouver RCMP members also perceive actual homelessness on the rise. Oftentimes, officers are called to help break down ad hoc homeless camps that crop up in wooded areas.

“Camps or shelters … are on the increase. It’s often the public that advises us that they’re in the park or creek bed area. They get dismantled either by the city or the district. These people are living there out of necessity. They truly are. They’ve tried, perhaps, some additional supports,” said Cpl. Richard De Jong, North Vancouver RCMP spokesman.

“We don’t want to just tear things down and leave people more destitute so we’ll try to get them into a place like the Lookout (shelter) or connected to services that can be of assistance to them.”

Although there appears to be more people of all age groups, the RCMP is also noticing more seniors, De Jong said.

“Which is always heartbreaking because they are less resilient to the weather and the hardships of living on the street.”

There are any number of tipping points that put a person on the street: The loss of a breadwinner’s income, the death of a spouse, renoviction, demoviction. And often there are other more challenging underlying issues – mental illness, addiction, unemployment, family abuse.

Under B.C.’s welfare system, recipients only get $375 a month for their housing budget, a number that hasn’t budged in years. To supplement, people on welfare have to find other ways to make ends meet.

“That’s why I’m here every day, trying to make a couple bucks,” said a man outside the bottle depot who goes by the name One-way.

One-way didn’t want to take the survey because of its personal questions. He didn’t mind sharing how he wound up on the street however.

“I got kicked out my house on the reserve because I was the No. 1 dealer and well known. Too much activity at my house. Too many fights and all that bullshit so the band asked me to step aside and I did because I was tired of it myself. I’ve been at the shelter ever since,” he said.

That was about seven months ago. It’s been a cold winter to spend most of his time outside, One-way said, but he still opts to spend a lot of his time away from the shelter where conflicts frequently arise.

“Everybody’s got their problems,” he said.

Beyond those living rough, there’s an even larger population living at imminent risk of being homeless.

“Eighty per cent of Canadians are only 12 weeks away from actually needing to access services like a food bank if they were to lose their job,” said Falconer. “We spoke to one person today who is clinging. We couldn’t count him but he knows he’s only weeks away from being homeless.”

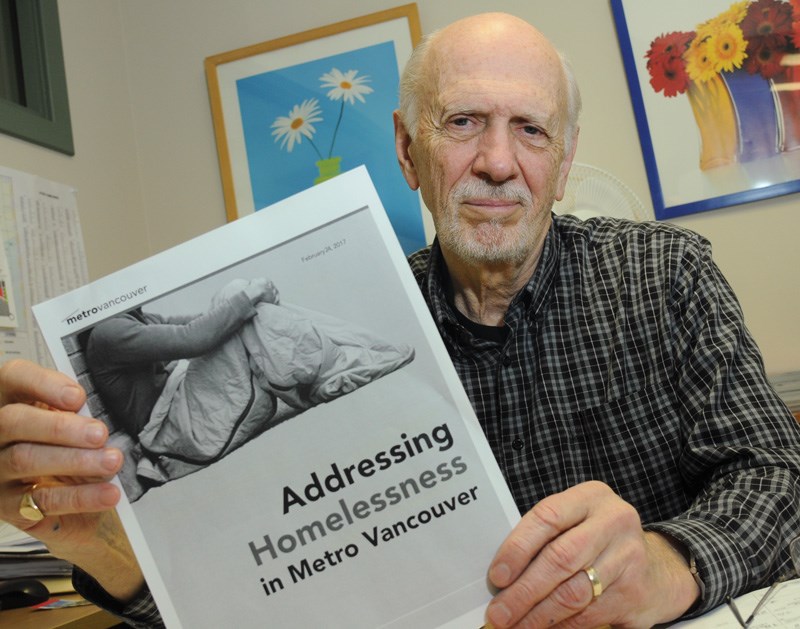

That’s something Don Peters, chairman of the North Shore Community Resources’ community housing action committee, sees all too much of.

“I get so many people in here who are terrified. Just terrified,” he said.

A 2016 study found 8,990 households on the North Shore, 13.6 per cent, are experiencing “core housing need” – that is, they are spending more than 30 per cent of their income on housing alone. Half of them are spending more than 50 per cent.

But regardless of how someone wound up on the streets, Falconer, Guild and Peters are in agreement, it’s a lack of affordable units being built that keeps them there.

“As a region, we’re going in the wrong direction. We are not improving this situation. I don’t think it’s overstating to say that lives are at risk,” Peters said. “The last I heard, there were over 10,000 people in one situation or another on BC Housing’s wait list.”

Peters is front and centre whenever any of the three local councils is debating a project that has an affordable housing component, even if it’s just market rental units, which the private sector essentially stopped supplying when federal subsidies were cut 30 years ago.

But while we could be buying prevention by the ounce, we’re buying cure by the pound, Peters suggested. We spend massive amounts trying to mitigate the impacts of homelessness when it would probably be cheaper to get people into apartments.

“The financial cost of maintaining the current homelessness approach is staggering. If you step back from Canada, it’s about $7 billion per year,” he said. “In the region, it’s about $55,000 per homeless person when you factor in all of the services, the involvement of the police and ambulance and all of the emergency wards and even courts and this horrible overlay of the drug epidemic. I have no idea how you get at the cost of that but it’s horrific.”

Guild agrees.

“It’s hard to stabilize when you don’t have food in your stomach, you don’t have a place to live, nowhere to sleep. That’s a tough place to start. I think that having shelter leads to a lot more success for a lot of people,” Guild said.

Metro Vancouver has adopted the “Housing First” approach to dealing with homelessness and its array of spin-off problems, but municipalities only collect eight cents out of every tax dollar in Canada, leaving them at the mercy of senior levels of government to fund new affordable housing units like they once did.

Last year, the province announced $500 million for affordable housing projects, although none of the money is earmarked for the North Shore.

Similarly, the federal Liberals promised the return of a national housing strategy but on the eve of the feds’ second budget, there have been no details released.

“We’ve got to get an increase in the affordable rental housing supply. We’ve got to support municipalities who are trying to retain buildings that are at risk of demolition and get them to push hard to contribute land for the construction of new units through the provincial program,” Peters said.

In order for there to be the political will for change, North Shore residents first have to confront the problem for what it is, rather than stay willfully blind to the man sleeping in an alcove, Falconer said.

“How we look after the worst and the poorest people in our community really speaks to what a community we are and I think we need to look at ourselves when we look at that,” he said, holding back tears.

With an election coming up, there’s no better time to send the message to politicians that we find this unacceptable, Falconer added.

“It’s unacceptable for people to be sleeping on the streets. It’s not acceptable that people who have health issues around addiction are dying. It’s unacceptable. We need to have this change. If we look at this provincially, federally as well as locally, we can do something. Not today. Not tomorrow. It’s going to take a long-term vision but we need to have that long-term vision and be prepared to make those changes now.”