The North Shore has lost a modern master.

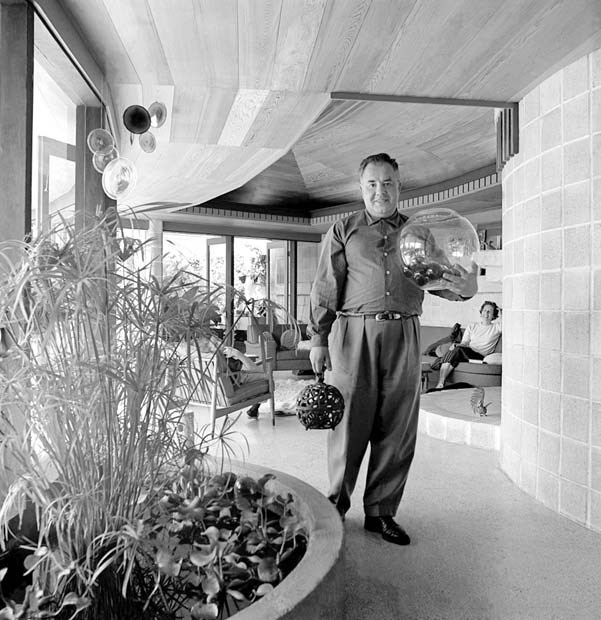

Fred Thornton Hollingsworth, the architect who helped pioneer West Coast modernism and shaped the post-war look of residential North Vancouver, died April 10 at the age of 98.

Hollingsworth leaves a legacy both philosophical and physical. Many of the homes he designed are still standing, including the residence in Edgemont Village he designed for his family in 1946. It’s where his son Russell grew up.

“It was very, very small. Very simple. It was the first house he designed before he became an architect,” Russell says of the originally 1,100-square-foot, one-bathroom house that accommodated their family of five.

That house launched Hollingsworth’s career. He articled with Sharp & Thompson, Berwick, Pratt and later became an associate at W.H. Birmingham. He partnered with architect Barry Downs in the early ’60s and ran his own firm from 1966 onwards. He designed mainly residential homes, many of them on the

North Shore, but some larger buildings as well such as UBC’s Faculty of Law building.

Hollingsworth was a busy man in the post-war years, moonlighting constantly.

“He was not your average TV dad,” says Russell, also an architect, “but he taught me a lot about working with my hands, and about art and culture and architecture and philosophy. We were steeped in that kind of an upbringing.”

Born in England in 1917, Hollingsworth moved to Canada with his family when he was 12. A talented musician, painter, sculptor and draftsman, Russell describes his father as a “Renaissance man.”

“He was a real craft-oriented person. He did all his own drawing and was not an executive-type architect, but a real working man’s architect.”

Father-son time was often spent visiting construction sites and, though Russell never intended to go into architecture, “it just happened by accident.”

Hollingsworth was a disciple of Frank Lloyd Wright. Inspired by Wright’s organic design principles, he and contemporary Ron Thom were among the earliest initiators of the West Coast style, making use of natural materials at a time when steel and concrete were hard to come by. “They had very horizontal lines and they were based on open plans, which was very different from most housing,” Russell says.

As architectural writer and curator Adele Weder explains, Hollingsworth developed the neoteric style of house based on an easily replicable template.

“They all have the same kind of DNA, but they’re customized for each client, so it’s sort of the best of both worlds. You don’t have that mindless repetition of tract housing, but you don’t have the wastefulness and exclusivity of having a completely different home for every client.”

What really sets a Hollingsworth house apart, she says, is the craftsmanship and the humanity he injected into his work. “Sometimes modernism can be overly rigorous, overly rational. Fred’s work, though modern, was always organic and always had a sense of playfulness.”

In that sense, Hollingsworth’s character was reflected in his designs.

“He had a great sense of humanity about him and an unbelievable sense of humour,” Russell says. One of his father’s greatest strengths, he adds, was creating homes for working people of modest means.

“He didn’t seek out or have really wealthy clients. He was a very egalitarian-minded kind of person and believed that good design shouldn’t be exclusive.”