It’s been more than two years since the Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure’s $200-million Lower Lynn Improvement Project wrapped, ending a multi-year project to ease the North Shore’s notorious congestion.

But has the project helped improve traffic flows? The answer depends largely on where you’re driving and when, according to a 2023 before-and-after performance study, commissioned by the ministry and provided to the North Shore News.

The study used stats from 2018 and 2022, including data from smartphones, specially placed radars and the ministry’s own traffic counters to estimate travel times and speeds from Lynn Valley Road to the south end of the Ironworkers Memorial Second Narrows Crossing. To zero in on typical commute times, the study looked only at weekday travel, omitting stat holidays.

Traffic data shows a nuanced picture

The study found travel times and speeds and reliability of the highway improved significantly for commuters through the Lower Lynn Improvement Project area during the morning rush hour, regardless of which direction they’re travelling in. Drivers headed down The Cut moved 56 per cent faster between 7 and 8 a.m. in 2022, for an average of 82.5 kilometres per hour.

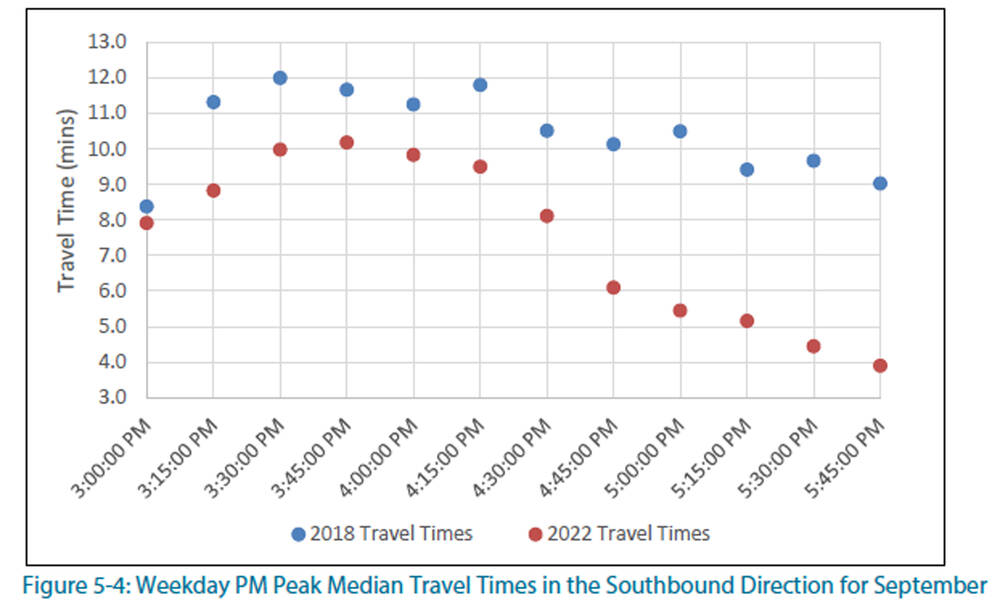

The infamous afternoon Cut traffic though did not show the same results. Between 3 and 4 p.m., average driver speeds fell by four per cent to 22.1 km/h, the study found. Between 4 and 5 p.m., there was an eight per cent improvement to an average of 24.1 km/h.

“The observations from the p.m. peak period suggests that overall, there are minimal changes in travel speed along this segment, however the best commuting days have increased moderately in speed for 2022,” the report states.

The report adds that the improvements in speed could possibly be attributed to the new Mountain Highway off-ramp, giving drivers headed for Keith Road a new, easier option.

Other metrics, however, showed the afternoon drive towards the Ironworkers had improved. In 2018, the average time it took to drive the length of the project corridor peaked at 12 minutes. In 2022, that had fallen 15 per cent to 10.2 minutes. And the highway was noted to take less time to “recover” back to normal traffic flows, effectively ending rush hour earlier than it would in 2018.

The number of collisions in the corridor also fell significantly in the two years examined in the study. Between January and October, 2018, there were 52 crashes. In that same time period in 2022, there were just 20. One of the goals of the project was to improve safety by reducing the number of short merges and weaves built into the interchanges.

To read the entire report, click here.

Was it worth it?

The report does attempt a high-level cost benefit analysis accounting for time saved during the weekday rush hours, thanks to the project, which was first conceived of and funded under the BC Liberals in 2014, with the District of North Vancouver and federal government sharing in the costs.

Collectively, the analysis estimates a daily cost savings of $24,000, based on time no longer spent in traffic, or $5.9 million per year, for the $200-million project.

Although the study’s authors warn that more data may be required to understand longer-term collision rates, the report finds about $6.5 million was saved in injury costs and property damage when factoring in the number of crashes that occurred per kilometre driven.

Because of the increases in efficiency, the report estimates carbon emissions from drivers’ vehicles through that stretch have been reduced by 10 per cent in the morning and five per cent in the afternoons.

The report did note that the average number of weekday drivers passing through the corridor was 120,000 in 2022 – still about 4.5 per cent lower than it was in 2018, a possible function of more North Shore employees working from home. During that time period, average volumes on weekends were up by two per cent.

Rapid transit is the answer, North Vancouver MLA says

North Vancouver-Lonsdale MLA Bowinn Ma acknowledged that some improvements had been made but she said, that may be cold comfort for drivers who still have a very frustrating experience in today’s traffic.

“Congestion is a very human experience and it’s very emotionally driven,” she said. “So, the data may show that people are getting to where they need to go faster and with more consistency, but it likely won’t feel that way when you’re actually behind the wheel.”

Ma said the biggest win from the project has been the decrease in collisions.

“Not only from a safety perspective, but also in the experience of drivers,” she said. “It creates an incredibly unpredictable environment for commuters.”

If the North Shore wants less car congestion, Ma said, a better strategy would be to find a way to house people who currently commute here via Highway 1.

“Because, whether or not people are living here, they are working here,” she said.

The Ironworkers Bridge still has decades of life left in it but Ma said planning work for its replacement has already begun within the ministry. That new bridge though should be seen primarily as a rapid transit link, not just a means to get more cars on and off the North Shore, she added.

“If we were to add additional car lanes onto a bridge across the Burrard Inlet, those cars would simply get jammed up in our local streets,” she said. “We also know that induced demand means that that extra space will be very quickly filled up by additional commuting, and we’re going to see additional commuting if you don’t resolve our housing affordability challenge, particularly in light of increased population across the region.”

North Vancouver mayor not surprised

Mayor Mike Little said study reveals some answers about traffic patterns today, but it also indicates more work will need to be done to address congestion on the North Shore.

“It shows that there was some progress and some benefit, which we all saw there was going to be when you better manage eight lanes of traffic down to three,” he said. “But it doesn’t get an extra person over the bridge and so that’s still to be to be determined.”

Little said no one in government was expecting the project to be a silver bullet for North Shore traffic but the data showing improvement does align with his personal experiences commuting from his own neighbourhood.

“We definitely knew the limits of what it was going to improve because it wasn’t going to address the bridge deck. But there’s no question that it has improved reliable access to and from the Seymour area,” he said.

When traffic is at its worst – days when a stall or collision has closed one lane of southbound traffic on the bridge – Little said there is still work to be done.

“The clearance time for collisions on the bridge is still extremely long,” he said.

Little added that although study was “data rich” in how it analyzed driver stats within the Lower Lynn Improvement Project corridor, it did not reveal at all where the traffic was coming from or why.

“While it does address some of the performance issues, in my view, it doesn’t address the demand side, which is historically long line-ups on both sides of the bridge at different times of the day, and it’s seven days a week,” he said.