After serving 29 years in prison for a car-jacking murder he didn’t commit, recently exonerated Brooklyn native David McCallum was busy making up for lost time with family during the holidays.

But he still planned to make time to write to Atif Rafay, the West Vancouver man serving three consecutive 99-year sentences for the murders of his family – father and mother, Tariq and Sultana, and sister Basma – in 1994.

McCallum, freed in 2014, and Rafay share disparate backgrounds, but their lives intersect in many curious ways.

McCallum grew up in a crime-ridden New York neighbourhood and was wrongfully convicted of the kidnapping and murder of a 20-year-old man in 1985. He was 16 at the time and sentenced to 25 years to life.

Rafay was an 18-year-old freshman at the Ivy League’s Cornell University when he was arrested and charged, along with best friend Sebastian Burns, for killing his family inside their home in a quiet Seattle suburb. The pair was convicted in 2004.

What connects their stories is the spectre of false confessions and a Vancouver man named Ken Klonsky of The Innocence International. The prisoner advocacy group was founded by Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, the falsely imprisoned boxer made famous in the Bob Dylan song “The Hurricane” and later in a movie of the same title starring Denzel Washington.

After spending 18 years in prison for a triple murder in New Jersey he didn’t commit, Carter was released in 1975.

Klonsky, a retired teacher and writer, invited Carter to speak to his students and the former middleweight boxer agreed to visit his classroom.

Klonsky later wrote a magazine article about Carter’s plight. McCallum, who was convicted of the crime along with his friend Willie Stuckey, read the story while in prison and sent a letter to Klonsky asking for help proving his innocence. Klonsky agreed and began poring over transcripts and court documents and soon came to believe two innocent men were in jail. That turned out to be Klonsky and Carter’s first innocence case. His second, the case of Burns and Rafay, came five years later.

“These were coerced confessions in both cases. Each with two (sets of) teenagers. They were both coerced but were coerced in different ways,” said Klonsky.

Klonsky has said that selecting the right cases to pursue is absolutely critical for innocence projects because one mistake can destroy a group’s credibility.

Klonsky advocated for McCallum’s innocence for a decade, visiting him in prison, regularly talking by phone and working with a pro bono legal team to prove his innocence.

When Klonsky’s teenage son Ray was getting in trouble, he had McCallum write him a letter and the two began corresponding.

After graduating from film school, Ray and classmate Marc Lamy began shooting a documentary titled David & Me, in which they participate in the improbable quest to free McCallum alongside a group of lawyers and detectives.

Ray and Lamy spent seven years on the project and happily re-cut the ending of the already completed film after McCallum was exonerated and released from prison in October 2014 at age 45.

McCallum’s release came following a deathbed op-ed piece in the New York Daily News written by Carter pleading for the exoneration, which came too late for the co-convicted in the case, Stuckey, who died of a heart attack in prison in 2001.

According to a press release from the Office of the Brooklyn District Attorney, a review of the case “concluded that the confessions were false and not supported by physical or testimonial evidence.”

Klonsky described McCallum’s release as “the best day in my life, with the exception of the birth of my son.”

Since his release McCallum has been working at Manhattan Legal Aid Society and lives in Brooklyn with his mother.

The Visit

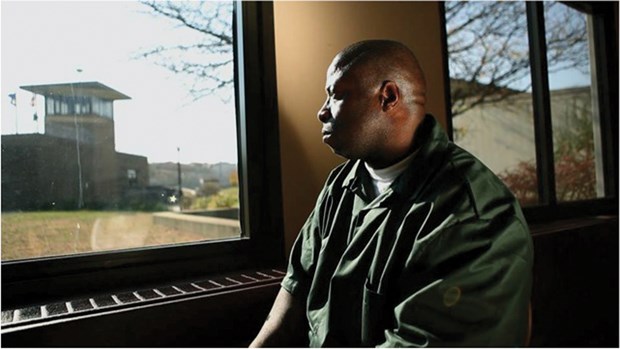

In September, David McCallum flew to Seattle to visit Atif Rafay at the Washington State Reformatory, a century-old brick prison that houses 700 inmates.

The hulking prison is fortified by tall walls ringed with barbed wire and guard towers, but McCallum wasn’t intimidated as he approached the visitors’ entrance.

“Surprisingly I wasn’t anxious, or nervous or anything like that,” said McCallum. “One of the reasons I really wasn’t going to be nervous about the prison was Atif. … I had gotten to know a lot about him prior to meeting him for the first time.”

When he first saw Rafay inside the prison’s cafeteria-style meeting room, he took note of his small stature and his intelligence.

“In some ways he kind of reminded me of myself in having to do your own legal studies and how knowledgeable you have to be about your own situation because no matter how many attorneys you have or supporters you still have to have a lot of knowledge about your own case.”

The pair sat across from one another separated by a small table talking about their cases and McCallum’s hard-fought freedom.

While their cases differ – “the notable exception, which is a huge exception, obviously was the fact that he lost his family,” said McCallum – there was common ground for the pair who grew up worlds apart.

“I think that one of the similarities that is very obvious is the false confession,” he added.

The Brooklyn man believes youth are particularly susceptible when it comes to being interrogated by skilled law enforcement officials.

“Manipulation is huge in interrogations, especially with young people. It doesn’t really matter how much you think you know or how smart you think you are or what your education level was at the time you were being interrogated – it really doesn’t matter when you are put under that kind of pressure you know,” he said. “And of course law enforcement knows this … and that’s what happened to me.”

Overcoming a false confession can be like driving up an icy mountain pass on bald tires and inevitably the question becomes: “If you didn’t do anything, then why confess?”

“Of course there are circumstances involved in why people confess. It’s called physical duress, it’s called manipulation, it’s called coercion, those sorts of things,” he said.

Burns and Rafay have always argued that they were coerced into confessing by undercover RCMP operators posing as underworld criminals in a controversial “Mr. Big” sting operation.

Life in Prison

After nearly three decades behind bars, McCallum understands what it takes to survive the daily monotony of prison life and remain positive while trying to prove your innocence, even in the darkest hours.

He says having a lifeline outside the prison walls is vital.

“It was everything to be honest with you. You’re inside but you have a lot of people on the outside working for you, believing in the cause in which everyone is fighting for, I know for me it’s a huge incentive to know that. I think Atif feels the same way. You know a lot of people on the outside believe in him. And I think that goes a long way towards a person’s morale,” said McCallum.

For nearly a decade, Rafay has been a student and TA with University Beyond Bars. Along with tutoring fellow inmates in calculus, composition, literature and philosophy, he’s also pursuing a BA in specialized studies in modern literary criticism and theory. While incarcerated he’s had several pieces of writing published, including an essay on personal freedom that was published in acclaimed Canadian magazine The Walrus.

“One of the things I know Atif does while he’s inside is he educates other inmates, which is always great to do because I know when I was inside I was a facilitator too for alternatives to violence programs and that sort of thing. Just being able to do that and share my story with other inmates to me in some ways was almost like therapy. Plus the fact that I was able to help other people out.”

Burns, meanwhile, is incarcerated at the same correctional complex in Monroe, but at a separate facility and the pair are forbidden to communicate.

McCallum said Rafay doesn’t need his help to motivate him in his quest for freedom – “he’s a very motivated man, obviously” – but he would share the same advice Rubin Carter once imparted to him.

“Rubin would always say: ‘Think about that hole in the wall and if you can see that hole in the wall, then that’s your path to freedom.’ It’s important to remember who you are and why you are there … and the fact that you know that you are not supposed to be there. And for me I hold on to that innocence – that was everything to me.”

Klonsky, who sat in on the visit between McCallum and Rafay, believes it was important for the pair to meet.

“I felt David was a symbol to Atif of possibility. David was in for 29 years and Atif’s case, well he’s been in for 20 years and a little more and that if David could get out, then perhaps he could.

And I think that was David’s message,” said Klonsky. “He had to stay the course, not give up on himself.”

In 2013, Washington state’s top court denied Burns and Rafay’s petition for a review of their failed bid in appeal court the previous year to overturn their triple murder convictions. Burns and Rafay continue to fight to overturn their convictions.

And while the cases have similarities, there’s also major differences, according to Klonsky: “In that we had three highly regarded professionals dealing with the case in New York. Plus we had private investigators. We weren’t dealing with the appeals process and that has made this whole thing much more difficult,” said Klonsky.

But with Innocence Project Northwest now involved with Rafay and Burns’s case that may change.

“(Our) lack in expertise they can easily make up for. And there’s a lot of energy in the group that’s helping Atif,” said Klonsky.

McCallum plans to keep in touch with Rafay.

“In fact I’m in the process of writing him a very long letter now just to let him know what I’m doing just to keep him positive and try to give him some information and some news to keep his morale high. If he continues getting the support he’s getting I’m sure he’s going to be fine,” McCallum said. “I’m sure he’s going to find himself out of that place sooner or later, it’s just a matter of staying the course and remaining positive throughout it.”

In an email to the North Shore News, Rafay wrote about what the visit from McCallum meant to him.

“It was inspiring to meet David. I’ve only met two people who have made it out alive from wrongful conviction: Rubin and David. Of course, Ken Klonsky kept me up-to-date with the progress of his exoneration, but until it actually happened I could never be sure that it really would. It was special to speak with him and share our not-nearly-unusual-enough experiences. He is courageously rebuilding a life that prosecution shattered, and seeing that he has done that successfully despite the sadness of all that he lost was very encouraging. I am very grateful to have him on my side. He gave me valuable advice and the hope not only that I can be exonerated, but that something can be done to remedy the pervasive error in the criminal justice system.”