When Ariel Wang got her first bike, one of the first things she did was take it apart and put it back together.

“I like to take things apart,” she says. Plus, in this case, “I really, really disliked the colour,” she says. “It had flowers on it.”

So she took it apart, spray-painted it a matte grey and put it back together. Problem solved.

Turns out, that approach to fixing and making things comes naturally to Wang, now 17.

When she joined the after-school robotics club at West Van Secondary in Grade 9, “she showed an aptitude right off the bat,” says teacher Todd Ablett, who runs what has now become the school district’s robotics academy. “It was obvious.”

Ablett isn’t the only one who thinks so.

Recently Wang, who graduates this year, learned that she’s been accepted into Harvard University’s prestigious mechanical engineering program. That acceptance comes with full financial backing of up to US$74,000.

Ablett says that’s a significant feat. “They want her there,” he said. “That’s what it means.”

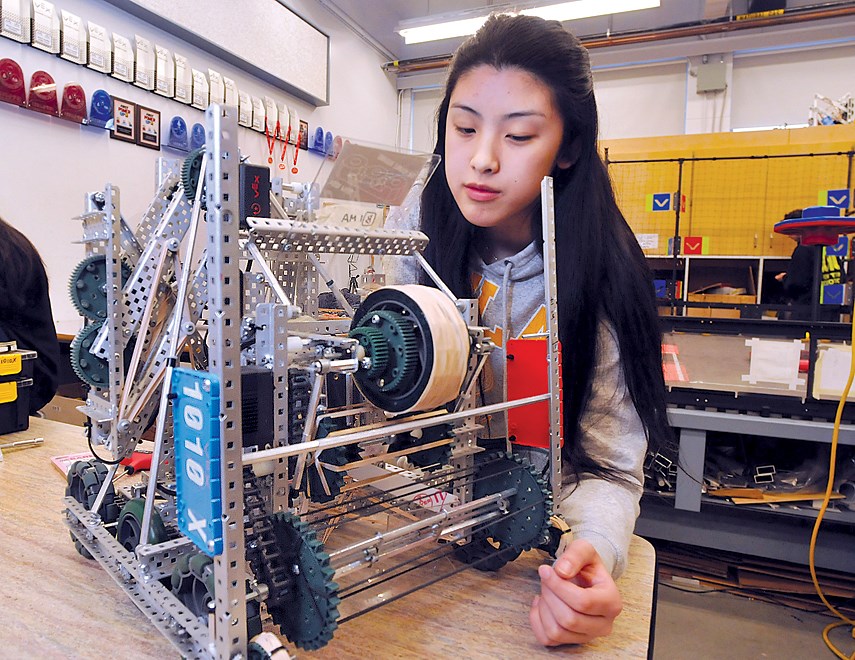

As part of the robotics club and later, the robotics academy, Wang has spent countless hours in the lab at West Van Secondary, designing, building and programming the VEX robots that teams from around the world put together to see whose will be best at specialized tasks.

The first time she was on a robotics team “we placed ninth, which was one spot away from qualifying for the world championships,” said Wang. She was hooked, and in the years since has spent many evenings at the high school, working on robots with her teammates, sometimes until after midnight.

Wang is matter of fact about the time she and other students put into their projects. “The quality of your robot is completely dependent on the amount of effort you put into it,” she says, adding if you want to win competitions, you can’t show up twice a week. “You have to be here every single day.”

Wang also combined robotics with a full load of academic courses for the International Baccalaureate diploma program – heavy on the sciences.

It’s a rigorous program, but one she hopes will prepare her for Harvard. “I like being with people who challenge me, and who have the same sort of drive as me,” she says.

When she started with robotics, Wang was one of only two girls who were part of the club. Those numbers have since grown, but Wang says she’s never felt being a girl in a male-dominated field was a problem.

“All my peers were really accepting,” she said. She especially credits an early robotics teammate – since graduated – who encouraged Wang to be the person who drove the robot at competitions.

“That was kind of unusual to see,” she said. “You didn’t really see girls driving.”

These days, Wang talks as easily about using drive programs and controllers to optimize motor output as she does about using CAD programs to design the robot parts.

“I think the building process is my favourite, because it involves so much creativity,” she says. “There’s no right way to build something. There’s only a better way to build something. Part of building is recognizing what you’ve done wrong and how to fix it.”

That happens a lot, she says, looking around the lab.

“Every robot you see here hasn’t been built once. They’ve been built at least five or 10 times until they work the way you want it to.”

That determination is one of the attributes that’s helped propel Wang to Harvard, says Ablett.

“She’s pretty fearless about failure,” he says.

“She fails as much as anyone else. It just doesn’t stop her.”