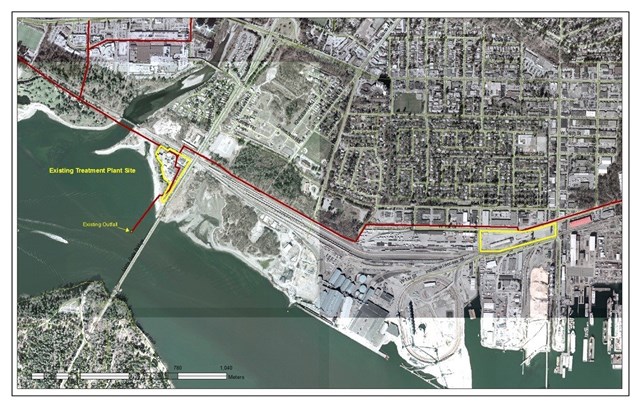

Amid the currents of the First Narrows underneath the Lions Gate Bridge, the outfall for the North Shore’s 58-year-old sewage treatment plant dumps over 30 billion litres of waste into Burrard Inlet every year.

It’s out of sight and out of mind. We can’t see the suspended nitrogen and phosphorus or the way breakdown of waste uses up oxygen in the water. We can’t see the Prozac, the hormones and the painkillers we put into our bodies and flush down the toilet, into the environment.

But the salmon swim through it, and so do the whales.

For one group of North Shore environmental crusaders, though, what we can’t see has never been far from the surface.

Now, six years after their fight began to get government on board with an advanced level of sewage treatment, there are signs of hope, at a time already well past the eleventh hour.

Despite a design-build contract already in place to construct a new secondary treatment plant, reliable sources – including emails from top Environment Canada regulators obtained by the News — say behind closed doors Metro Vancouver politicians are already on their way to doing a serious rethink about tertiary treatment and recently voted to up their environmental game, provided federal and provincial governments also come on board.

North Shore environmental advocates aren’t cracking the champagne yet.

“These are big dollars and they’re not small decisions,” said Glen Parker, a board member of North Shore Streamkeepers, who has been among those leading the push for tertiary treatment in the new plant. But he adds, “I would say I’m more optimistic now than I was a month ago or even two weeks ago.”

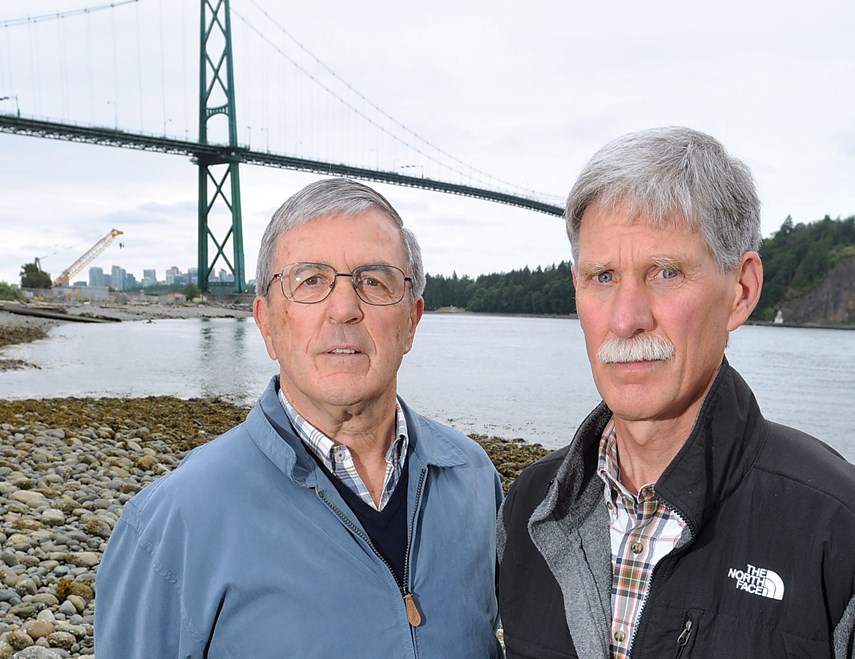

Some of the key North Shore figures in the fight to get Metro to clean up its act are at first glance unlikely environmental warriors – engineers with plenty of experience working on projects within “the system.”

But they are also – to paraphrase – poop disturbers.

And they recognized when a perfect storm of biosolids recently presented an opportunity.

Among the contributors: science pointing to harm to marine life, and both financial and political incentives.

Ironically, it was the project contractor Acciona getting slapped with a stop work order from the District of North Vancouver – shutting down work for three months – that really opened the floodgates.

Where some saw massive infrastructure headache, Parker saw his chance. “When a project is in trouble, there’s often a renegotiation,” he said. “There’s your opportunity.”

The fight over what to replace the aging primary treatment plant with goes back many years.

For decades, the waste being flushed into Burrard Inlet through an outfall deep below the surface has been treated to only a very basic “primary” level – which essentially involves taking out the biggest “solids” through mechanical processes.

In 2013, new federal government regulations spelled out secondary treatment – which adds bacteriological breakdown of waste – as the minimum standard required for sewage treatment. They set a deadline of December 2020.

Ken Ashley, a biologist, civil engineer and director of the BC Rivers Institute who lives in North Vancouver, thought that wasn’t good enough.

Ashley put together an option for Metro that would treat the sewage to a tertiary standard, then return the treated wastewater to local estuaries, creating habitat.

That option was rejected, primarily because of what Metro staff said at the time would be both higher capital and operating costs.

“It was not something the previous [Metro] board wanted to entertain whatsoever,” said Delta councillor and former mayor Lois Jackson, who sits on the Metro liquid waste committee and is also a former chair of Metro’s board. The reason for that was simple, she said: “Money.”

Since then, plans for a new secondary treatment plant have plodded along. In September 2018, politicians held a celebration marking the start of the project, which consisted mainly of massive piles of sand “preload” to compress the ground being moved on to the McKeen Avenue site.

For a number of people on the North Shore, however, the project has remained little cause for smiles and handshakes.

Parker, Ashley and Don Mavinic, a UBC engineering professor and world-renowned expert on wastewater treatment systems, are among them.

In contrast to coastal B.C. where “dilution as a solution to pollution” has been the norm, there are many other places where either advanced secondary or tertiary treatment have been in place for years, said Mavinic.

These include parts of Ontario, because of Great Lakes agreements with the U.S. that called for stricter minimum standards, Calgary, Portland and areas of the Okanagan.

For years, Victoria – which lacked even basic sewage treatment – was considered the environmental “villain” of the south coast. But recently, the regional government there opted to build a new $775-million tertiary treatment plant, suddenly leapfrogging over Metro Vancouver standards.

The bar had just been raised higher.

Scientific understanding of sewage also changed in recent years.

“Sewage 100 years ago was what you ate plus toilet paper,” said Ashley.

But no longer. Present in large amounts in today’s sewage wastewater are Prozac, ibuprofen, Viagra, acetaminophen, estrogen, “plus all the illegal drugs,” said Ashley.

“Sewage treatment plants weren’t designed to deal with that. They just kind of sail through the sewage treatment plant and end up in the receiving environment. It’s not your grandmother’s sewage.”

Recent studies have shown those chemicals and pharmaceuticals – the most common ones are anti-depressants – present in local waters and in juvenile salmon, said Ashley.

They also bio-accumulate through the food chain, ending up in worrying concentrations in species like the southern resident killer whales. “They are swimming around in Puget Sound and Georgia Strait close to the outfalls,” said Ashley.

Recent research, however, has shown plants that treat sewage to a tertiary level – involving both more biological processes and more filtration – also succeed in filtering out those harmful chemicals.

“Sixty to 70 per cent of those chemicals are actually removed,” said Mavinic. “They do not show up in the effluent stream.”

Early on in their lobbying efforts, Parker said he learned an important lesson when he was told by a local politician, “This was not a high priority for Metro because the public wasn’t concerned about it.”

When they began to make presentations to community groups and business leaders, the response was one of shock, he said. Most people told him, “We thought Vancouver was treating its sewage in a world-class way.”

Since then, both the public and political sentiments have shifted.

Coun. Lisa Muri, who represents the District of North Vancouver at the board, has been one of the political voices urging colleagues to take a second look at tertiary treatment.

Adding to the backdrop is a widespread belief the federal government will likely introduce more stringent rules for sewage treatment before too long. “How stupid would it be to build a plant and have it out of date before it even opened?” said Ashley.

In December, the Squamish Nation added another element when it sent a letter stating it would look favourably on granting an extension to the deadline by which Metro must move the existing plant from Squamish Nation land – if the new plant is upgraded to a higher level of treatment.

“We would like tertiary treatment or the best available technology,” said Squamish Coun. Chris Lewis.

Since Acciona parted ways with its geotechnical engineering consultants in February – prompting a $20-million lawsuit from Tetra Tech in response – and a stop work order was placed on the site at the beginning of April, work has remained halted.

In response to questions from the North Shore News, Acciona sent an emailed statement, saying, “We are continuing to work closely with Metro Vancouver and the District of North Vancouver to move the project forward.”

Metro Vancouver would also only provide an emailed statement in response to requests for a status update on the project, saying, "Metro Vancouver, Acciona and the District of North Vancouver are working together to resolve outstanding issues."

In terms of what happens next, money remains a key consideration – both in terms of capital and operating costs. But in May, North Vancouver MP and Fisheries Minister Jonathan Wilkinson and Burnaby North Seymour MP Terry Beech wrote to the Metro board, hinting strongly that more federal dollars would accompany a reconsideration of tertiary treatment.

“We’re building a piece of infrastructure that’s going to last between 50 and 75 years,” said Wilkinson in an interview. “We should be thinking very clearly about long-term environmental implications of decisions we are making today.”

Ashley credits Mavinic with some heavy lifting in pushing politicians towards tertiary treatment.

“When he says ‘This is the way it is,’ people realize they aren’t being BS’d,” he said. “You’ve got a world expert sitting there. It’s pretty handy having him in our backyard.”

He also credits Parker’s tenacity. “Glen was like a dog with a bone in his mouth,” he said. “He just wouldn’t let go. It was very hard for the politicians on the North Shore to ignore this issue.”

How much the move to tertiary will cost remains a topic of debate.

The current budget for the secondary treatment plant is sitting at about $778 million. Mavinic said going to tertiary could add between 20 to 35 per cent to that capital cost – but some of that cost could be recovered in operational savings.

“I went and talked to some of the senior consultants who are in this business. I said ‘Give me your number,’” he said. Most put added costs at between $150 million and $200 million, he said.

While neither Ottawa nor Victoria have committed more funding, Wilkinson points out that both governments ponied up cash – to the tune of $459 million between them – to get the Victoria sewage plant plans up to tertiary. “We’re certainly open to the conversation about enhancing the level of funding for this plant if they go tertiary,” he said of the North Shore plant.

“From an environmental perspective it would be a shame for us to build something to a bare minimum that we know people are moving beyond,” he said. “I do think we need to be thinking seriously.”