Hue: A Matter of Colour. Directed by Vic Sarin (Canada, 2013) World Premiere at Vancity Theatre, Friday, Oct. 11 at 10 a.m. as part of the Vancouver International Film Festival. For more information visit viff. org/festival.

Sweat streams down the child's face but he resists the urge to take off his hat or roll up his long sleeves.

He would rather be uncomfortable than dark.

Both far-reaching and deeply personal, Hue: A Matter of Colour begins with filmmaker Vic Sarin's memories of his mother steering him out of the sun and into the shade.

Both Sarin and his mother accepted that dark skin is bad, but neither seemed to understand why.

The documentary takes us from a Tanzanian compound built to ensure the safety of hunted albino children to the skin whitening industry of the Philippines. In each country and in each story, the focus is colour - not race.

The notion of prejudice based on colour within a racial group has been with Sarin since his childhood, but it's not something he was eager to put on film.

"I thought: 'Who would be interested in a subject like that? People are tired of all the social issues all the time,'" he says, speaking in a pleasant grandfatherly tremble.

The subject became more pressing as Sarin thought about colourism's role in his own life.

"You look back and you ask yourself; 'Well, how did that affect me? On what level did that affect me?' So for that you need time and history behind you."

Sarin speaks candidly in the film about the dissolution of his first marriage and his strained relationship with his oldest child.

His second wife, who is Caucasian, talks about the distance between Sarin and his family.

"I've always felt like an outsider," Sarin says.

The sensation of being trapped in the wrong skin is tactfully examined in the movie through a conversation with Filipina cosmetician Elvie Pineda.

Pineda has built an empire on the premise Filipinas want to be white.

She could easily be cast as an opportunist peddling bleaches to the insecure and self-loathing if she wasn't her own best customer.

The entrepreneur quakes with emotion as she recalls being bullied and threats of rape. It was her brown skin that made her a target, she says.

"One of these days - I'll be white!" she recalls thinking.

Both Pineda and her daughter - who refers to herself as a "walking advertisement" for her mother's business - offer very intriguing comments, but in one of the movie's saddest moments the words are inconsequential.

One of Pineda's customers agrees to be filmed while she undergoes the skin whitening procedure.

Sarin records her as she gets her first look at her pale skin.

The procedure is a success, but the patient's enthusiasm vanishes when she looks into the mirror.

She seems wounded, and when Sarin asks her if it's time to celebrate, she avoids answering directly.

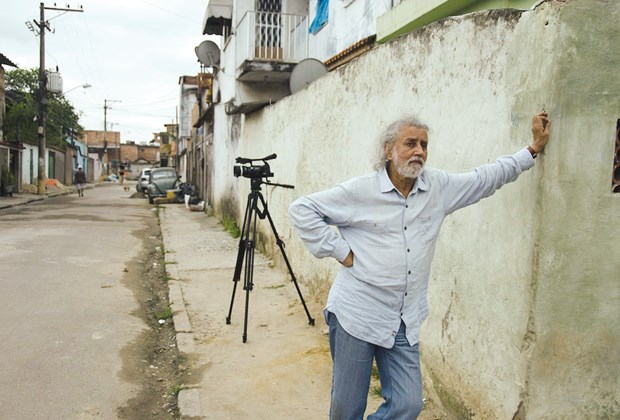

Sarin shows a great skill in getting his subjects to reveal themselves on camera.

"Because I'm an older person now, I have grey hair now, people respond differently," he says. "Once they had a trust with you, they wanted themselves to open up because they had been keeping this inside also for a very, very long time and they just wanted an outlet."

A 32-year-old Indian actress discusses her dark skin and its affect on her marriage prospects. Uttering a melancholy laugh, she talks about a one-legged man whose mother thought he could do better than to end up with a dark-skinned wife.

"I also found the women were much more easy to deal with in that direction," Sarin says. "They are far more open than men. Men. .. are much more into analyzing it and women are much more on an emotional level, human level to talk. So I think it was a good balance."

The movie intrigues us by suggesting colourism's roots preceded colonialism, but moves on without exploring the subject in detail.

"Right from the beginning of time, the colour of goddesses was white," says an Indian craftsman as he applies ivory paint to a deity's face.

"This film is not about us versus them. It's about us versus us," Sarin says. "A lot of people of my ethnic background. .. often they have been pointing fingers at others, which are mostly Caucasians, and colonization and all that stuff. It's very easy to point fingers at the other side but they never look at themselves and their own behaviour. And that to me is very important. Before you say to someone else to clean their house you should take a look at your own house."

While people will openly discuss height or weight, colour is often off-limits in polite conversation.

"We have become so politically tight that we cannot breathe even sometimes," Sarin says. "The physical chemistry will always be there."

Sarin had briefly considered narrowing his focus to Canada and India, but ultimately decided the subject was too big to be narrowed.

"This touches almost three-quarters of the world population, I can't just go to where I was born and here. No, it's much bigger than that," he says.

Sarin says he knew nothing of the Philippines or Africa prior to making the documentary, but that only added to the story's appeal.

"This is what I love about documentaries is that you go and you discover.. .. If you already know what's there, I don't want to do those films," he says. "Each time, each path takes you someplace and magic happens."