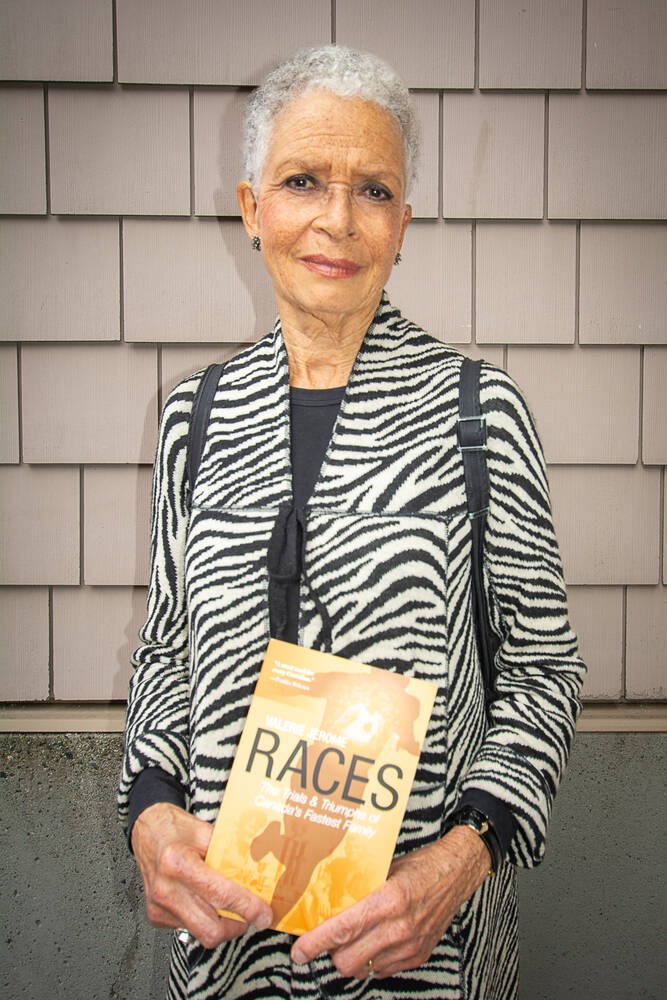

Since her revelatory new book Races released last September, Valerie Jerome has received more than a hundred emails from friends and acquaintances expressing shock at the racism her family faced.

Some were people from North Vancouver, where she and her older brother, the legendary sprinter Harry Jerome, began their storied athletic careers in high school.

One of the notes was sent by Bruce Kidd, a distance runner and darling of the Canadian athletic community in the 1960s.

“He knew Harry quite well, but he did not know that we endured any racism at all,” Valerie said. “And this is a guy that traveled a lot with Harry.”

But while Harry set seven world records over the course of his career, and represented Canada at many world sporting events, including three Olympic Games, never once was he named Athlete of the Year by the Canadian Press. Meanwhile, Kidd won the honour twice, despite mixed results in competition.

People also wrote to Valerie expressing their ignorance of the racism the Jeromes faced living in North Van. In 1951, the family moved to Lower Lonsdale because of the community’s lack of land covenants restricting certain races, but neighbours on their block still petitioned against them living there.

On their first day of school at Ridgeway Elementary, Valerie and her siblings were met by a mob of children who threw stones and shouted the worst of racist words at them.

More than 70 years later, and I can still see them. I hear their hateful cries and feel the rocks that hit the back of my head and neck….

It was the first day of school. We didn’t even make it onto the grounds.

It’s people’s lack of knowledge that was a driving force for Valerie to write the book. A lot of people are unaware, or unwilling to admit, the racism that Black people have faced in Canada, she said.

“People really do need to know their history, just as the German people have fought hard to know their history,” she said. “As painful as it is, they need to know what they have done. Maybe it’ll prevent it from happening gain.”

Jerome family faced hardship in public life and at home

Much of Races highlights the unfair treatment Harry faced as a star athlete. As his profile grew, the press would take shots at his character and race when he didn’t live up to expectations.

Such was the case during the 1960 Olympics in Rome, when Harry tore his hamstring in the 100 metre semi-final after leading the pack in his heats.

The athletes who came to speak with us were sympathetic and supportive, but vicious rumours were already circulating.

“Some Canadian officials who refuse to be named insisted that Harry could have finished the race,” Dick Beddoes of the Vancouver Sun reported. “One said, ‘His injury was 99 percent mental and one percent physical.’”

Valerie said watching the recent docuseries on David Beckham – which retells the intense public shaming the soccer player received after England’s 1998 loss to Argentina – stirred memories of how Harry was treated.

“You can imagine how much worse it was for Harry being brown, black – it’s much, much worse. It’s expected of you [to perform],” she said.

In tandem with the trials the Jerome family faced in public, Races also delves into the horrible treatment the Jerome siblings faced at home by the hand of their abusive mother.

Valerie explained that the seed of her mother’s unhappiness likely stemmed from a denial of her own ethnicity.

My mother always told us that she was White, and we never questioned her. We wouldn’t have dared.

It wasn’t until later in life that Valerie learned of her maternal grandfather, John Armstrong Howard, a Black man and Canada’s fastest runner in his day. Valerie’s mother never spoke of him.

One of the ways her unhappiness manifested was the intense physical and emotional abuse she inflicted on her children, which Valerie believes to have caused the head trauma that plagued her brothers and eventually took their lives.

Book has an unlikely hero

Like many great stories, the hero in Races is an unlikely one.

Despite her older brother’s outstanding achievements in the face of adversity, Valerie said the true hero of her book is her younger brother, Barton.

Deemed mentally slow as a child, Barton spent much of his life institutionalized.

He never raced. He never quite learned to read, as was his lifelong dream. But despite years of mistreatment and frustration, Barton remained patient and kind.

“He wasn’t treated well at home. He wasn’t treated well in school. He was totally abused in institutions,” Valerie said. “He was kind and generous, but people see a medal winner.

“I worshipped Harry, so don’t get me wrong. Harry saved my life. But Barton didn’t even have the love of his family. To me, he’s a very valuable lesson,” she said.

It wasn’t until late in Harry’s life, after experiencing seizures himself, that he was finally able to embrace his younger brother.

“He intellectually embraced Barton – sent him a million postcards over the years – but he just didn’t know how to put his arm around him or take him into his home,” Valerie said.

Over the Christmas holiday in 1981, Barton visited his siblings in Vancouver. For the first time, Harry suggested that Barton come stay with him for a few days.

Two days later at his favourite restaurant, China Kitchen, Barton barely paid attention to his food.

He was coiled in a perpetual state of readiness, eager to leave the restaurant and begin a journey he’d long dreamed of. I was nearly weeping as (my son) Stuart and I watched him heading along Granville Street, his suitcase clutched in his hand…. Barton seemed ten feet in the air.

It was the brothers’ last meeting before Harry’s death the following year.

Barton never saw Harry again, and that Christmas remains one of my most cherished memories of my two brothers.

Upcoming events

Valerie has several upcoming events for Races, which include receiving an award from the American Track and Field Writers Association on June 29 at the U.S. Olympic Trials in Eugene, Oregon.

She’s also visiting schools, with a talk at Ridgeway Elementary on Sept. 18.

Valerie will present at the Word Vancouver Reading & Writing Festival Sept. 21, and at the Whistler Writers Festival Oct. 17 to 19.