Haida Modern, Directed by Charles Wilkinson. World premiere at Vancouver International Film Festival, Oct. 1, 6:30 p.m. at Vancouver Playhouse (viff.org/Online/f37332-haida-modern).

By the late 1960s, the Haida totem poles that had been spared the axes of missionaries, ethnologists and thieves stood like pillars of a lost city.

And when those old ones fell, pieces of a culture would topple with them.

If we measure time by living memories, the act of raising a totem pole had been relegated to the distant past when artist Robert Davidson was in his early 20s.

In the new documentary Haida Modern, Davidson recalls wandering the Museum of Anthropology at UBC as a young man and seeing the art his ancestors created. But when he returned to Haida Gwaii, he recalls, there was almost nothing.

“I felt there was an emptiness,” he says.

Shortly afterward, Davidson and his brother Reg began carving what would become the first new totem pole in a century.

But in unearthing the art of the past, some community members worried the brothers were also dredging up the pain buried back there.

There was a fear that white people would throw them in jail, elder Sphenia Jones says. Reg remembers neighbours who worried the totem pole would ruin their chances of getting into Heaven.

The film shows a black and white photo of eight smiling nuns standing outside a residential school, flanking a group of Indigenous children who are each wearing a cartoonish version of a feathered headdress. Among the 10 children, there’s not a single smile.

Jones remembers being whipped. She remembers the children being told they didn’t know how to worship God.

“I couldn’t understand why there was a god like that,” she says in the film.

Davidson’s own father was sent to Coqualeetza Indian Residential School in Chilliwack, which became notorious following the discovery of unmarked graves nearby.

For Davidson, the totem pole was about giving people something to celebrate.

In the summer of 1969, the pole was raised.

The culture, to use Davidson’s word, was “awoken.”

“I had no idea how important it was.”

Now in his 70s, Davidson is continuing to carve, create and captivate.

Documentary film producer and editor Tina Schliessler remembers seeing Davidson 40 years ago when her father was making a documentary about Reid.

“I thought he was amazing,” she says.

“His story is a really wonderful story to tell,” agrees director Charles Wilkinson.

Wilkinson has a background as a dramatic filmmaker. “Which means I’m a real pushy, manipulative guy,” Wilkinson offers with a laugh, noting his habit of coaching, prodding and questioning performers.

But with Davidson, “You wouldn’t dream of pushing him around.”

In telling his stories, Davidson manages to display equal doses of humour and tranquility.

“Honestly, Robert makes Perry Como look like a bundle of nerves,” Wilkinson says.

Over the course of the film Davidson tells stories about his parents, about playing cowboys and Indians (he was always a cowboy) about kindness, friends on skid row, and about living in two cultures.

His stories are underscored by lingering shots of wildlife – at least one of which came at great personal risk to the filmmakers.

Wilkinson and Schliessler were shooting footage in the woods when a grizzly bear lumbered into view.

Wilkinson continued shooting, confident his colleague had bear spray at the ready.

“I look over . . . and Tina’s not manning the bear spray, she’s filming too,” Wilkinson says. “But I can see she’s getting really cool footage; possibly cooler than me.”

After a brief exchange, Schliessler handed over the spray and kept shooting. Wilkinson, not wanting to be outdone, put the bear spray on the ground and resumed filming.

“Tina looked at me and just went, ‘Are you insane? What’s wrong with you?’” he recalls wistfully. “But we got some spectacular footage of that bear.”

Haida Modern Trailer from Charles Wilkinson on Vimeo.

Once filming concluded, Wilkinson and Schliessler headed back to the North Shore to comb through hours of stories, observations, and introspection.

The next seven months were full of “Long days, just staring at the screen and trying to understand what the thread of the story is,” Wilkinson says.

Eventually, they weaved together the story of Davidson’s life as well as his position among great artists while incorporating interviews with his children in addition to activists, artists, historians and art historians.

The film is a tribute to art, nature, and possibility of true reconciliation, Wilkinson notes.

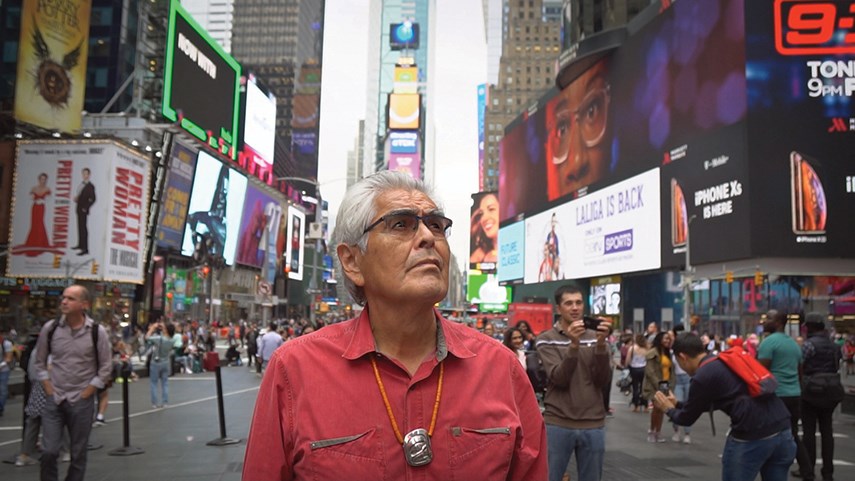

After trailing Davidson to New York and back, the hardest part for Schliessler, was the decision to stop filming, she says.

“You could follow him,” she begins.

“Forever,” Wilkinson finishes.