“Not long after the first smallpox epidemic all but decimated the Tsleil-Waututh people, the Squamish people came down from their river homes where the snow fell deep all winter to establish a permanent home at False Creek. Chief George – Chipkayim [Chepxim] – built the big Longhouse. Khahtsahlano was a young man then. His son, Khahtsahlano was born there. Khahtsahlano grew up and married Swanamia there. Their children were born there ...” – Lee Maracle: “Goodbye Snauq”

Chief George Chepxim Siy̓ám̓ and his people from the upriver Squamish village of Ch’éḵch’eḵts established a permanent village around 1860. – senakw.com/pdf/Senakw-Lands-Presentation.pdf

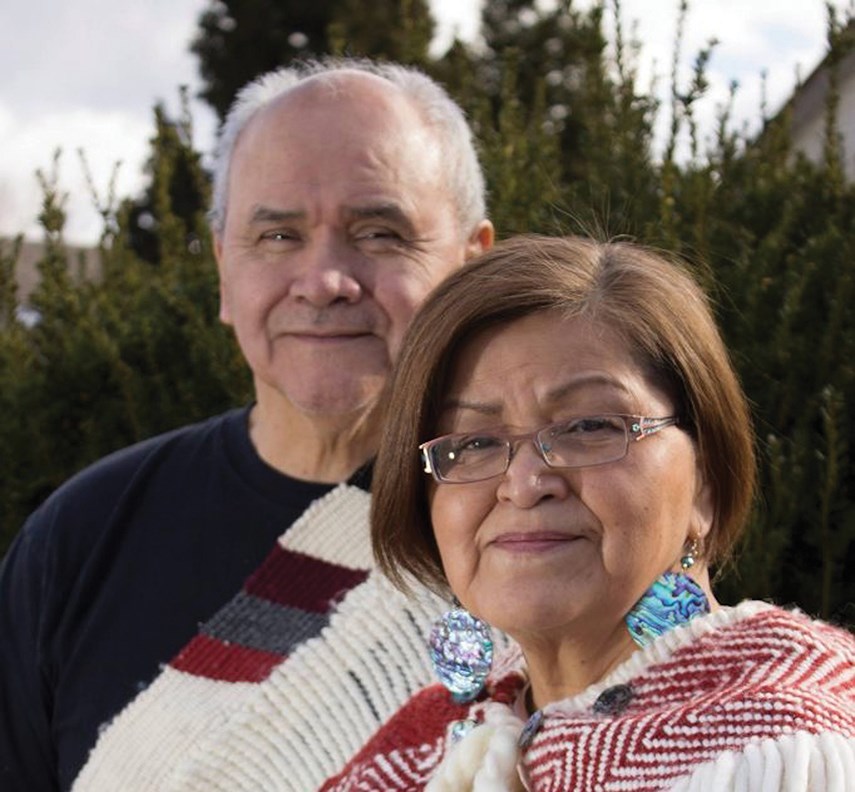

Squamish Nation master weavers Skwetsimeltxw Willard ‘Buddy’ Joseph and Chepximiya Siyam’ Chief Janice George have left their Blue Cabin Artist Residency at False Creek during the COVID-19 crisis but once they’ve settled back into their home on the North Shore of Burrard Inlet they intend to continue their project of replicating a rare 18th century Coast Salish ceremonial robe.

“It’s understandable,” says George. "We had to leave but we enjoyed our time there. We are very grateful to be included in the Blue Cabin project. It was beautiful living where my ancestor was the chief, the chieftainship that I carry. It was a great honour.”

George comes from a long line of Squamish Nation master weavers, and with Joseph, has helped to revitalize the lost Coast Salish textile art form over the past two decades.

“We learned (from Susan Pavel and Subiyay-t Bruce Miller of Skokomish in 2003) and started teaching in 2004. With all the people that we’ve taught, and we ask people to be teachers as well, over 3,000 people have tried [Coast Salish weaving]. Not all people are weavers but we’re teaching the techniques and also the teachings that go with it – that’s an important part, as well, the teachings of our ancestors and elders.”

George’s grandmother Kwitelut-t Lena Jacobs, born in 1910, as well as her mother and grandmother, were all weavers, and their teachings were passed down through generations.

“We like everyone to try weaving,” says George. “And to learn some of the teachings that go with it. We teach in schools, from K4 all the way up to university. The teachings relate to how we feel about everything, our worldview.”

The ceremonial robe the Squamish Nation weavers are replicating was made in what is called the Classic Period of Coast Salish weaving, before European contact and the introduction of Hudson’s Bay blankets to the West Coast.

No one knows the name of the woman who made the original robe, or where she was from, but from what we know now it could only have been produced somewhere in the Coast Salish world – Burrard Inlet, Vancouver Island, Squamish Valley, Fraser River or down in Washington State – all were part of the distinctive weaving culture capable of making the robe, which is so much more than just a robe.

“The style on the spindle whorls is associated, on the rattles and on the masks and perhaps too on the grave monuments, with the power of the ritual word as used in purification. Ritual words may have played a part in the spinning and weaving processes, for example, the spinner may have recited them to the wool or to the spindle ... There may, however, be a more direct association between spinning and purification. Mountain goat wool, one of the substances spun though not the only one, seems to be itself associated with purification; it appears on the ritualist’s rattle and on costumes worn by persons undergoing crisis rites, for example, the “new dancer” at the winter dance. It is white, like the feathers and down of the sxwayxwey. And it is the stuff of blankets, which are given out when the purifying rattles and masks are used. (Laura Greenberg and Marjorie Halpin have suggested to me that a structuralist analysis would show a parallel between the rattle and the spindle whorl: both are involved in transformations, the rattle in the transforming of human beings from one state into another, the spindle whorl in the transforming of wool into wealth).

– Wayne Suttles, “Productivity and its Constraints: A Coast Salish Case,” Coast Salish Essays (Talonbooks, 1987)

“These robes were probably the most valuable items of Salish material culture. Because it took many highly skilled carvers, spinners, dyers, and weavers years to make a single cloak, they were rare. Robes were made to be evocative and transformative. The owner of a robe gained status as well as social and spiritual power.” – Katharine Dickerson, “Classic Salish Twined Robes ,” B.C. Studies, 2016)

The Coast Salish ceremonial robe, George and Joseph are replicating, is housed in the National Museum of Finland, and is the oldest object in the Museum of Cultures section (which now has more than 40,000 artifacts in the collection). It was catalogued in 1828 with the designation VK-1 as “an overcoat worn by Indians from California.” 150 years later, Paula Gustafson, while doing research for her seminal study, Salish Weaving, (published by Douglas & McIntyre in 1980), identified the item in the Finnish collection as a Coast Salish robe from what she defined as the Classic Period (1778 to 1850), when there was little outside influence on the Indigenous textile industry. Only three Classic robes (in museum collections in Finland, Scotland and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.) and the fragment of a fourth (also in the Smithsonian), are known to exist.

Of VK-1, Gustafson wrote, “The blanket in Finland, is without question, a prime example of the finest in Salish weaving. It was received by the Helsinki University in 1828, just a year after the first Finnish university had burned, destroying all the national museum treasures. It was traditional for items of public interest to be donated to the museum, and the blanket was a particularly generous contribution to the new collection by Anders Gustav Grenqvist, who was then a translator for the Finnish military at Suomenlinna Fortress in Helsinki. How the blanket came to be in the possession of Grenqvist is not known, but it may well have been passed to him by a member of one of the Russian exploration expeditions that visited the Pacific Northwest coast during the late 1700s.”

Grenqvist, stationed at the Suomenlinna Fortress, donated the robe to the Coin, Medals and Art Cabinet department of what was then called the Imperial Alexander University. “At the time, Finland was a Grand Duchy of the Russian Empire, and Finns were also in service in the Russian Navy,” says Pilvi Vainonen, curator of the National Museum of Finland / Suomen kansallismuseo, in an email to the North Shore News.

In the 18th century the focus of the Russian fur trade switched from sable to sea otter, from Europe to China, and from the land to the sea. Sea otters came into the picture for the Russians when they started exploring the Kamchatka Peninsula and further south along the Pacific Northwest coast. Their expansive imperial ambitions eventually led them to build Fort Ross in what is now Sonoma County, California, the southern-most reach of the Emperor’s Russian-American Company.

No European sources have ever placed the Russian-American Company in Coast Salish territory but Chief Joe Capilano told Pauline Johnson about a Russian ship that once visited Howe Sound when he met her in London during his trip to meet King Edward VII in 1906. Johnson included the tale in her 1911 compilation, Legends of Vancouver, based on stories told to her by Capilano and his wife Lixwelut Mary Capilano.

A Russian ship would have been a rare sight in waters already contested by English and Spanish interests but the robe could have been obtained anywhere in the Coast Salish area or from someone who had traded with Coast Salish. The garment may have even made its way down to California before arriving at its final destination in northern Europe. Although ‘California’ was as abstract a notion as ‘Nootka’ and its actual origins are lost in the mists of time.

Grenqvist described his gift to the Finnish museum in 1828 as “an overcoat used by the savages...” Gustafson says in Salish Weaving, “It might be better described as a weaving representing great wealth and prestige to its original [Coast] Salish owner, and it probably cost the Finn or Russian purchaser a small fortune in trade goods. Three things are remarkable about the blanket: the masterful use of small patterns to create a unified and visually interesting design, the excellent colour balance of yellow/black, red/blue and natural white, and the fact that it is so finely woven. The warp count is 21 to 23 warp threads per 20 centimetres (four inches). The vegetable fibre warp threads are doubled, i.e. two parallel strands are used as one. The weft fibres are unidentified, but I believe both warp and weft are composed of stinging nettle fibre.”

After Gustafson published her book, Salish Weaving, the material content of the robe was further analyzed, says Finnish curator Vainonen, passing along information about the rare item from her museum’s catalogue. “The fibres of the blanket [were] put to analysis in Canada by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police laboratory in Ottawa in 1982. According to the analysis there are no vegetable fibres but the majority of both weft and warp fibres as well as the fringes are made of mountain goat wool. In addition, there is another animal fibre, the origin of which could not be defined. According to the lab analysis, the animal fibres in the blue and pale blue yarns are similar to sheep’s wool although it is possible that there might be some dog hairs (woolly dog) present.

“The use of dog hair in weaving is based on native oral tradition as well as documented by early explorers to the Northwest Coast,” says Vainonen. “When European machine-made trade blankets were brought to the Northwest Coast, it dramatically diminished the use of dog hair and the special breed of wool dog became extinct by 1875 (according to research published by the Smithsonian, 2005 and Gustafson, 1980). The latest archeological findings seem to support the existence of a special type of dog (“woolly dog”) bred by the Salish and the use of its hair in weaving. The Smithsonian study to investigate the presence of dog hair in Coast Salish blankets is on-going but the preliminary DNA analysis seems to substantiate the claim that some Salish blankets do have dog hair.”

George's great-grandfather hunted mountain goats on Ch'ich'iyúy Elxwíkn' (The Sisters or The Lions) and she's reminded of the important role he played in the process every time she looks up at the mountain peaks.

The Squamish Nation weavers are using the twining technique and some of the twilling technique in their replication of the robe," she says. “We always tell people everybody in the world has a weaving history. The difference between ours and others is the materials we use historically and also the spiritual, cultural and traditional teachings that go with it.”

Once they’re settled, George and Joseph will get back to the loom and continue their project for the Blue Cabin Artist Residency.

Selected references:

Katharine Dickerson: “Classic Salish Twined Robes,” (B.C. Studies, 2016)

Paula Gustafson: Salish Weaving (Douglas and McIntyre, 1980)

Pauline Johnson: “A Squamish Legend of Napoleon,” Legends of Vancouver, (David Spencer, Limited, 1911)

Lee Maracle: “Goodbye Snauq,” (West Coast Line, 2008)

Museum of Anthropology: The Fabric of Our Land – Salish Weaving, UBC, 2017, (The original robe was loaned to MOA for the exhibition)

Wayne Suttles: “Productivity and its Constraints: A Coast Salish Case,” Coast Salish Essays (Talonbooks, 1987)

Leslie H. Tepper, Janice George and Willard Joseph: Salish Blankets: Robes of Protection and Transformation, Symbols of Wealth (University of Nebraska Press, 2017)