Douglas Coupland’s art installation, Vortex, opens today at the Vancouver Aquarium. Vortex is an activation by Ocean Wise to tackle the global ocean plastic pollution crisis. Learn more about its Plastic Wise initiative at ocean.org/plasticwise.

In Douglas Coupland’s new art installation, humanity finds itself in the same boat.

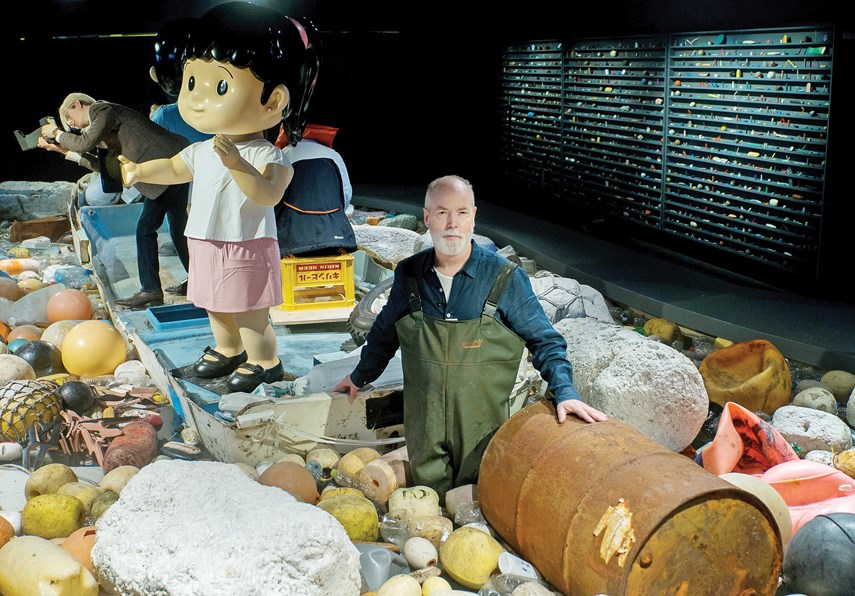

Vortex might be one of the first large-scale artistic representations of the Pacific garbage patch, giving guests the opportunity to experience a gyre of marine debris and discarded plastics – first discovered in the Pacific Ocean some decades ago and estimated to be larger than Texas – in the intimacy of the Vancouver Aquarium.

The focal point is a 50,000-litre water exhibit. A boat sits at the centre of the ocean while a cadre of characters meant to represent the past, present and future of people’s relationship with plastic lie adrift at sea surrounded by plastic garbage and the remnants of human consumption. Meanwhile, the sound of the ocean fills the room, mist rises from the water, and the unfortunate link between plastic and shoreline is ever present.

For the Generation X author and well-known visual artist, the experience of diving into environmental art was a long strange trip.

“In ’99 I was in Tokyo and I was in the Daiei department store and I was in the cleaning products aisle and it was just wall to wall beautiful candy-coloured paint,” Coupland says, describing how he purchased about 120 cans of the vivid stuff, eventually bringing them back to Vancouver to use in a sculpture project.

He was shocked, however, when the vestiges of his time in Japan showed up on B.C.’s shores. For years, Coupland explains, he had been making pilgrimages to Haida Gwaii, an archipelago he describes as “the most perfect place on Earth.” But in the summer of 2013 one of those cans he’d first encountered more than a decade prior in Japan seemed to wash up at his feet while wandering the region’s northern tip.

“It scared the shit out of me actually,” he says. “It did feel like being on the receiving end of some kind of curse.”

For the past few years, Coupland has been trying to reckon with that curse, noting that he could: “No longer just pretend this stuff is invisible.”

A synthetic model of iconic artist Andy Warhol – who once pronounced that in Hollywood: “Everybody’s plastic, but I love plastic. I want to be plastic” – can be seen holding a Polaroid camera on the boat in Vortex, representing society’s past relationship with plastic.

“(Plastic) was uncritically accepted and almost worshipped by society for a century and then that all changed in recent years,” Coupland says. “We’re now in the era of complexity.”

In Vortex, that complexity is symbolized in another model figure, hunched over next to Warhol, who’s seen wearing a life-preserver. The figure is described by Coupland as a Tunisian refugee en route to Sicily and a better life.

“She’s from a country where they have oil, but none of it goes to the people who live there and environmental degradation forces them to leave and go other places,” he says. “She’s wearing polyester plastic clothing that has no thermal capacity. She just really embodies everything that’s wrong about plastic in the modern era.”

Meanwhile, pieces of plastic that were foraged by Coupland and others during his own garbage and plastic cleanups in Haida Gwaii bob mercilessly around the boat, blotting out a clear view of the ocean.

And while the damage wrought by the Pacific garbage patch is rightly criticized, Coupland’s installation suggests that plastic can still be made an important part of everyday life, as long as the distinction between good plastics and bad plastics are known.

Bad plastics might refer to the millions of tonnes of single-use plastics that find their way into the world’s waterways every year – items such as straws, bottles, bags, and cups.

Good plastics are plastics that can work in harmony with their surroundings, such as Coupland’s Lego towers – first showcased as part of a futuristic-looking cityscape in his 2013 solo exhibition at the Vancouver Art Museum – that are repurposed and recycled for Vortex.

“Plastic’s not all bad. I think Lego embodies the best of plastic,” he says, gesturing towards the Lego towers that have been sealed behind a glass pane in a water-filled display and reimagined as an underwater reef. Small red and golden fish – called Cichlids – float through the exhibit, ducking in and out of the towers’ crevices like it was their own natural environment to begin with, a perfect marriage between art, plastic, and the aquarium’s own marine life.

Coupland, who lives in West Vancouver, is confident that people have the capacity to change their behaviour for the better, noting there was a time when people used to litter like it was no big deal until, suddenly, it was a big deal and they stopped.

“We do change. I’ve seen people change, so we can change again. We’re on that moment historically,” he says.

Asked what guests should come away with after viewing his installation and circling the scavenged boat of Vortex, he says he hopes people can rethink their relationship with the sea.

“I’ve spent my life here on the North Shore,” he muses, “and there’s never been a day where I haven’t seen the ocean.”