Anosh Irani’s Bombay Black, Firehall Arts Centre, until Dec. 15. For details visit firehallartscentre.ca.

The customers may not touch the dancer.

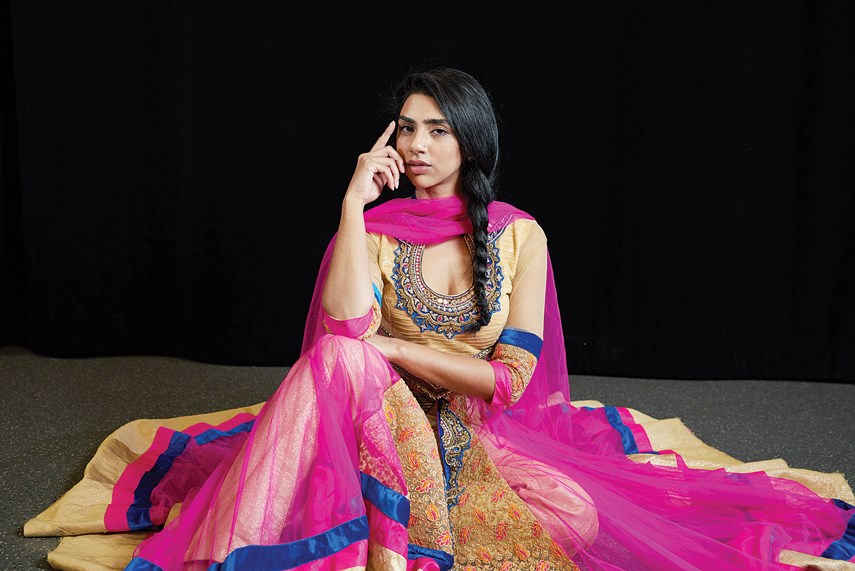

It’s a necessary rule for Aspara, the dancer at the centre of Anosh Irani’s play Bombay Black.

A steady stream of clueless, aroused men pay to be seduced by Aspara’s artistry and tartistry so of course they must be barred from pawing at the object of their infatuation.

It’s a good rule. But it seems to extend past the customers to everyone on the planet except Aspara’s exhausting mother, Padma.

Poetic, darkly funny and mythic, the play begins with Padma instructing her daughter on the finer points on using exotic dance to render the customer’s higher brain functions nonexistent.

After Aspara declines to take an evening walk with her mother and thank the sun for its service, Padma employs emotional tactics that may be recognizable to those familiar with mothers and/or guilt trips.

“If the sun doesn’t rise tomorrow, it will be your fault,” she tells her. “The whole world will be plunged into darkness because you are a selfish little bitch.”

The life of the passive-aggressive mother and her aggressively passive daughter are upended by the entrance of a blind man.

He wants to be in Aspara’s presence and perhaps, he will reveal the real reason he’s there.

Director Rohit Chokhani first staged the 2006 play for the 2017 Vancouver Fringe Festival. Chokhani is once again in the director’s seat for what Firehall Arts Centre artistic producer Donna Spencer says should be a more fully-formed version of the play.

“At the Fringe you have to get in and out in 45 minutes,” she says. “Here, it’s really got a full lighting design, a full sound score.”

Part of the aim of the Firehall is to provide a nurturing atmosphere for artists, Spencer says, explaining that instead of scraping together the cash to hire actors and rent a space, Chokhani can work with the theatre staff to ensure his “technical aspirations” for the play are realized.

“It gives them, in terms of creating the work, less to worry about,” she says.

Spencer was enthusiastic to help Chokhani bring the play to a wider audience.

The production will provide work for South Asian theatre artists, while helping Chokhani develop as a director and producer, Spencer says.

“He’s got a drive that should be encouraged,” she says. “It was one of those: ‘All right, you want to do this. We have a theatre. We’ll help you.’”

Bombay Black is replete with challenging subject matter. The drama delves into the challenges single mothers face while raising children in India, Spencer notes. The show also deals with the practice of children being: “betrothed to others before they’re even thinking about things of love,” she says.

“It is sad, but I think it’s kind of a love story, too.”

It’s also somewhat timely, she says.

“I certainly don’t believe the problems are solved in India but there certainly is an awareness of young girls being bought for dowry . . . that’s much more on the radar than it was when Anosh (Irani) first wrote the work.”

Now in her fourth decade with the Firehall, Spencer remains passionate about supporting theatre.

“I wish I could support more work,” she says. “In actual fact we can’t support a lot so we do the best we can.”

She began what she thought would be a three-year stint with the Firehall in 1981, she recalls.

“I don’t think I ever aspired to run a large organization. It was more about how theatre could impact people’s lives,” she says. “It’s always rewarding when somebody says, ‘You know, I saw a show here when I was in high school and that’s why I come now.’ And that actually has happened.”

By its intimacy and uncertainty, theatre remains distinct and valuable.

“When you go to the theatre you’re actually living the experience with the people that you’re seeing on stage,” she says. “Everyone should try it.”