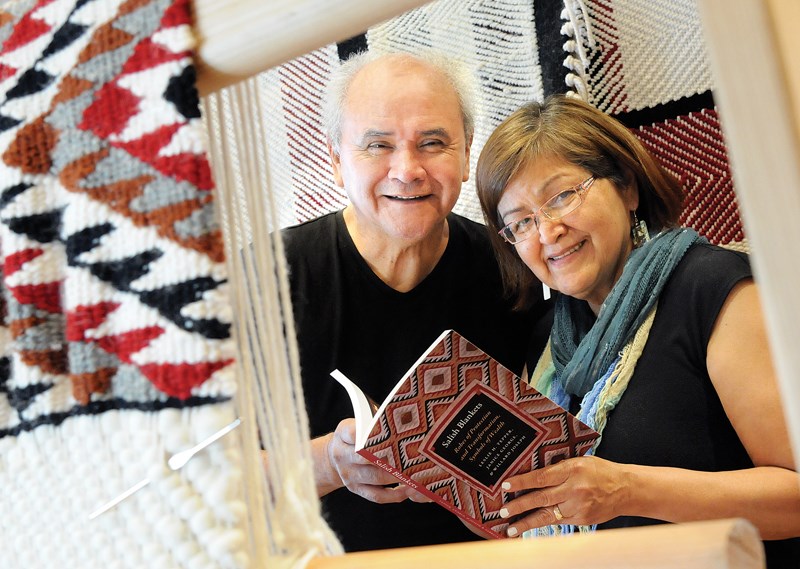

Chief Janice George and Willard “Buddy” Joseph are accomplished weavers and educators, sharing their wealth of knowledge and teachings of traditional Coast Salish weaving to those eager to learn firsthand.

And now, being published authors can be added to their list of undertakings, as part of their ongoing effort to help the practice of weaving sustain itself in the future.

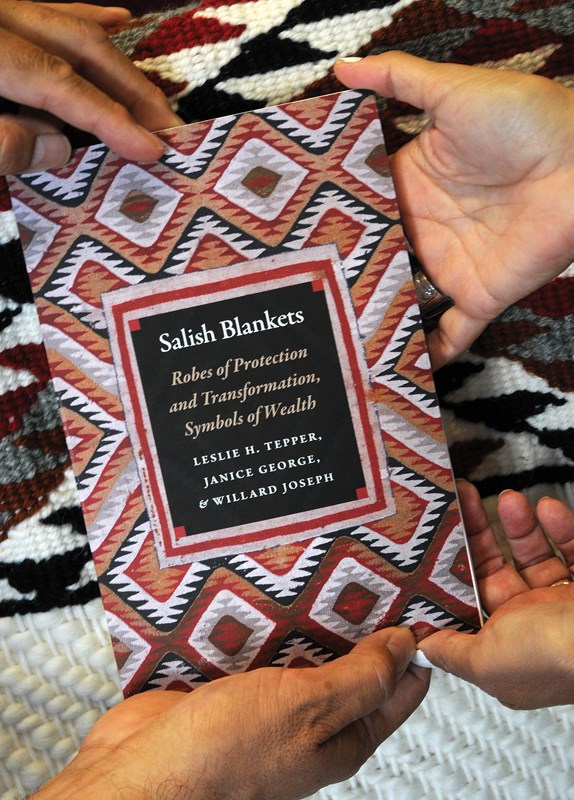

The Squamish Nation duo’s new book, Salish Blankets: Robes of Protection and Transformation, Symbols of Wealth, draws on first-person accounts from Salish community members to offer a comprehensive look at the technical skills involved in weaving. It also examines the numerous ways that weaving plays an important role in Salish and Indigenous culture, both now and historically.

“We think it’s important to keep alive because every part of the culture and the traditions are important to what we do today. We feel like the culture is the foundation of a healthy lifestyle,” says George, who is a hereditary chief of the Squamish Nation.

In 2004, George and Joseph, who are married, opened their studio called L’hen Awtxw Weaving House, after first trying their hand at weaving during the previous year.

“It was kind of the major turning point in our lives,” explains Joseph. “We travelled to Washington state to learn how to weave in October 2003.”

The legacy of weaving is described near the beginning of Salish Blankets as “one of the world’s great textile traditions.”

Although modern observers of Salish weaving may embrace it because of its esthetic qualities, weaving historically was also about practicality.

“At the time they were making their art they were adding to the community in functional ways – warmth, carrying things with baskets, and masks had a specific use as well,” George says.

But now, she adds, “we consider them art.”

Joseph is the great-great-grandson of Harriett Johnnie, a renowned weaver, and George is a graduate of both Capilano University and Santa Fe’s Institute of American Indian Arts.

The pair both come from prominent Squamish Nation families, and partake in the important cultural and ceremonial aspects of their heritage with pride.

“Being a student of art and having researched my own people, I know that it’s very significant in our culture,” George says about weaving. “It’s the foundation of our ceremonies and it’s used in many ways that are very important.”

For example, when weaving Salish blankets to be worn as ceremonial robes, a process that Joseph says can take around four months to complete, the pair is devoted to honouring the historical significance of such robes, as well as their place in contemporary First Nations society.

Wearing woven robes was – and still is – a form of transformation, a way to move a person from the everyday into the sacred.

“They are protective garments that at times of great changes in a person’s life – celebrating a birth, participating in a marriage, mourning a death – offer emotional strength,” reads a passage in the book.

Joseph says when they teach weaving techniques to their students they focus on the fundamentals of weaving, the same techniques that Salish people have been using for thousands of years.

“We really feel that weaving is one aspect of our people’s identity. I think when we’re teaching it, it is experiential for the students as well as for ourselves,” Joseph says.

But they stress that their teaching and passing on of their people’s weaving legacy isn’t solely for the younger generation to carry on.

Canada’s residential school system and history of Indigenous oppression led to many Salish people, even elders, being robbed of the opportunity to practise weaving, they say.

George describes being able to teach her own aunt the techniques involved in weaving, and highlights the satisfaction it brought both of them.

“We’ve been able to teach elders as well that weren’t able to learn. That was very emotional. That was very emotional for them and very emotional for us,” she says.

George and Joseph hope their new book can provide a permanent, living testament to the cultural practice and art form of weaving. The book meticulously examines the history of the different materials, styles and locations of this Salish textile tradition, which is an important thing to record for future generations, they say, because so much of Indigenous history was based on solely oral traditions.

Many of these traditions, however, lost ground – or were lost completely – through the unfortunate legacy of Canada’s oppression towards its Indigenous populations.

And while George and Joseph teach and write about weaving so that future generations can benefit from it later on, the satisfaction they get from it now is something they’re making sure to cherish.

“To see our youth wanting to weave and learning about it, I feel like it will go into the future for generations to come,” says George. “For me, that means the world.”