The act of having fun raises levels of dopamine, endorphins, and oxygen in a person's body: all essential ingredients for learning.

For educational games to be successful, their creators have to be meticulous about striking a careful balance between education and entertainment. Best Universities compiled a list of how different types of digital games meant for teaching students have evolved over time, ranging from DOS games like Oregon Trail to the latest version of the Scratch programming app for kids.

Twenty years ago, children took computer science classes in school with specific units for programming, typing, and other concepts. Today, students learn these same concepts from playing Minecraft, making their own servers for games, creating and installing "mods" that change the gameplay experience, and learning old-school HTML to create '90s flashback looks on their itch.io pages.

But with any discussion of video games comes the debate around screen time, which has long been a point of contention between parents and children. While educational games served as a compromise, the pandemic pushed most parents to concede screen time for online learning. And without a physical classroom, many educators seized the opportunity to use video games in unconventional ways to teach history, science, and coding during the height of pandemic-induced distance learning.

The world of educational video games has a rich, decades-long history. These games directly tie with analog educational technologies like creative worksheets, classroom role-playing projects, and even educational vinyl albums from previous decades. Developers are constantly iterating to make the latest technology more educational.

The Washington Post // Getty Images

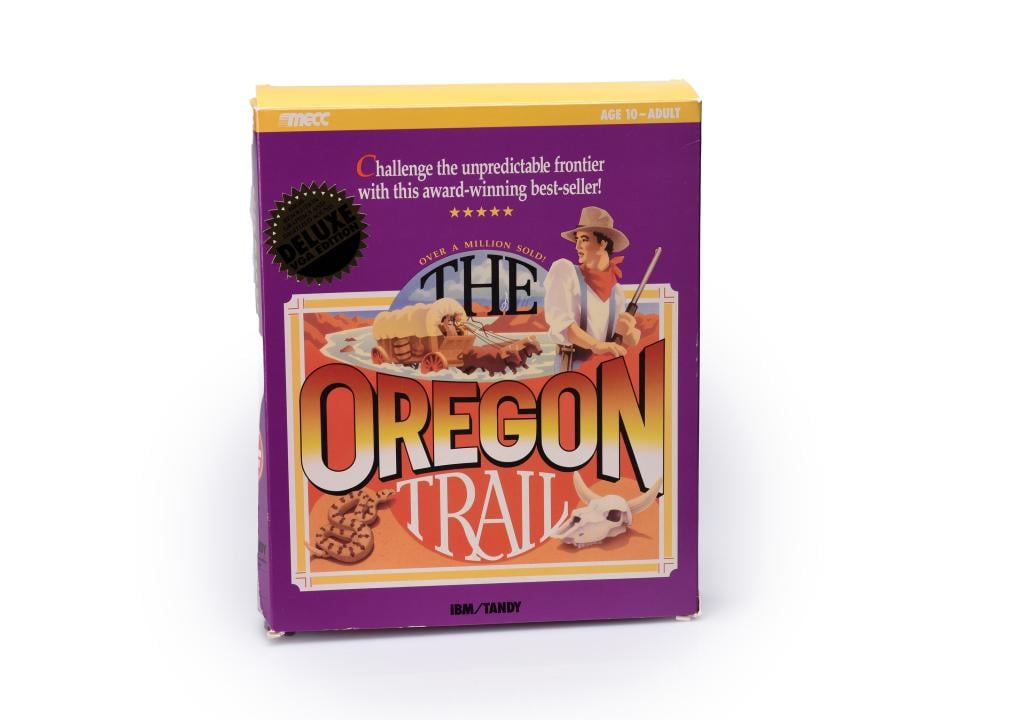

The Oregon Trail and DOS games

Before the first Windows operating system brought graphical user interfaces to most computer users, there was the disk operating system, or DOS. This text-based software worked via users inserting floppy disks into computers and running them directly using typed-in command prompts. Text was easy for early home computers to parse, which sparked the creation of text-based games.

The Oregon Trail was first developed in the 1970s as an all-text game: a way for students to interact with and learn about the journey white settlers took along the historic wagon route to the West. In the 1980s, the game received a major facelift when it was adapted into a full game with graphics that left it with the iconic look we still remember today.

San Francisco Chronicle/Hearst Newspapers // Getty Images

CD-ROMs for summer learning on PCs

The late 1980s ushered in the CD-ROM era, which trickled out to home computer users over the next decade. These read-only discs had significantly more storage than floppy disks, supporting 500 megabytes or more instead of just 1.44 megabytes on a 3.5-inch floppy disk.

Users were accustomed to needing up to 10 or more floppy disks to install DOS software like WordPerfect, but now, just one CD-ROM was all that was needed to run new games full of cutting-edge graphics and animations. This ushered in a golden age of educational CD-ROM games in the 1990s, with iconic brands like Math Blaster and Reader Rabbit helping students prep for class time.

Mark Boster // Getty Images

Interactive digital worlds

Early proto-social networks emerged in the 1990s, along with the proliferation of CD-ROM games, such as the girl games website Purple Moon. Purple Moon linked social educational games with early sponsored content from relevant brands.

These games, starting with sites like gURL and extending through massive, multiplayer online games like Neopets and Club Penguin in the 2000s, offered at least partially safe spaces for kids to play games and improve skills like hand-eye coordination and typing. These sites sometimes didn't have enough moderators and fell victim to trolling, brigading, and hacking: a classic problem experienced as the internet grew.

The Washington Post // Getty Images

Handheld gaming devices

Popular home gaming consoles gained popularity with the family-friendly Nintendo and Super Nintendo in the 1980s. When it was released in 1989, the Game Boy immediately changed how games could be carried around. A wave of ersatz children's handheld video game devices followed.

These included single-game Tiger handhelds and educational "children's computers" like LeapFrog, the first-ever proto tablet designed for children to be portable and durable. Sesame Street, Jump Start, and other licensed children's properties led the way in educational games for little kids, while games like Minecraft have made their way to the extremely popular Nintendo Switch system.

Today, kids can even use smartphone apps to learn to code.

Andy Cross // Getty Images

Typing games

Mavis Beacon is among the most iconic typing software in history, published continuously since 1987, even as technology continues to evolve. But typing in schools dates back to the typewriter days of the 1950s and 1960s—especially for young women.

In the 1990s, companies made software specifically for schools and at special group rates. There are more "fun" typing games made for very young kids, while older children may have more businesslike software. There are also plenty of regular games that use typing as the mechanic.

MediaNews Group/Reading Eagle // Getty Images

Lessons in coding

Early coding languages were very specific and text-only, with obtuse jargon that was often a necessity for code to fit into the space available. But as computers became more powerful, coding evolved as well. This reflects a movement among computer scientists toward programming languages that use whole words, for example, or visual "blocks" of code that click into place together.

The MIT-created programming language Scratch lets people of all ages make "interactive stories" on almost any device using the official app. In Minecraft, people "program" using specialized blocks in sequence. And in schools, teachers can use modified environments for languages like Python and Java to teach coding the old-fashioned way.

TOBIAS SCHWARZ // Getty Images

Virtual and augmented reality

Educators can use virtual and augmented reality technologies to help engage people of all ages in innovative ways. Established entities like museums can turn their collections into virtual galleries, allowing remote "visitors" to experience artwork, science displays, and more. On-site, these museums can use AR to transform the traditional "guided tour" into a more immersive experience.

Adding game-like elements to virtual reality or augmented reality experiences, like item collection and achievements, may help students retain the information better. These same ideas have transformed everyday life into richer educational opportunities, such as prison abolitionist Mariame Kaba's walking history called Slavery and Resistance in NYC (1626-1865).

This story originally appeared on Best Universities and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.